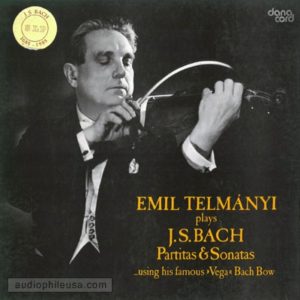

(photo: Carl Nielsen, Emil Telmanyi (1892-1988), Frida Møller and Hans Børge Nielsen depart for Frankfurt in 1927)

You find a classical musician from long ago whose sounds are more convincing than anyone around. What do you do when you stumble onto a lost culture? Were there more like him and why was it inaccessible? Take some suppression and obtusity, add a dash of mayo, and you have the recipe for an undernourished music scene with inadequate nutrition in which all sounded prefabricated. I had to hunt for Ignaz Friedman but found no resources available.

One highly-touted professor of bibliography was running a coolie-labor sweatshop by having grad students input data into something known as RILM. Lured by requirements or the need to know how knowledge is labelled and sorted, it held out hopes that anything relevant to classical music resources would be codified. Instead it proved to be SLIM and is still useless as it lacked anything relevant to Friedman. “How did you not take Barry’s class?” his book-editor widow inquired when I presented her a proposal. “I knew better!” was my tacit reply as she turned down the manuscript on unpublished writings of a Liszt-Brahms pupil.

The only road is the lone road, of empirical serendipity, desultorily leading to what the trail of musicological writings cannot access as the vivid sources are alive or preserved in sound. Having been taken in as family by Rev. Gary Davis and his wife Annie,

I entered their private world and was exposed to what lay behind a master musician’s art. A month after Davis’s death I first heard the long gone Friedman on a recording, who had the same energy as Davis, proving that a higher echelon spanned all genres of music. As Friedman had performed throughout the world, it seemed likely that anyone of a certain age could have heard him or even known him and so began a journey to over thirty countries over two decades. A methodology arose of entering a new city, getting maps, finding libraries and archives, contacting any older musician and something or someone always turned up, from Iceland to South Africa and Singapore.

Friedman had a rocky marriage and left his wife and daughter behind in Berlin to ride out what turned into World War I in the safety of Copenhagen. His career was enlivened by contact with members of cultured societies and diplomats who allowed him to have supplies sent back to deprived war-torn Berlin through their diplomatic pouches. Many interviews turned up in Danish archives and one day in the August of 1983 an intriguing lead appeared. Danacord, a record label based there had just released recordings of a Hungarian violinist who had premiered the Carl Nielsen violin concerto. Its liner notes mentioned how Emil Telmanyi was brought to Denmark by Friedman in 1910 where he soon married Nielsen’s daughter and became their foremost violinist. He experimented with a bow-maker to create a curved device able to play Bach’s Chaconne with unbroken chords and recorded all the unaccompanied works.

Albert Schweitzer showed interest and is mentioned in Telmanyi’s autobiography.

i called the label at once to learn from by Jesper Buhl, their guiding light, that Telmanyi was not only alive but actively conducting a local orchestra and lived nearby. I soon caught a commuter rail up to their northern town of Holte, chugging past Norreport’s bricks and breweries, heading into greener countryside. Not too far away, a soothing walk along woody curving streets led to the Telmanyi house. His wife Annette and daughter Ilona provided a warm welcome. Annette and Emil married after marriage with Nielsen’s flapper daughter flopped. Annette was a pianist and string player and their three daughters formed a family chamber ensemble. Telmanyi was in his ninety-first year and was curious about why I was looking into Friedman. It seemed no one had asked much about his earlier life and he encouraged me: “What you’re doing is important!”

He brought over scrapbooks of chronologically organized program books, knowingly flipping through some 1909 recitals. one had a Frigyes Reiner as his accompanist, later known as Fritz, a formidable tyrant of the Chicago Symphony. He related his meeting Friedman in Berlin when he gave the continental premiere of Elgar’s Violin Concerto in 1909 and Friedman caught him backstage.

Telmanyi’s hands were arthritic, his eyesight failing, but he lovingly caressed his violin: an Amati. “Imagine, this instrument was already an antique in Mozart’s time!” His music study had an overheard projector to enlarge music scores so that he could see enormously magnified lines to learn new works for each season. He was engaged in absorbing Mozart’s First Symphony, going through it part by part.

We sat down and Telmanyi began answering. One aims to dive deep into a subject but the ground his talk broke opened an entire musical universe lived in by a still active protagonist whose fresh mind and sharp memory vividly brought to life events from the 1890s and on. Luckily he left an autobiography, written in Danish. Our first encounter was recorded and includes surprises about Friedman, Busoni, Bartók, conveyed with an infectiously sympathetic spirit.

The cassette recorder’s battery died and left a mouse-like chatter rising into subsonic frequencies before it bit the dust but only now could most of it be saved through software. It breaks off in the sound track when Telmanyi went full steam into musical examples.

A month after meeting Telmanyi I was introduced to the Budapest-based harpsichordist János Sebestyén, a living historical treasury who opened doors to Antal Molnar, then two years older than Telmanyi (and would be gone within months after he received me), who was not only the violist in the Waldbauer-Kerpely string quartet that took part in Debussy’s appearance as a pianist on his 1910 Budapest visit. Molnar reached high up, aided by a stool to pull down a hefty book, one among many red identical volumes on crowded shelves and sang a melody that he had found and transcribed when accompanying Bartók and Kodaly into the field before World War I, delighting in a work that still overwhelmed him after having gone as a Third Man to capture folk songs. János’s weekly radio program were themed to review what had happened in Budapest decades ago on varying anniversary dates of his show, allowing pre-totalitarian life to return in full under the guise of nostalgia. One who offered advice to archivists who began restoring x-ray plates containing radio broadcasts of Bartók at the piano, he managed to get a copy of Telmanyi with the composer Erno Dohnanyi playing Schumann’s D minor violin sonata, broadcasted in Budapest c. 1939-1940.

The Soviet-controlled regime has fizzled out and János is no more, but a website conveys his style and society. It’s time to share the performance, warts and all (notes were lost whenever a new disc was set up on the recording turntable). The duo had given numerous sonata recitals over two decades and we are fortunate to hear them in the act, as Dohnanyi soon declined, in part from his loathing to practice and both came more to life in concerts than within the pressures and limits of a recording studio.

Although I approached Telmanyi with one question, I ended up leaving with more open doors than I can ever count. We had two more meetings over the years. He passed away in 1988 in his ninety-sixth year. At our last get-together, the image still remains as he and Annette held hands, seated on their couch as we were taking leave, both breaking in to advise Beatrice Muzi and me (whom I would soon marry) to see how their happy marriage came from getting each other to laugh and, eyeing one another, an erotic attraction.

–Allan Evans ©2016

wow!!!! thank you allen

Great, Allan, hope it will be a chapter from a new book !

It should be but a page cannot capture Telmanyi’s laughter.