Disc 1

- Piano Concerto Op. 11 in E minor: I. Allegro maestoso 19:51

- Piano Concerto Op. 11 in E minor: II. Larghetto 9:35

- Fantasie Op. 49 13:31

- Piano Sonata Op. 35 in B flat minor: I Grave. Doppio movimento 6:58

- Piano Sonata Op. 35 in B flat minor: II. Scherzo 5:46

- Piano Sonata Op. 35 in B flat minor: III. Marcia funèbre: Lento 6:41

- Piano Sonata Op. 35 in B flat minor: IV. FInale: Presto. Sotto voce e legato 1:39

- Andante spianato Op. 22 4:03

- Grand Polonaise Op. 22 10:21

Disc 2

First publication of live recordings:

- Prelude Op. 28, No.1 in C 0:41

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 2 in A minor 2:19

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 3 in G 0:54

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 4 in E minor 2:10

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 5 in D 0:33

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 6 in B minor 2:29

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 7 in A 0:50

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 8 in F sharp minor 1:54

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 9 in E 1:20

- Prelude Op. 28, No 10 in C sharp minor 0:28

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 11 in B 0:36

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 12 in G sharp minor 1:25

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 13 in F sharp 3:38

- Prelude Op. 28, No 14. in E flat minor 0:39

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 15 in D flat 5:53

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 16 in B flat minor 1:16

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 17 in A flat 3:07

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 18 in F minor 1:04

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 19 in E flat 1:34

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 20 in C minor 1:23

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 21 in B flat 2:38

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 22 in G minor 0:55

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 23 in F 1:38

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 24 in D minor 2:51

- Berceuse, Op. 57 4:18

- Etude in F, Op. 23, No. 3 1:49

- Polonaise Fantasie, Op. 61 13:47

- Prelude Op. 28, No. 15 in D flat 5:00

- Valse in E minor, Op. posth. 1:38

- Mazurka in C, Op. 56, No. 2 1:45

- Nocturne in F sharp, Op. 15, No. 2 3:40

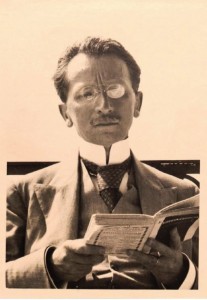

No matter how well one came to know Mieczyslaw Horszowski (1892-1993),

he existed as a quiet, hermetically reserved person who never wasted words or offered entry into his inner life. Horszowski shunned interviews and wrote very little. An ongoing search for his important Chopin performances caused one to wonder what influenced him while he studied the music. His silence could only initiate fruitless speculation over what lay behind his interpretation.

Horszowski’s initial contact with Chopin came through his mother Roza Horszowska, who had studied piano in Lemberg with Karol Mikuli, Chopin’s assistant.

When living in Paris during the 1910s, Horszowski reduced his concertizing to attend Bergson’s philosophy lectures at the Sorbonne and read at length.

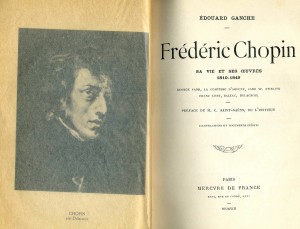

One book from these years was Frédéric Chopin: sa vie et ses oeuvres by Edouard Ganche with a preface by Camille Saint-Saëns (Paris, 1913.)

On examining his copy, we noticed a faint underline in Saint-Saëns’ preface pertaining to Chopin’s style: “fait d’émotion et de simplicité.” Throughout the book a flurry of marginal markings appear aside passages that Horszowski responded to.

While we can no longer ask him about Chopin, a path appeared, as if Horszowski had come back to silently guide us towards what had piqued his interest. A life-long affinity with French was so deep that his wife believed it was the language in which he dreamt. Here follows a clue with later correspondence between Horszowski and Ganche.

