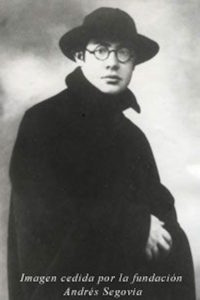

A pioneer who took the guitar away from flamenco and into global concert life, Andres Segovia was an innovator who luckily commissioned composers for what seemed to be a new instrument as many could not imagine it apart from café settings. I managed to hear three recitals of his when he was past eighty: twice at Lincoln Center, which had such wretched acoustics that if you wiggled in your seat he would be drowned out and the 92nd St. Y where his music was finally audible.

Segovia’s earliest recordings project a romantic who occasionally sentimentalizes with slides that slither into being overly expressive. A Bach example from c. 1927 shows his novelty in transposing keyboard and violin music, something Bach did all the time in each and every direction as the integrity of his notes could succeed with any format.

Prelude, Allemande, & Fugue:

One piece new to the non-guitar world was Francesco Tarrega’s tremolo study, written right before Segovia’s birth but not well known beyond a few musical circles.

This piece and othesr from his nation are among the best facets of his art as he thrived in their origins and how they fired composers like Albeniz to take them into his Modernism:

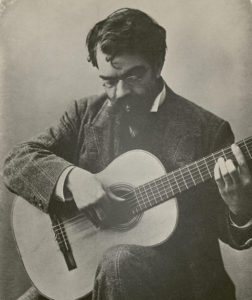

Slightly younger than Segovia was Diego del Gastor who went quite far with Flamenco and merits as much attention as Segovia (thanks to Anna Wayland for bringing him to everyone’s attention!)

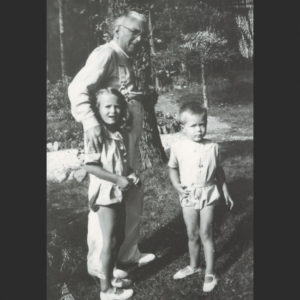

Hitting the concert circuit, Segovia and others had the Madrid impresario Quesada arranging tours throughout South America. One time he collided with Spain-loving Artur Rubinstein and Ignaz Friedman. The pianist’s granddaughter Nina Walder (seen with grandpa Ignaz and her brother Paul)

managed to have an informal talk (in French) with him and one excerpt is translated in my Friedman biography:

In Argentina, Friedman toured with Andres Segovia, who was eleven years younger: the two were fast friends. Segovia recalled:

“ [Friedman’s itinerary] was fuller than mine because it encompassed Brazil and Chile and I was simply engaged for Buenos Aires, other large towns and in Uruguay only Montevideo. So he went twice to Chile, twice to Brazil. I had to go to Mendoza and knew that Friedman was going to play there, not a public concert, but a private one in the most exclusive casino in Mendoza. I attended his concert at this special aristocratic club. Naturally the public gathered there was not musical, an audience of rich people who had nothing to do with music and I remember something very funny. During the concert he noticed immediately that they were not musical. At the end of a variation on a theme of Paganini [La Campanella] he fell asleep during the trill to attract the attention of the audience. There was a colonel wearing many decorations which were later abandoned as they hadn’t had any wars in Argentina and this colonel slapped Friedman’s shoulder and said ‘What did you play- is it Mozart or yours?’ Can you imagine! Friedman answered ‘LISZT’: the colonel said ‘Ah!’ and disappeared.

“The next day we took the train to Buenos Aires and we passed through a desert which created a dust, such a fine dust that entered through the window’s cracks and one had to ask always for a damp towel from the conductor to line the windows. When we arrived I saw placards for [Artur] Rubinstein’s concert. So I tell Friedman ‘We are going tonight.’ Friedman refused but then accepted. The impresario Quesada reserved a loge that faced Rubinstein. He started with a Chopin Nocturne. Then, as Friedman was preparing himself to suffer the Chopin, Rubinstein suddenly saw Friedman and completely lost his nerves and played in a very nervous way. Ignaz took my arm, saying ‘this is not right, this is not so!’ and I said ‘It’s not me who’s playing.’ Then came works of Albeniz. Albeniz wrote his music in a terribly difficult way. Sometimes [Rubinstein] simplified or played it wrong and it was I then who took Friedman’s arm saying ‘It is not so!’ Afterwards we went to see him and Friedman said ‘Artur, good, very good, especially Albeniz.’ Then when I came, ‘Artur, good, very good, especially Chopin.’”

[photo: Rubinstein’ Polish count-diplonat; Friedman. mid 1920s]

Sit back and brush up on your French as Walder and Segovia let their conversation go wherever it cares to:

part one:

part two:

Nina Walder, Lydia Friedman Walder. (Friedman’s Blüthner piano, living room in Villa Friedman, Siusi, Bolzano, summer 1982)

Rubinstein and Friedman knew of each other since 1910 if not earlier. According to Rubinstein, they shared an evening in Lemberg (L’vív). Rubinstein sat backstage as Friedman played the first half, then the joined forces for a Chopin’s Two-Piano Rondo.

