Disc 1

Carl Friedberg, piano: tracks 1, 2, 4-9, 13, 17 (rec. 1948-51) Johannes Brahms, piano: track 3 (rec. 2 Dec. 1889) Trio of New York: Carl Friedberg, piano; Danil Karpilovsky, violin; Felix Salmond, cello: tracks 10-12, 14-16 (rec. 1939)

- Chopin: Polonaise in f#, Op. 44 9:59

- Schubert: Moment musical in f 1:39

- Brahms: Improvisation on Josef Strauss' Libellule: Polka-Mazur 0:45

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata in F, Op. 10, no.1: I. Allegro molto e con brio exc. 0:39

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata in F, Op. 10, no.1: II: Adagio molto 7:13

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata in F, Op. 10, no.1: III: Prestissimo 3:02

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata in e, Op. 90: I: Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus 5:11

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata in e, Op. 90: II: Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorgetragen 7:06

- Beethoven: Rondo a capriccio, Op. 129 5:48

- Brahms: PIano Trio in B, Op. 8: I. Allegro con brio (ends at double bar) 3:50

- Brahms: PIano Trio in B, Op. 8: III. Adagio non troppo (starts at m.27) 6:09

- Brahms: PIano Trio in B, Op. 8: IV. Finale. Allegro molto agitato 5:55

- Brahms: Rhapsody in b, Op.79/1 (incomplete) 2:49

- Brahms: Piano Trio in c, Op. 101: I. Allegro energico 7:06

- Brahms: Piano Trio in c, Op. 101: II. Presto non assai 3:29

- Brahms: Piano Trio in c, Op. 101: III. Andante grazioso & IV. ms. 1-14 4:28

- Brahms: Ballade in g, Op. 118, no.3 3:29

Disc 2

Edith Heymann, piano and speaker; tracks 1-16 (rec. 1949) Carl Friedberg, piano; tracks 17-20, 22, 37 (rec. c. 1951) Marie Baumayer, piano; track 21 (rec. 1910) Ilona Eibenschutz, piano; tracks 23-24 (rec. 1950s, 1903) Etelka Freund, piano; tracks 25-36 (rec. 1959, 1951)

- Talk on Clara Schumann I 4:50

- Schumann: Fantasiestücke, Op.12: Des Abends exc. 1:13

- Clara Schumann on tempo 0:39

- Schumann: Fantasiestücke, Op.12: Grillen exc. 0:47

- Comments on Clara Schumann 0:35

- On Schumann's Kinderszenen, Op. 15 0:15

- Schumann: Kinderszenen: Hasche–Mann exc. 0:36

- On Clara Schumann 0:19

- Schumann: Faschingschwank aus Wien, Op.26: Intermezzo exc. 1:01

- Clara Schumann as teacher 2:26

- Beethoven: Sonata Op. 31, no.2 in d: III exc. 0:23

- Clara Schumann as Bach interpreter 0:45

- Bach: Well Tempered Clavier Bk.I: Fugue no.2 in c minor exc. 0:29

- Clara Schumann on Bach 0:38

- Bach: English Suite no. 3 in g: Gavotte 1:42

- Heymann’s closing remarks 0:26

- Friedberg recalls meeting Brahms 2:59

- Brahms: Rhapsody Op. 79, no.2 in g exc. 1:40

- Friedberg discusses Brahms 3:10

- Beethoven: Sonata Op. 111: II exc. from lesson 1:23

- Schumann: Pedal Etude in A flat, Op. 56, no.4 3:58

- Schumann: Arabeske, Op. 18 (extracts) 1:45

- Schumann: Kreisleriana: IV sehr langsam 2:00

- Brahms: Ballade in g, Op. 118, no.3 2:37

- Brahms: Variations on a theme by Schumann, Op. 9. 15:21

- Brahms: Rhapsody Op. 119/4 repeated with the Intermezzo Op. 76/3 in A-flat 8:13

- Bartók: Elegy, Op. 8b/2 molto adagio 6:22

- Bartók: For Children: XXVI. Go round,sweetheart, go round 1:03

- Bartók: For Children: XXXVII. When I go up Buda’s big mountain 0:22

- Bartók: For Children: XXXVIII. Ten liters are inside me 0:42

- Bartók: For Children: XXXIII. Stars, stars, brightly shine 1:08

- Bartók: For Children: XXXIV. White lady’s eardrop 0:56

- Bartók: For Children: XIII. A lad was killed 0:59

- Bartók: For Children: XL. May the Lord give 0:51

- Bartók: For Children: XVII. My little graceful girl 0:56

- Bartók: For Children: XXXXII. Swineherd Dance 1:27

- Brahms: Piano Concerto no. 2, Op.83: lesson advice 0:41

Carl Friedberg plays the introduction to Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in d :