–Allan Evans ©2013

Joseph Elsner, Chopin’s teacher in Warsaw, is mentioned in an 1841 article of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik:

He instinctively understood that he faced the founder of a new school of piano playing; therefore he also tried not to restrain his nature, knowing that he was like a pure thoroughbred that must be carefully led and not hampered or trained through trivial means if you sought to shape him.

Ganche quotes Liszt’s comments on Elsner:

“Joseph Elsner taught him the hardest things to learn, the most rarely known: [he taught him] to be self-demanding and to consider the benefits that one only gets by dint of patience and work.” (p.29)

The young Chopin penned his Courrier de Szafarnia, a journal in which he shares impressions of other musicians. He writes on Mr. Better, a Berlin pianist:

In his traits he exceeds Mrs. Lagowska, and it is with this feeling that he plays almost every little note and that seems to come out not from his heart, but from a huge belly. (p.31)

Szafarnia, in the Mazovian countryside, was where Chopin spent early family vacations, a time and place in which he enjoyed a lively social setting with friends and solitude, along with the attractions of folklore. Ganche writes: “His emotivity multiplied his impressions and he plunged himself into that sweet and vague voluptuous melancholy described in Polish as zhal”:

Liszt heard Chopin say to a lady how “he never freed himself from a feeling that has somehow formed, so to say, in the base of his heart, one that is only found in his own language, as no other possessed an equivalent for the Polish word zhal!, one he repeated frequently, as if his ear had hungered for its mere sound, a sonority that encloses all the feelings, producing intense regret, leading from repentance to hatred – the blessed or poisoned fruits of this acrid root.” (p.33)

Chopin writes to Titus Woyciechowski about his Vienna concert on 11 August 1829:

Next to me I had a young man turning my pages who boasted of having performed the same service for Moscheles, Hummel, and Herz. (p.43)

A review in the Wiener Theaterzeitung on 20 August 1829:

His touch is clear but doesn’t shine the way our virtuosi display in the first bars. He plays very quietly, without the bold impetus that generally distinguishes an artist from an amateur. The public recognized a great artist in this young man. (p.45)

At Chopin’s second Vienna recital a critique mentions his new Rondo:

This work, written in a chromatic style, lacks imagination, but there are passages distinguished by their depth and finish of their execution. This young man gives evidence in his compositions of a serious effort to interweave interesting orchestral combinations with the piano.

The Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, 18 November 1829:

The exquisite delicacy of his touch, the indescribable dexterity of his mechanism, the finish of his nuances that reflect the deepest sensibility, the clarity of his interpretation and potent compositions bear the mark of a great genius. (p.45)

Chopin to Woyciechowski on an evening at Princess Wanda Radziwill’s:

All kidding aside, the princess has a truly musical intuition. There is no need to incessantly repeat “crescendo here, then piano, more slowly here, faster there. (p.51)

Schumann comparing Clara Wieck to Mlle de Belleville:

One is a poetess, the other is poetry herself. (p.55)

Chopin to Woyciechowski, (5 June 1830) on Mlle. Sontag:

Isn’t it extraordinary courtliness? Moreover I think it’s so great a vanity that it gives me the impression of a certain naïveté because it’s hard to believe that human nature can be so spontaneous unless you know all the resources of coquetry. (p.57)

Letter of 4 September 1830:

I’ve lost my head. I don’t budge anymore. I don’t have enough strength to fix the departure date. I think that if I leave Warsaw, I’ll never again see my home, I think I’ll die far away. Ah! What sadness to die alone in the milieus amongst the unknown, to see about me unfamiliar faces, instead of the sweet features of one’s own! . . .A man is rarely happy. If he’s destined for short hours of happiness, why should he renounce his illusions, which are also fleeting. (p.58)

18 September 1830:

Be sure of one thing, I beg of you, that I too am concerned about my well-being and that I’m ready to sacrifice everything for the world, [ready to sacrifice all so that] this public opinion, which weighs so much among us [and is so important for us], doesn’t contribute to my misfortune. Not to this intimate suffering [mon malheur] that we hide inside ourselves, but to what I would call our outer misery. Indeed, the world often considers a man to be unfortunate who has worn clothes, a deformed hat, and shoes with holes. (p.59)