The younger Artur described how his crowd was impatient to hear him and out he went to dazzle in the second part of their show and that Friedman took being bested in a gentlemanly way!

Ella Brailowsky (wife of the pianist Alexander) once described Rubinstein’s Memoirs as fiction. My favorite part are any and all sitings of Kapnik, a shnorrer (moocher) who always seemed to empty Artur’s pocket, as if he had some blackmail and had to be paid off: Kapnik always impressed as being a fictitious realization of Rubinstein’s alter-ego who was compensated as a way of keeping a disliked part of himself at a distance.

Now, now, now! Rubinstein is an adored cultural figure and his admirers fiercely defend his memory and legacy but if we imagine that he “bested” Friedman back in 1910, why don’t we hear Rubinstein’s very first recordings, made for the Favorit label in that year? For some reason they have always been excluded from any “complete” edition.

First the Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody no.12 (abridged due to the 4 minute playing time of a shellac):

Then a Strauss-not-sure-whose-arrangement-this-is of the Blue Danube Waltz.

Friedman’s earliest recordings came a little over a decade later and here are two examples of his Chopin: the Prelude no. 19 and Etude in G-sharp minor Op. 25, no.6 (one take for both:)

(photo: Ignaz Friedman, his only known color photo, location/date unknown)

It was a joy to discover Friedman’s playing when I was sixteen and hearing him after being introduced to Rubinstein’s Chopin one month earlier came as a revelation that compelled a 27 year of hunt to get his biography in print. An LP set for Danacord in 1985 came about when visiting the legendary Jesper Buhl in Copenhagen and his enthusiastic consent to restore and release all of Friedman’s known recordings.

Celebrating the Danacord release in Geneva, 1985 with Lydia and Nina Walder

They were later poorly and inaccurately released by others on CD format but one example of his art is on Masters of Chopin (Arbiter 158) and for those eager to pair off Friedman and Rubinstein at their height, have a listen to Friedman playing the Chopin Second Sonata’s Funeral March and Presto and then place it against anyone else’s!

Allan Evans ©2016

Thank you for this interesting post. I had never come across audio for Rubinstein’s 1910 sides for Favorit until they appeared on YouTube a week ago. I can now see that you had put them up here in 2016. I would be interested to know the provenance of these long unavailable recordings. Do you have a picture of the shellac? I ask out of interest in seeing such a historic record not because I doubt that the recordings you have posted are genuine. I have heard Friedman”s recording of Op. 55, no. 2. I shall seek out more of his recordings and your biography of him.

James Methuen-Campbell received a dub of the disc from the Towarzystwo im. Fryderyka Chopina’s (Chopin Foundation of Warsaw) archive and shared it. So amusing to read AR describe how Friedman took it in stride when he allegedly bested him, thanks to a claque that only appeared when it was Artur’s’ turn, at a shared program in 1910. Leschetizky was still alive and Friedman often dropped in on him. He had attended Busoni’s masterclasses a year earlier so I tend to sense jealousy in Rubinstein who needed to belittle a deceased competitor in his autobiography. That same year, Rubinstein lost to Alfred Hoehn in the Anton Rubinstein Competition so perhaps the Russo-Polish Favorit label recorded this disc to help boost his career. Koussevitsky was so outraged over Rubinstein’s loss that he generously funded him afterwards.

It is very kind of you to take the trouble to reply and so quickly. This is vey interesting. The 1910 Favorit recording does not seem to have come to general attention until now. I am a devotee of Rubinstein’s playing. I wonder if you have heard his recital at Nijmegen in 1963. I will definitely listen to more of Friedman’s recordings and hope to get hold of a copy of your biography of him.

Rubinstein does say when describing the shared programme in Lwow in 1910 that the public had behaved unpardonably towards Friedman in not filling the house for his part of the recital. He also says that he believes that the reason he had a full house was that Friedman was a frequent visitor to Lwow whereas Rubinstein was the newcomer and that he also benefitted from publicity arising fro his having been introduced to the local nobility. He also mentions hearing great applause for Friedman’s part of the programme.

It seems that Artur did not listen to Friedman’s solo portion and only based his opinion on the audience’s reaction.

Just compare his 1910 Favorit performances to Friedman’s 1924 discs (Etude in Thirds) to observe a substantial difference in artistry.

I do not read Rubinstein’s account as one of “besting” Friedman. He just explains the change of crowd and why he thinks that was. He does not suggest that he played better than Friedman. Rubinstein did not like the recordings he had made in 1910. As you will know he did not resume recording until 1928 and he went on making records for another fifty years. I will listen to Friedman’s recordings from 1924, but assuming that comparison is worthwhile exercise there are countless better examples of Rubinstein’s artistry, although I do understand that the point here is that the Favorit recordings give some representation of Rubinstein’s playing in 1910.

As you say, Rubinstein is an adored cultural figure and his admirers fiercely defend his memory and legacy . Friedman was obviously a great artist and on my reading of Rubinstein’s autobiography, Rubinstein acknowledges that.