Max Fiedler conducts the introduction to Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in d [Arbiter CD 160]:

If there is someone whom I have failed to offend, then I sincerely apologize! –Johannes Brahms

Today Brahms is played everywhere and listeners expect his music to be shaped into a well-defined, inflexible entity. However, our newly discovered recordings overturn this accepted view of his art. In these performances we are exposed to a language that gradually disappeared soon after the composer’s death in 1897. All of the performances on this compilation were given by pianists who heard and knew Brahms, and who received his musical blessings. They all understood that Brahms composed new music, flirted with improvisation, and was influenced by ethnic rhythms and idioms. Their perception of the great composer is so vastly unlike that of musicians and audiences today that the difference cannot be overstated.

With Brahms’s pupil Carl Friedberg, the Chopin Polonaise in f-sharp minor from a New York recital reveals a musical mind able to seize on and deploy its anguished narrative. One striking example is when Friedberg conveys the terror residing in a transition that Chopin set up as a galop that evolves into a prominent mazurka. Brahms had a marked affinity for Chopin’s music and Friedberg’s interpretation captures a lost 19th century approach. An insistent rhythmic drive in Schubert’s Moment musical No. 3, played at a Kansas City recital pulsates like the motoric drive of a neglected improvisation recorded by Brahms on a cylinder in 1889. [CD I: track 3]

My first impression of Brahms came many years ago with the opening of his Second Piano Concerto’s second movement. The music was gripping and enticing, but alas, subsequent encounters with the piece seemed to lack an essential primal quality. Instead of admiration for a compelling master, I developed a strong aversion to Brahms’s music. Later I blamed myself for initially misjudging his merit due to the dull and unimaginative interpretations I’d heard. I had come to revile Brahms’s music at the hands of indifferent performers who ignored the composer’s rhythm and spirit. Whatever texture or tempo was requested, all muddled into a uniformly plodding sonic muck. Brahms presented as an austere cultural institution reigns as a norm in our music world.

Yet, along with this loathing a gut feeling told me there must be a truer representation of this undeniably great composer’s art, and in order to find it one had to elude a mummified Brahms. Pervasive sterility occupied and controlled how his music was reflected on, presented in the media, on stage, in published reviews, in the din of home-made opinions. Tumescent scholarship further obscured Brahms’s traces through bloated verbiage and analyses that failed to examine relevant sound recordings.

So, where and how does one even begin to find the genuine Brahms? A clue appeared in 1977 when, alone and determined, I took a Brooklyn-bound D-train to the Foster Avenue stop. Phil Stern’s apartment overflowed with shellac and vinyl. His invite was a consequence of having visited Manny’s Books and Records where I was presented to Stern by the store’s proprietor. His dusty cramped shop attracted discophiles who congregated to challenge one another’s taste, boast over their catches that dissipated into a laundry list of character-assassinations. When Stern assayed my musical preferences he realized that not only would I, a curious nineteen year old neophyte, benefit from his mentoring, but would gain a younger ally who, through exposure to his aesthetic guidance, would buttress his views. Although he lacked musical training, Stern possessed a sophisticated ear that was confounded by his being overly opinionated.

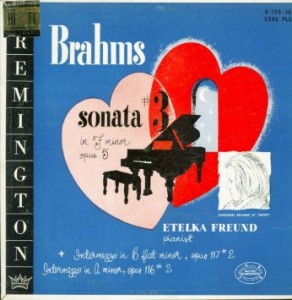

When avowing my antipathy to Brahms’s music he wagered that I hadn’t ever heard Etelka Freund, a name absent in music reference books. Stern loaded her one and only Remington vinyl LP of Brahms onto a gadget-ridden British-made turntable favored by collectors and piloted a lever that brought its tone-arm down into the opening groove.