Chopin to Jean Matuszynski, 1 January 1831:

I would die for you, for all of you! Why am I doomed to be here alone and abandoned? You can at least confide in your pain and comfort yourselves … How often will my piano moan … I kiss you once again. You go off to war, come back as a colonel. Hopefully everything will go well. Why cannot I at least be your drum? (p.70)

28 August 1830: Piano concerto no. 1 reviewed in Flora::

The composition is brilliant, well written, yet lacking anything particularly new except in the Rondo: its main idea and middle section offer a special charm [spell] through the combination of a melancholic trait with a whim. Probably no one has better understood how to combine the national character in folklore with the style of a brilliant piece than Bernhard Romberg (cellist), whose compositions of this kind exerted a great appeal through the mastery of his playing. Mr. Chopin’s imagination was entirely in this style and he received unanimous applause. (p.77)

Chopin on the police and demonstrators heard outside his apartment (1831):

I cannot tell you the unpleasant impression made on me by those horrible voices emanating from the rioters and that malcontent rabble. Everyone fears that the tumult shall resume tomorrow. (pp.85-6)

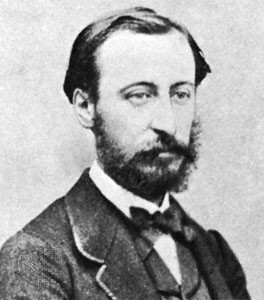

Saint-Saëns on his teacher Camille-Marie Stamaty:

Stamaty was Kalkbrenner’s best pupil and a propagator of his method, based on the guide-mains device that he had invented. This explains why I was put onto its regime. Nothing is more bizarre than the preface to Kalkbrenner’s method, in which he describes the genesis of its invention. The guide-mains was a bar [made out of metal] placed before the keyboard, on which the forearm rested, so as to eliminate any muscle action other than the hand’s. This system is excellent when it comes to train a young pianist to play works written for the harpsichord and on the earliest pianos, whose keys would speak without requiring effort: it is insufficient for modern works and modern instruments. However, this is how one should begin, by developing the strength in the finger and wrist flexibility, and then gradually adding forearm and arm weight to the playing… Not only did Kalkbrenner’s method allow you to acquire that very firmness of the fingers, but it also was a research to produce decent tone quality by the fingers alone, a valuable resource that has become rare in our time. (footnote lists this as an excerpt from his article Souvernirs d’enfance. Revue musicale. 15 March 1912.) (p.89) (photo below: Saint-Saëns)

Schumann on Chopin’s op. 2:

Here it seemed as if eyes, strange to me, were glancing up at me – flower eyes, basilisk eyes, peacock’s eyes, maiden’s eyes; in many places it looked yet brighter – I thought I saw Mozart’s La ci darem la mano wound through a hundred chords, Leporello seemed to wink at me and Don Juan hurried past in his white mantle. (p.101)

Letter to Woyciechowski:

Above all else I hate to hear my doorbell ringing as I’m writing you. (p.103)

LIszt observes Chopin at the Rothschilds’ salon:

The whole of his person was harmonious, Liszt acknowledges. His look more spiritual than dreamy; his gentle and amiable smile did not become bitter. The delicacy and transparency of his complexion seduced the eye, his blond hair was silky, his nose lightly bent. Chopin’s gentlemanly bearing and dignified appearance were of such an aristocracy that everybody involuntarily treated him as a prince. His gestures were graceful and manifold, the timbre of his voice always soft-spoken, often choking, his stature quite small, his limbs frail. (p.105)

Ganche on John Field, developer of the nocturne:

We do not know Chopin’s opinion of Field, contrasted by Field’s, which declared that Chopin was a sickroom talent. (p.109)

Hector Berlioz on Chopin:

