Hear Friedheim play Liszt’s Feux follets, recorded on disc in 1912.

Feux follets

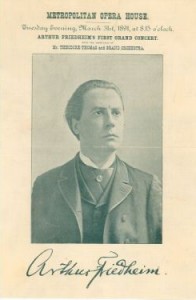

The more one reads descriptions of Liszt’s playing, the more one becomes curious to hear the unhearable. Even if Liszt had obliged with a souvenir during his old age, how could it possibly reflect the fiery playing of his virtuoso years, the pianism and compositional growth which activated many directions in Nineteenth-Century music? Taken together, those disciples and piano students of Liszt’s who made recordings left a composite portrait which still remains a mosaic: Sauer drew on Liszt’s inspiration, Siloti transformed his contact into an expanding mystical experience. Arthur Friedheim is unique among all Liszt’s pupils for the dignity and understanding with which he accepted the role as Liszt’s prophet, striving to spread the aesthetic, style and visionary quality of the composer whom he served as secretary, pupil and amaneunsis for nearly six years.

Such a role easily leads to exaggeration: in fact during Friedheim’s youth he was chided for copying Liszt’s mannerisms. By the time he recorded, Friedheim had passed into a stage marked by a mature interpretive style. What is most fascinating is his projecting Liszt in a classic, Apollonian manner, seeking to remind all of Liszt’s legitime right to a realm within music’s pantheon. Improvements in restoration have exposed more layers of detail on his primitively recorded discs, leaving the surprising impression of an interpretive style very close to Busoni’s. Busoni infused every work with his sardonic, Mephistophelian world view, supported by a transcendent technique. Like Busoni, Friedheim was a technical wizard: while Liszt’s Feux Follets is taken at an electrifying tempo, the bold architectonic delineating of the phrases, long line and their natural flow masks digital feats which pass by innocuously. His beautiful tone infuses each note, even rapid scale passages which become washes of warmth and color. The Chopin Scherzo indicates a hyper-sensitivity to tone and mastery of its projection. Friedheim stand far apart from the indulgent taste for witty grotesquery which Busoni’s de-constructing utilized as a critical element, a running commentary on music while executing it. Differences aside, it was Friedheim who furthered Busoni’s comprehension of Liszt. Dent writes:

” He gave him useful suggestions about certain works of Liszt which he had often heard Liszt play, and pleased Busoni by telling him that he had ‘arrived’ in spite of not being one of Liszt’s pupils.”

Our ears are by now accustomed to a classic approach (as opposed to Dionysian, for pianists of the latter belief are long gone) yet Friedheim’s classicism has the same sense of struggle marking new music which seeks to astound with its innovation. This is an archaic classicism, one that has vanished as the Apollonian, aided by dry musicology and dull but correct playing editions, has become a decadent and ignorant closure.

As indispensible as his recordings, Friedheim was a profundly gifted writer whose unpublished manuscripts were edited into Life and Liszt , an essential document which conveys his now-historic existence and the philosophical stance with which he confronted the world. He was also a man of great humor and wit: Friedheim’s closest friend was Moriz Rosenthal. Both pianists would flex their university-days Latin and Greek by conversing in these archaic tongues. Friedheim’s son Eric told this writer that his father devoured two branches of literature: Philosophy, as distilled by Schopenhauer, and Intrigue, for the young Eric’s duty was to obtain Detective Story Magazine for his father as soon as the latest issue reached the newsstands.

Friedheim had studied with Anton Rubinstein before heading to Weimar. He brought Liszt his own piano concerto, which Liszt accompanied at the second piano. Juggling concerts with composition, Friedheim worked on an opera, The Last Days of Pompeii . He composed throughout his life and tragically, many manuscripts were destroyed in a fire and from the chaos of the Second World War. As a teacher he highly influenced his pupils: Rildia Bee Cliburn trained her son Van Cliburn in Friedheim’s way. Colin McPhee, who studied with Friedheim in Toronto, went on to become a great writer and innovator who brought Balinese and Javanese gamelan music to the West. Friedheim wrote of him:

“I have received from far-off Java a letter from. . . Colin McPhee, perhaps the most gifted pupil I ever had. I felt a personal sense of loss when, after I left Canada, he gave up the piano altogether and applied himself entirely to composition. Now he is in Java and other distant lands, seeking new inspiration in the relatively unfamiliar native music. Yet I must not criticise him because he has neglected my favorite instrument. Did I not do the same thing when I was his age?”

Friedheim recounts his meetings with Emile Zola, Turgeniev, Liszt, Bulow, Bruckner, Brahms and the deep friendship with Saint-Saens which fell apart when Friedheim and Rosenthal pressured their colleague to speak out for Dreyfuss.

Friedheim’s too-few recordings and lucid perceptive writing conveys with striking modernity the essence of how a progressive mind and devoted artist interacted with the central cultural figure of his age and the after-effects of this experience translated into sound and words.

© Allan Evans, 1996