Out came a sensuality enlivened by deft accents, projecting a melodic rainbow, while her rhythms evoked those of later syncopators. Deep metallically vital hues came to the fore to serve as guide to the works’ destinies. I understood at once that she had been a musician of crucial significance who demanded investigation. Some years earlier my first epiphany struck when Ignaz Friedman, another lost past-master, was aired on the radio after a thrift- shop find of a 78rpm shellac of his playing Chopin. Like Freund’s disc, the recording remained unavailable outside of private collections. Manfred Clynes,

an Australian scientist and Friedman pupil, weighed his teacher’s Chopin B minor Sonata with Artur Rubinstein’s: “Rubinstein played it very well but it’s like night and day in terms of the subtlety and the emotional impact. [Friedman’s] moved you to tears whereas Rubinstein moved you, yes, but not in that . . . [Clynes laughed] it’s like moving from Pomona [a suburb near Manhattan] to New York City, and moving from Pomona into a different world altogether. Friedman could do it.” My search for Friedman led me to adopt a methodology that relied heavily on ethnography (a methodology that might well serve other musicians.) With the appearance of what sounded like a genuine discovery it was the time to proceed on my search for a revivified Brahms, but where was Freund?

Unflagging obsessive interest in Friedman led me to pursue a Manhattan memorabilia expert, one who had no idea that my taste clicked with that of Stern, a rival whom he loathed. Bitter differences festered in a sub-cultural tension that divided collectors into factions that viciously despised one another in their goals of seeking domination and control of important historical recordings and their publication. A series of his last minute cancellations abated and I was served up over two hours of exhibitionistic soliloquy laced with gossip. When I mentioned Freund, he described a recent futile attempt to lure materials away from her son: “He’s difficult and won’t let anything out.” He provided a phone number, warning that it would be a waste of time as her son was obstinate and uncooperative.

Advice is often best when ignored so I phoned Nicholas Milroy

and days later arrived in West New York, New Jersey where several towers above the Hudson River faced onto the Manhattan skyline. On the twenty-third floor, a tall, trim, goateed man approaching seventy with sharp sparkling eyes and Cheshire cat grin intercepted me by the elevator. That 1979 meeting led to a decade of enthusiastic, collegial research that was enlivened by enticing aromas emanating from the kitchen. Above a cabinet flanking his crowded pipe rack rested three segments of a ceramic sea serpent, lolling idly as its bulges transformed the flat surface into an ocean masking a good part of their sea-monster curves – quite the metaphor as I later learned of the ingenuous ruses my new host employed while serving as an intelligence officer with the U.S. Army during World War II. In a deep, sonorous voice redolent of his Hungarian roots, Milroy confirmed that Etelka Freund, his mother, had passed away two years earlier at age ninety-eight (1879-1977).

Milroy opened folders bulging with letters and manuscripts pertaining to his mother and documents concerning Robert Freund (1852-1936),

Etelka’s step-brother, who had vanished into an even greater obscurity than his sister. Uncle Robert had merely studied with Carl Tausig, Beethoven’s friend Ignaz Moscheles and later became a private pupil of Liszt’s and befriended Brahms.

We met monthly to translate and annotate Robert Freund’s memoir manuscript and correspondence with Busoni, Bartók and others, a project spanning several years, with a pause at noon when Milroy’s wife Clarice served her exquisite Hungarian dishes. Milroy remarked that the young Ilona Eibenschutz was appreciated by Brahms not only for her talent and beauty but the renowned Hungarian cuisine prepared for him by Ilona’s mother who has reputed to have been one of the finest cooks in Budapest.

As we uncovered Robert’s memoirs and correspondence, fleshing out names and details, Milroy cited collective family memories that he had grown up with and those experienced first-hand. Brahms’s role in the Freunds’ lives was crucial, a legacy that had been left entirely unexamined since the composer’s death. Brahms’s sixtieth birthday trip to Italy in 1893 was planned by Uncle Robert and other close friends. Milroy confirmed that Etelka was given private piano lessons from Brahms after their weekly lunches at the composer’s apartment during the half year she spent in Vienna in 1894. Later in Budapest she befriended a younger pianist and budding composer: Béla Bartók.

At Robert’s request she proceeded to Weimar where she became a favored pupil of his friend Busoni, who presented her to Sibelius. Following the Freunds’ advice, Bartók approached Busoni in 1908: their encounter led Busoni to have Bartók conduct a work of his in Berlin, an event that introduced him as a new musical force. In a letter to Etelka, he quoted Busoni’s commenting on his Fourteen Bagatelles: “At last, something truly new! I hold these pieces to be among the most interesting and original of our times; what the composer has to say is out of the ordinary and entirely individual.”

As Etelka Freund’s life lasted nearly a century, I asked Milroy if any journalist or musicologist had ever interviewed her. “No.” He noted that his mother remained in top pianistic form until his father passed away when Freund was 89 years old. Years earlier, soon after Freund and her husband settled in New York in 1946 after having survived the Nazi and Russian occupation of Budapest, Milroy organized a few solo concerts for his mother. An orchestral debut in Washington garnered rave reviews, one even comparing her to the fiery Teresa Carreño. Nevertheless, music managers quashed any follow-up engagements by claiming Freund’s age (68) was a liability.