I cannot better define Chopin than to say that he embodied an enchanting trinity. His persona, his playing, and his works went so well together that it seemed no one could have separated them, as in the way of the many varied features on the same face. (p. 113)

Chopin on hearing his pupil Gutmann play his Etude in E, op.10/3:

“Oh! Ma patrie!” (p.121)

The truth is elsewhere: after this concert and that of Berlioz’s, Chopin was received rather a bit coldly by the public. (p.132)

Chopin’s sister Isabelle describes his mazurka:

It was played all evening at the Zamoyski’s ball, and Barcinski, who heard it there with his own ears, said they were extremely satisfactory for dance. What do you say to see yourself so profaned, because, strictly speaking, it is a mazurka for the ear rather than for dancing. (p.135)

6 October 1835: Mendelssohn on Chopin, to his sister Fanny Mendelssohn

I experienced extreme joy to finally encounter a genuine musician – not one of those half-virtuosos or half-classics always ready to impose on music “the honors of virtue and pleasures of vice.” (p.146)

In Princess Belgiojoso’s salon,

a lady who had listened to both pianists at a concert given to benefit the Italian poor had this retort: “Thalberg is the top pianist in the world.” “And Liszt?” someone asked. “Liszt! Liszt is the only one!” (p. 147)

Heinrich Heine on George Sand:

She is the greatest woman writer in France and a woman of remarkable beauty. The author of Lelia has calm soft eyes that remind us neither of Sodom or Gomorrah. . . her lower lip, which droops somewhat, indicates exhausted sensuality. Her chin is full, yet beautifully formed. Her shoulders beautiful, even magnificent, as are the arms, and also the hands, which are extremely small like her feet. (p. 192)

Heine on Chopin:

His fame is of an aristocratic kind; his glory perfumed by the praises of good society, and is himself as distinguished as his person. . . He is not merely a virtuoso but quite a poet; he can reveal to us the poetry that lives within his soul; he is a poet musician and nothing compares with the pleasure he brings us as when he improvises on the piano. (p. 194) Out of respect for Chopin who loved George Sand, it is better to dismiss this letter full of calculated reasoning and ill-sounding confidences. (p. 195)

Schumann on Chopin’s works:

So delicate in form, with a cantilena running from the arrival to the end in a charming working out with figuration of all types – it is such a genuine impromptu [Op. 29], not any more or less, so that no other single composition by Chopin can be compared to it. [Scherzo Op. 31.] may be compared without harm to a poem by Lord Byron: Chopin’s Scherzo is as fine, as bold, and displays the same mixture of love and contempt. But without a doubt, it is not for everyone. (p. 201)

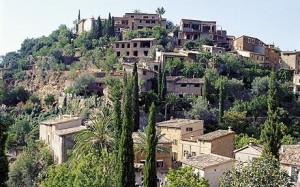

Chopin to Fontana from Majorca:

I could live, dream, and write in the cell of some old monk who might have had more fire in his soul, but which, for lack of use, had to hide and stifle it.

I’ll never forget a certain side trip to a canyon where, in turning, one could make out on a mountain top one of these lovely Arab maisonettes that I‘ve described, half hidden in the snow-shoe of its prickly pear, and a large palm tree that leans over the abyss, outlining its silhouette in the air. When the sight of Paris’s mud and fog casts me into animosity, I close my eyes and I see again like a dream these verdant mountains, tawny rocks, and that solitary palm lost in a pink sky. (p. 211)

Ganche: On the arrival of George Sand and Chopin in Palma, the charterhouse had as its local inhabitants a chemist, a sexton, and a sort of woman-in-command named Maria Antonia, who cheated visiting guests passing through this place. . . The oldest cloisters in Palma contained a cemetery in which each tomb was hardly noticeable by a bulge in the turf. Other buildings completed this vast complex whose loneliness was striking. . . The very uneven and very dusty ground of the cell was covered with Valencian mats of long straw that resemble a grass yellowed by the sun, and the lovely skins of long-haired sheep, of a delicacy and admirable whiteness, so well-prepared in the town. . . The Pleyel piano, wrested from the hands of customs officers after three weeks of talks and a duty of four hundred francs, filled the high resonant vault cell with a magnificent sound. (p. 213)

