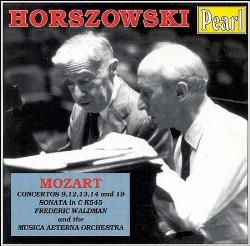

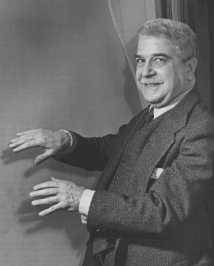

After his death months before his 101st birthday in 1993, Bice Horszowski Costa and I looked through the library of her late husband, the pianist Mieczyslaw Horszowski. Before his frontal vision vanished through macular degeneration at the age of eighty-nine, he was very welcoming, especially backstage after his Mozart concerti at the Metropolitan Museum. When I attempted to thank him for playing the lesser known opuses, he brushed off all compliments to exult in Mozart: “Not one note can be added or changed to make it better!” Each year after his ninetieth birthday found him miraculously returning to perform a new program prepared with his wife who assisted the memory of what his eyes no longer deciphered. The conductor Frederic Waldman, with whom he gave two cycles, met the pianist soon after his eyesight worsened, hearing him bemoan the worst: that it prevented him from learning new works.

As a teacher, Horszowski rarely commented, preferring to communicate in sound. His rare remarks hit their targets: to a student struggling over Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, he was advised to work on it during a vacation. Upon returning, he listened and after a pregnant pause, offered “It’s VORSE!” Another student imposed overbearing force onto Schubert to be informed that “zere are NO TIGERS in ze VIENNA VOODS!”

In his 97th year, he received me at his Philadelphia home for an interview. I was preparing a CD set with a performance of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations played when he turned ninety. It would have been absurd, with Horszowski still alive, active, and alert, to dump more ready-made information into the ubiquitous ongoing pageant of names and dates surrounding the music history forced down one’s gullet. These formidable variations were a premonition of Twentieth Century music, virtually bypassing the Nineteenth Century.

Well, how did did he learn them? Slightly arching an eyebrow, he turned aside, commanding his wife to bring several hefty volumes in from his library. All books in position, he began:

“You see, I had an urtext to start with and then found a first edition. I was able to gain access to the autograph. Do you know von Bülow’s edition? [Horszowski held it up to a page that had extensive footnotes, a familiar sense of where to turn as he no longer could see a page’s contents.]

“It is very inaccurate but if you have the unedited music you can see what he has changed. But his commentary is very important.” Horszowski then produced Artur Schnabel’s edition:

“It is a forgotten work, never reprinted, and with important comments. I also heard him play the Diabelli four times in one season. I began to study them in 1949 [when he was 57 years old]. I also played for Toscanini and Casals and they made comments. I read Tovey on Beethoven. It’s important to know as many works by a composer as possible”

Horszowski paused to lean back on his chair, inhaling:”Then I meditated on it all.”

Decades of searching the globe for Horszowski’s recorded concerts led to Chopin performances that I’ll finally restore and soon publish. While he played in major American and European cities, Horszowski, a former Milanese resident, delighted on his Italian tours down south in Bari, Pistoia, Perugia, especially drawn to the Tuscan mountain town of Castagno d’Andrea which aroused his passion as an Alpinist who scaled the Matterhorn three times.

Their local priest offered the town’s church for his recitals and recorded them all. Another trip to Gorizia by the border with Slovenia had him playing Chopin’s Andante Spianato and Grand Polonaise, the only occasion in his last three or so decades, captured by an enraptured listener. The art of rubato heard here edges close to descriptions of the composer’s playing. A 1980 evening in Pistoia channeled Chopin moreso than any other yet to surface.

My own contact with his Chopin developed during his last sixteen years of activity and by listening to his few recordings. Each encounter with his art was one musically and spiritually enlightening, and with it came a gripping intensity of hearing him play like a God, then exiting off the stage to leave in his wake a comet’s tail of gratitude tinged with sorrow that it would, at any moment, be over.

Watching his diminutive body change its language with each composer, he slightly bent forward in Bach, abstaining from pedal. With Chopin his arms had a specific choreography as each composer was to be physically evoked in their unique sound worlds. His Bach arrived as a series of unfolding, overlapping waves, each laid bare for observation while intimating alternative possibilities, piling up into a labyrinth of potential perceptions hovering above their earthbound reality. Behind and within each space and sound came an infinity that arose and vanished inside time’s momentum.

Horszowski’s moderate tone expanded in Chopin to fill an entire space, saturating each cubic centimeter even during soft or chiaroscuro passages. His pedal floated the sound as a force to completely envelop you, flowing from the aether into him and translating itself into the air, guided by his fingers tracing their motions.