Freund sometimes appeared on a New York radio station playing live. Milroy sought to preserve what he could by recorded several off the air, programs with works by Liszt, Brahms and Bartók among others. His decision not to release Freund’s radio performances was prompted by the occasional missed note and an announcer who intruded before a piece was about to end. Milroy eventually consented to the publication of over two hours of her playing, with more coming to light here and in future Arbiter projects.

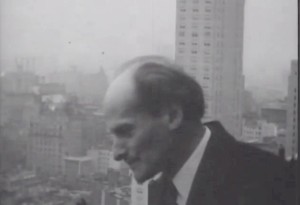

During the time Bartók spent time with the Freunds, his maturation was followed as he brought them new compositions and field recordings of folk music, once lugging cylinders and his trusty Edison machine over for playback. One supposes an ethnographer like Bartók would not have overlooked the many chances to question the Freunds about their personal contacts with Brahms, Liszt, and others. When Robert Freund died in 1936, Etelka inherited the manuscript of Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto, given to her brother after the composer’s death. Bartók volunteered to smuggle it out of Fascist Hungary: while packing for a move to the United States in 1941, Bartók removed its title page, one that identified Brahms as the author, and slipped it inside a folio of his own sketches to avoid it being seized by Gestapo border agents. Bartók died one year before Etelka Freund emigrated to New York: in her baggage was the missing title page. A concert broadcast of Béla with his wife Ditta Pasztory-Bartók playing Brahms’s Piano Quintet in the two-piano sonata version displays the way Bartók understood Brahms and how Brahms influenced his own music. Extant recordings of Bartók and Freund attest to the composer being but one step away from Brahms, a composer he missed meeting by only a few years. Perhaps unintentional, a link is audible in Freund’s playing of Brahms’s final piano work, the Rhapsody Op. 119, No. 4 at 2:53, which alludes to Bartók’s own recording of the Fifth Dance from his Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm.

Brahms’s own arrival is the subject of an 1853 article written when the twenty year-old composer was discovered. In New Paths, Schumann writes:

I thought [that] there should and must suddenly appear one called to give

voice to the highest expression of the times in an ideal way, one who would bring us mastery not in gradual developments, but rather, like Minerva, should spring fully armored from the forehead of Zeus. And he has come, a young blood, over whose cradle the graces and heroes kept watch. He is called Johannes Brahms, from Hamburg, creating there in dark tranquility, but instructed in the most difficult precepts of Art by a felicitous and enthusiastic teacher, who had been recommended to me previously by a known and venerated master. He bore, as well in his outward appearance, every sign that would announce to us: this is a chosen one. Sitting at the piano, he began to reveal wonderful regions.

In 1862 when Brahms was twenty-nine, the critic Eduard Hanslick

foreshadowed what would evolve into a lifelong struggle: the composer’s need to balance an innate gift for melody, rhythm and style with his overly analytical mind, to ensure that overly self- conscious strategies wouldn’t bog Brahms’s imagination. This struggle led Brahms to trash the major part of his attempts, only preserving a fraction of his efforts. Hanslick ponders: “Will his originality of invention and melodic richness hold pace with the ultimate development of his harmonic and contrapuntal art? Will the natural freshness and youthfulness continue to bloom untroubled in the costly vase that he has now created for them?”

Although formal schooling ceased at age fourteen, Brahms’s life-long process of self- instruction led him to amass a personal library that comprised more than two-thousand items. Early on he began to copy poems into an aesthetic breviary, and throughout his life would strip down compositions and musical treatises to analyze past practices, as well as the strategies of his contemporaries. In an astute, pathbreaking dissertation, Dr. Elaine Kelly described a creative process that refutes the commonly held notion that Brahms the musician was an inflexible conceptualist, one who shunned depictive effects: [referring to Rhetorical Devices in Johann Mattheson. Kern melodischer Wissenschaft. Hamburg 1737, a book in Brahms’s library] “Markings are important, not only giving rise to the question of what role rhetoric played in Brahms’s own compositional process, but also challenging Hanslick’s apotheosis of Brahms as the ultimate absolute composer. Hanslick’s idealisation of Brahms as the saviour of abstract music, writing compositions which were ‘purely musical in conception and structure and purely musical in effect…’ has had a hugely influential effect on subsequent Brahms literature, shaping the 20th century image of the composer. That Brahms himself, unlike Hanslick, was not totally opposed to programmatic music is evidenced in his admiration for Berlioz and Wagner, and his interest in Mattheson’s statements on the scope of descriptive music indicates that he was not adverse to the compositional possibilities offered by extra-musical influences.” [Kelly. A More Beautiful Era of Art. dissertation. 2002. p.202]

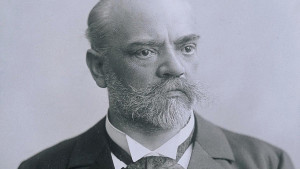

Brahms’s familiarity with late Renaissance and Baroque works came through study and conducting Bach Cantatas, works by Schütz, editing Couperin, and his analytical marks inside his copies of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. Of equal significance was Brahms’s contact with social subcultures that were condescendingly written off as nationalistic elements. Hungarian refugees who arrived in Hamburg during Brahms’s childhood aroused his curiosity. As a youth, Brahms poured out tunes inside a rugged port tavern, a milieu for music that the bourgeoisie class would shun as being at a low culturally unacceptable level. As a Czech, Antonin Dvořák

bore the status a second-tier subject within the Habsburg Empire. His earliest letters to Brahms carry a servile tone, mandatory when one addresses someone of a higher social rank. Brahms’s actions to ensure Dvořák’s continuation as a composer led him to offer his life savings as support for Dvořák and his family, one free of financial concerns , if they would become permanent residents in Vienna: Dvořák turned it down, wishing to remain in Prague. As soon as Dvořák completed a string quartet and symphony during his American sojourn, Brahms pleaded for and obtained the manuscripts, acting as proofreader and aiding in their publication. The proclivities of Austria’s second-class citizens endowed Dvořák’s music with an originality that attracted Brahms to implement them as a desirable edge, one reined in by the status quo. Henry Krehbiel commented on the way nationalistic elements make for grandeur and originality in Dvořák:

Like tragedy in its highest conception, music is of all times and all peoples; but the more the world comes to realize how deep and intimate are the springs from which the emotional element of music flows, the more fully will it recognize that originality and power in the composer rest upon the use of dialects and idioms which are national or racial in origin and structure.

The answer [to the cry for new directions in musical development] has come from the Slavonic school, which is youthful enough to have preserved the barbaric virtue of truthfulness and is fearless in the face of convention. Its characteristics are rhythmic energy and harmonic daring. Like most 19th-century composers, he felt that it was appropriate for music to reflect national characteristics and something almost intangible about its locale. The second point, which many of his colleagues found a bit more contentious, was that this American school of music ought to be based on Negro melodies. Both issues will be dealt with in further annotations. We also might note, though, that Dvořák had a definite interest in his Black students. This may have been related, in part, to his belief that poor students often make good students (he once stated that wealthy pupils do not have the drive to undergo the proper rigorous musical training) and also to his belief that many Blacks were innately musical.

Leaving Freund and Dvořák, we encounter direct evidence of the composer himself as a crucial and overlooked piece of sonic evidence has come to light in some forty-five seconds that are finally audible through a recent advances in restoration technology. These slighted moments had concluded the sole wax cylinder recorded by Brahms in 1889 for Thomas Edison’s agent who was roving Europe to take down spoken statements by notables on the newly invented machine. Vexed over a delay, the peeved Brahms opted to play and began with his G minor Hungarian Dance. Experts past and present refer to it as the sole recording yet he played a second work, unmentioned, possibly for its being off-topic as it wasn’t an original work but merely his improvising on Josef Strauss’ Libellule [dragon-fly] polka-mazur. A light-classical form finds Brahms generating rhythm in a way that solidified during his stint as a tavern pianist. One observer of his playing was the cellist Heinrich Grünfeld, who had partnered Brahms in chamber music: “It is very noteworthy that Brahms, a pianist of the first rank, was in his pianistic performance always cold. That is all the more striking, as his compositions are all full of the warmest life.” Brahms’s pulsating and phrasing resembles the cool exterior of Jelly Roll Morton and in this case, Brahms’s own playing is more Harlem than Habsburg.

Inspired developing musicians were fascinated by Brahms’s disregard of 19th century conventions as his shunning of current trends led to a latent structural modernism that culminated in Schönberg. Along with Brahms’s own pianism we finally hear their spoken, written, and sonic accounts of along with examples of their own, all developed under his guidance. For Ilona Eibenschutz (1872–1967)

“there was still a greater unforgettable pleasure for me, when in the summer of 1892 [at age twenty], one day after dinner, Brahms said: ’Oh! I want to play you – well, a few exercises – which I have just composed.’ (Only Prof. Wendt and my sisters were present, but he would not allow them to enter the music-room, and they had to listen outside on the stairs.) He just tried the pianoforte, and then began to play the g minor Ballade, Intermezzo, Rhapsody in E flat; in fact all the Klavierstücke, Op. 118 and 119! He played as if he were just improvising, with heart and soul, sometimes humming to himself, forgetting everything around him. His playing was altogether grand and noble, like his compositions. It was, of course, the most wonderful thing for me to hear these pieces, as nobody yet knew anything about them. I was the first to whom he played them.”