With Horszowski’s passing, the unknown steps behind his exploration of Chopin seeming irretrievable, and as he hermetically put a lid on his ideas and thoughts, we were at a loss to decipher the way he came to unlock Chopin’s enigmas. Horszowski’s mother, his first teacher, had studied with Chopin’s assistant Mikuli and there were other pupils at large, such as Moriz Rosenthal and Raoul “von” Koczalski, whose recordings varied from illumination (Rosenthal) to a dim bulb (Koczalski).

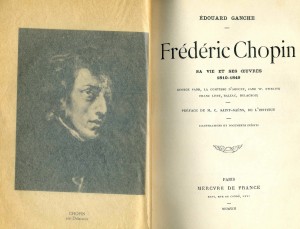

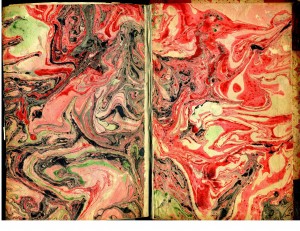

While taking time off from performing to attend philosophy lectures by Bergson at the Sorbonne around 1914 and immerse himself in reading, Horszowski obtained a new biography of Chopin by Edouard Ganche. Its binding and paper immediately aroused interest:

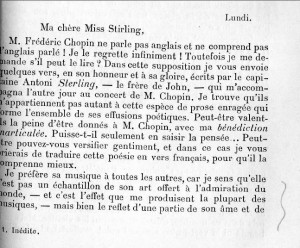

A book that never left him, it was his companion from Paris to Milano, during an escape from war torn Europe to Sao Paolo, then New York, and to his long and final residence in Philadelphia. Horszowski began corresponding with the author a decade after the book entered his life. Inside his copy were faint tracings alongside chosen passages. His pencilled clues created a subpath by isolating comments, excerpts from Chopin’s letters, all meekly indicated in the thinnest line of hardly visible pencil.

By doing so, Horszowski became a tacit presence that actively indicated every line that snared him: Chopin’s completion of a work yet to find its name (the Polonaise-Fantasie), a return trip from a hellish holiday in Majorca with George Sand amidst the stench and constant squealing cargo of one hundred swine whose din didn’t abate during Chopin’s strenuous breathing and his coughing up of tubercular blood.

Chopin’s friendship with the artist Delacroix attests to more than a portrait with Sand:

Went with Chopin for his drive at about half-past three. I was glad to be of service to him although I was feeling tired. The Champs-Élysées, l’Arc de l’Étoile, the bottle of quinquina [bitters aperitif], being stopped at the city gate, etc.We talked of music and it seemed to cheer him. I asked him to explain what it is that gives the impression of logic in music. He made me understand the meaning of harmony and counterpoint, how in music, the fugue corresponds to pure logic, and that to be well versed in the fugue is to understand the elements of all reason and development in music. I thought how happy I should have been to study these things, the despair of commonplace musicians. It gave me some idea of the pleasure which true philosophers find in science. The fact of the matter is, that true science is not what we usually mean by that word – not, that is to say, a part of knowledge quite separate from art. No, science, as regarded and demonstrated by a man like Chopin, is art itself, but on the other hand, art is not what the vulgar believe it to be, a vague inspiration coming from nowhere, moving at random and portraying merely the picturesque, external side of things. It is pure reason, embellished by genius, but following a set course and bound by higher laws. And here I come back to the difference between Mozart and Beethoven. As Chopin said to me, ‘Where Beethoven is obscure and appears to be lacking in unity, it is not, as people allege, from a rather wild originality – the quality which they admire in him – it is because he turns his back on eternal principles.’ Mozart never does this. Each part has its own movement which, although it harmonizes with the rest, makes its own song and follows it perfectly. This is what is meant by counterpoint, punto contrapunto. He added that it was usual to learn harmony before counterpoint, that is to say to learn the succession of notes that leads to the harmonies. In Berlioz’s music, the harmonies are set down and he fills in the intervals as best he can. Those men, who are taken up with style that they put in before everything else, prefer to be stupid rather than not to appear serious. Apply this to Ingres and his school.–Eugene Delacroix. Journal entry of 7 April 1849

One of Horszowski’s students kept a trusty device hidden from prying authorities and thus saved a great many concerts. Neglected by the record industry until a late effort arose after his 94th year, such action rescued a great legacy before it vanished. One such moment comes from the final season in his ninety-ninth year: an encore of Chopin’s Valse in C sharp minor comes to life in a 19th century style amidst audience noises that carry you from a state of joy to a sorrowful premonition of impending loss; the Valse was played at what became his penultimate concert.

We continue searching and publishing in gratitude for what Horszowski offered us.

Allan Evans ©2013

Arbiter will soon publish a 2 CD set of Chopin played by Horszowski, containing English translations of all the passages the pianist traced into the margins of Ganche’s biography of Chopin.