Eibenschutz’s recording of the Ballade in g minor, Op. 118, no. 3 dates from 1903, six years after Brahms’s death: Eibenschutz, who heard its first performance from manuscript, treats it as new music.

The oldest recorded pianist linked to Brahms is Marie Baumayer (1851-1931),

who left a one-sided four-minute recording made in Vienna, c.1910 of a Schumann Pedal Etude. Its characteristic polyrhythms bear the unmistakable stamp of Clara Schumann’s teaching. Baumayer shapes the piece as chamber music by means of voicings interacting throughout, stylistically identical with the playing of Carl Friedberg and his trio, also heard in this compilation. Soon after Brahms became attached to the affluent and eminent Wittgenstein family, he recommended Baumayer to become their household musician and childrens’ piano tutor. A biographical article places Baumayer’s origins in Celje, Southern Styria, a region where, according to Hanslick [1899], “Slovenian and German elements mixed.” When nearby Graz could offer her little more, she moved to Vienna to study piano with Julius Epstein, who was an influence on the great pedagogue Theodor Leschetizky. Next came studies under Clara Schumann, with whom she had a close and warm life-long friendship. Brahms soon entered her life and she gave important performances of his Op. 99 Cello sonata with Hausmann. Baumayer was one of the few who took on the challenge of Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto, and was its first female interpreter. After her Graz performance in 1882, Brahms commented to his friend Heuberger that “Baumayer is too musical to be a female piano player. To be that, you must be tone-deaf, like [Sophie] Menter [painted by Repin] and others.”

The Wittgensteins dwelled in a Viennese palace.

Their family papers conserve rare glimpses of Baumayer, if scant praise. Although she served as a piano tutor, outside the house Baumayer was among the finest musicians at large in the capitol. Bertha Wittgenstein’s diary and letters [Brahms in the Home and the Concert Hall. ed. Hamilton & Loges. Cambridge 2014], has an entry for 13 November, 1896: “So now, yesterday Brahms was here and was unusually pleasant to her [italics mine]; we had invited Frl. Baumayer as well and Brahms was extremely nice to her [italics mine]. In our stairway the railings had been painted, and Brahms came in covered with paint.” As Brahms acclimated to Vienna and gained the Wittgenstein’s financial support he succeeded in providing a means for Baumayer and led her into his own circle of musicians. Right after Brahms’s death, Hanslick writes: “Marie Baumayer is one of those pianists who stand on their own initiative in the second row, but still occupy the first place through their achievements. In the artistic area of Vienna, Brahms is their domain. It almost seems as if Marie Baumayer’s educational background, as it came to music, one that spread more and more powerfully within her, was but a prelude to its intimate relation to Brahms and Brahms’s music. And now, after the master’s decease, she cultivates with loving hands his memory and this diminutive, nimble young lady with eyes sharp peeking in which wit and kindness appear in turn, such as rain and sunshine, need only to appear, to call Brahms’ living image to mind.” Die moderne Oper, vol. VIII p.192 [1899]

Edith Heymann (1872-1960)

entered into Brahms’s ambit thanks to her studies with Clara Schumann in 1894. From a journal containing notes of her lessons, one that she handed over to her colleague Percy Grainger in 1950, closes in on the music-making characteristic of Clara Schumann and Brahms. Her sole-surviving illustrated radio talk leads us directly into Clara Schumann’s domain. Heymann detailes Clara’s lessons:

2 October 1894 [Bach WTC Book I:] 2nd prelude and fugue, attention to fingering at the end and not too much ritard; the runs after the presto to be played like improvisation; in fugue, theme to be played quite even in tone no shading, special attention to touch, soft and yet firm; no octaves to be used at the end and piano; asked me to learn it by memory, if possible.

30 October 1894 . . . asked me how long I practiced, l said six hours which horrified Frau Schumann, said four hours was the most she could allow, it was bad for the nerves and dangerous etc. One hour’s sight reading a day she advised, said half an hour’s Bach a day sufficient and yet to learn a fresh prelude and fugue every week and always keep in practice two former ones as well! Perfectly impossible for me to do it in that time; came home very disgusted with myself and knowing it would be quite impossible for me to get through what l have to do in four hours; told me to walk two hours a day (morning and afternoon).

19 March 1895: Played 4 Fantasiestücke again, still not pleased with touch in Des Abends, said I must imagine a picture of each piece and have more imagination, of course a good many faults to find still, but not so bad on the whole, said all those Schumann pieces were living people!

Interpretation of Schumann Piano Compositions

I must begin with emphasizing the fact that Schumann was primarily a poet, and all interpretation must be founded on this. For those who have no poetic imagination or temperamental fire and warmth, the big works of Schumann had better remain closed. Recollections of some Famous Pianists (excerpts):

About Clara Schumann herself I have already said so much and cannot speak of her public playing. She had retired from the concert platform before I knew her. However, she often played to her pupils and her great musical conception of the classics and her husband’s compositions are still fresh in my memory and especially her noble rendering of Bach on the piano. It was so spiritually uplifting and dignified, yet full of warmth and feeling. I never heard anyone since to compare with her in this music.

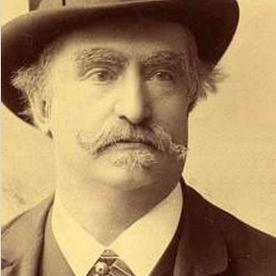

Carl Friedberg (1872-1955)

was taught by Clara Schumann and Brahms. His career started in the late 19th century and spanned the first half of the 20th century. A master musician, his emergence came with a major orchestral debut in Vienna on 2 December 1900 when he played Bach’s D-minor Concerto and Franck’s Symphonic Variations with Mahler conducting the Vienna Philharmonic, the only time these composers were featured during Mahler’s tenure. In 1903 Friedberg played the Beethoven Third Concerto in Frankfurt with Brahms’s colleague Fritz Steinbach, and his substantial concertizing in the following years is chronicled in Germany’s various music journals. A solo evening from 1913 included the premiere of a newly-composed Sonata eroica by Waldemar von Baussnern, who based many of his ideas on Goethe’s writing and stretched his chromaticism almost to the point of atonality. His recital also included the Bach-Liszt Organ Fantasy & Fugue in G minor, Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 90 (a 1949 Kansas City performance is heard on CD I) and various solos by Chopin and Brahms, described as having been “played with incomparable beauty,” the Bach and Beethoven offering “an exquisite pleasure.”

A life of profound experience with central figures of chamber music intensified early on when the teenage Friedberg first met Brahms while serving as his page-turner (Friedberg relates it on CD II). Eugene Ysayë and Friedberg played a sonata evening in 1912, prompting a Cologne critic to write: “Among the soloists, Eugene Ysayë and Carl Friedberg were absolutely first class. The sold-out Gürzenich room witnessed the wonderful artistic dialogue and enthusiastic demonstrations of the listeners that were distinguishing factors of this elite concert.” After World War I Friedberg played in a trio with Carl Flesch and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. He conducted an orchestra with piano debutante Elly Ney as soloist in three concertos, and gave a Brahms evening in Frankfurt (1930) consisting of the C minor Symphony, the B-flat concerto (conducting from the piano) and the Haydn Variations. As soon as Friedberg arrived in the United States he became a highly sought-after teacher, yet his gifts were unappreciated by managers who reduced his engagements.

Friedberg joined the faculty at Juilliard in 1923 and in 1938 he established the Trio of New York

with violinist Danil Karpilovsky (1896-1976) and the remarkable cellist Felix Salmond (1888-1952). Salmond’s formation included a pianist mother who had been a pupil of Clara Schumann and giving the premiere of Elgar’s Cello Concerto. Their ensemble lasted a few seasons and our discovery of two 1939 concert performances brings to light an exalted level of playing chamber music. After Juilliard hired William Schuman to be their new director, one of his first actions was to rid himself of an old man lingering on his roster. Schuman fired off a note in January 1946 to the seventy-three year old Friedberg to let him know that “for the best interests of long-term over-all planning” his services were no longer useful to the school. Friedberg’s biographer Julia Smith writes: “Severance from his teaching positions left him, for the moment, stunned. In the best of health and at the peak of his mental powers, he was regarded by many as one of the greatest teachers in the world. To be counted as old and therefore no longer useful, came to him as a severe shock.” Luminaries of the musical community sent a letter of protest to Schuman that had no effect on his personal decision. Ironically it was a Schumann [Clara] who brought him to mastery, and a lesser Schuman to quash his position.

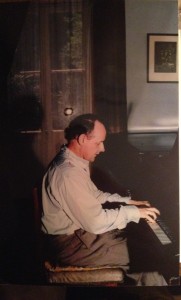

Bruce [Leonard] Hungerford (1922-1977, photo from Cairo c. 1961 at the Tiegerman Conservatoire),

a young Australian pianist, came to Friedberg in 1949 to begin a period of four years’ study with the master. Hungerford, who later changed his first name to Bruce, obtained a portable tape recorder in 1951 and used it to document what Friedberg advised and to gauge his own playing. His lesson tapes allow us all to hear extremely detailed comments as well as Friedberg illustrating on the piano how he recalled Brahms playing his works. Friedberg voices the well-known Rhapsody in g minor, Op. 79, No. 2 in a way that finds its calm middle section revealing itself to quote Bach’s Gigue from the B-flat Partita, an allusion unnoticed until now as we hear it unmasked by Friedberg who witnessed Brahms playing the rhapsody to him and annotatin his music, going beyond the score’s limits. Our booklet for Brahms: Behind the Notes (Arbiter CD 160) describes how these scores were either mislaid, discarded, or perhaps stolen.

Friedberg disliked recording but at age eighty-one was persuaded by his pupil John Ranck to record little over an hour of Brahms, Schumann, and others. The performances Hungerford salvaged also include a Kansas City recital from 1949, which we release in part. Ongoing research involves the Trio’s use of tempi in 1939 and how it compares to metronome markings set down by Fanny Davies during performances she attended involving Brahms as the pianist. Our website’s Music Resource Library contains the comparisons along with audio examples from Hungerford’s lessons [under construction].

One previously unsuspected inheritor of Brahms’s legacy was a Friedberg pupil who developed into a renowned composer and distinguished compelling singer and pianist. Eunice Wayman (1933-2003) “was Friedberg’s only black student but it didn’t bother her and didn’t seem to bother Friedberg either. From their first meeting she understood why his students were so devoted to him. Though he was formal–he almost always wore a suit–he exhibited an obvious and genuine concern for his students’ well-being. Did Eunice have a comfortable place to stay? Did she have enough to eat? Was she able to find a practice room when she needed it?

Eunice felt the same way with Friedberg that she had with Miss Mazzy [the English-born Muriel Mazzanovich]–full of anticipation for each lesson, excited to think about she might learn next. The sessions were similar to Miss Mazzy’s, too.

She found it exciting, too, when she realized she was studying with someone who had a direct connection to one of the masters, given Friedberg’s early work with Clara Schumann. It was as close as she could get to having met Schumann herself.

In her words: “Lessons with Dr. Friedberg were a joy because, although they took the same shape as the lessons I’d always had, he was the greatest musician I had met up to that time and I learned something new each time I sat down to play for him. Every week I played a piece for him to criticize. His corrections were so subtle and delicate that individually each one seemed to make hardly any difference at all, but when I played the piece again and afterwards with all his alterations included it shone like polished silver. Studying under Dr. Friedberg gave me a satisfaction and happiness I couldn’t explain, but I knew this was what I was born to do, what all those hours of practice had been about, and it was leading to my destiny, the classical concert stage.” After her return to Philadelphia she “returned to New York to continue my studies under Dr. Friedberg for as long as possible.” After a move back to New York, Eunice entered into a new social sphere that tied into the music she began composing and performing:

“I was determined to enjoy this life for as long as ir lasted, and when I had time I’d walk around the Village [West Greenwich Village]. . . I made friends with Odetta and I’d see her there and we’d sit [at Rienzi’s Coffee House] and watch the world go by, talk, maybe shop, but usually just relax. I took time to go to museums, picture galleries and poetry readings – I saw [Allen] Ginsberg at a loft reading, didn’t like his poems too much but he was sweet – and generally lived the life I’d promised myself, at least I did between touring across country and going back for tuition with Carl Friedberg.” Her words attest to a reciprocal infusion of inspiration between the high cultures that Brahms resided with and his lifelong attraction to oral traditions and practices that influenced his art. Eunice gained prominence through her voice and pianism, outspoken compositions and arrangements, whose originality was grounded on the foundation and technique that Friedberg imparted to her. Together with Bartók, Wayman continued Brahms’s practices that drew on oral and written traditions, bringing them into a world that knew her as Nina Simone.

Our newly-recovered sounds allow us to get as close to Brahms and his time as possible. We cannot but hope that through them, musicians and listeners who have remained with an incomplete and distorted idea of this daring composer may now experience an intimate contact with Brahms’s artistry from the hands of those chosen by him. Brahms has returned, as a composer of new music.

–Allan Evans ©2015