Divine nature is certainly quite lovely, but one shouldn’t have anything to do with men, not at the post, or on paths. Here’s the reason, dear Jules, why there isn’t a single Englishman here, not even a consul. (p. 216)

28 December 1838 Chopin to Fontana:

I do not remember to have left behind any debts. Anyway, as I say, we will be all clear within in a month at most. Tonight the moon is marvelous; I’ve never seen it more beautiful. . . Under its eye one feels penetrated by a poetic feeling that seems to emanate from everything here. No one has yet scared away the eagles that soar every day over our heads. (p. 217)

George Sand: Our poor Chopin is always very weak and very ailing. It’s rainy here, beyond imagination; quite a terrible flood! The air is so slack, so soft, that he can’t help but drag along; he is truly sick. Fortunately Maurice [Sand’s son] is feeling wonderfully well; his mood only fears the frost, something unknown here. But little Chopin is overwhelmed and coughs a great deal. . . When I lift my nose, it’s to glimpse, through my cell’s window, the moon shining amidst the rain onto the oranges, and I don’t dwell on it for long… Amidst all Chopin’s warbling goes on its own and the cell walls are quite astonished to hear it. (pp. 218-9)

I am embarrassed to tell you how long I will still remain here. This will depend little by little on Chopin’s health, which is better since my last letter, but here he still needs the effect of a mild climate. This effect is not seen and felt soon enough, for a health so rundown. He’s revived with the help of the Palma Consul’s cook, but often their bread arrived changed into a sponge, and the provisions deteriorated due to the rain. Not seeing [Sand & Chopin] come to church, the peasants label them as “Pagans, Mohammedans”, and the mayor pointed them out to the disapproval of his constituents and all importuned on them for their every need. (p. 220)

For him the cloister was full of terrors and ghosts, even when he was in good shape.

It’s there that he composed the most beautiful of those short pages he modestly titled preludes. They are masterpieces. Several induce visions of dead monks and the sounds of dirges that beset them, others are melancholic and mellow; they came to him in hours of sunshine and health, with the noise of children’s laughter under the window, the distant sound of guitars, the warbling of birds under the humid foliage. Still others are of a bleak sadness, and, as they charm your ear, sadden you to the heart. (p. 221)

Sand, in Histoire de Ma Vie:

Liszt thought the eighth [Prelude] in F# minor could also give the impression that seems to have been better translated in the fifteenth Prelude in Db major.

With an exaggerated feeling for details, the horror of the misery and the needs for a well being refined man, Mallorca naturally assumed a horror after a few days of illness …That was his disease. His spirit was skinned alive; bent like a rose petal, a fly’s shadow made him bleed.

Ganche: The same boat that brought them took them back and they had to endure a voyage in an air tainted throughout by a cargo of live pigs. (pp.222-23)*

*Sand’s text provides more details: “We traveled in the company of a hundred pigs, whose ceaseless grunting and unbearable stench left neither rest nor breathable air for our patient. Chopin arrived at Barcelona spitting basins-full of blood and crawling along like a spectre.”

25 April 1839 Chopin to Fontana:

Did Miss Wieck [Clara Schumann] play my Etude well? Couldn’t she have chosen something better than that etude, the least interesting for those who are not aware that it is for the black keys [Op. 10, No. 5]? It would have been better had she played nothing at all. (p. 233)

Late August 1839 Chopin to Fontana:

A pearl color pleases me because it’s neither bright nor vulgar. Thank you for the valet, as he is a great necessity. (p. 239)

Ganche: Although George Sand only mentions Chopin’s living room, his apartment had several very elegantly furnished rooms. Chopin loved flowers, adored pleasing objects, and knew how to ornately decorate its interior with taste. (p. 279)

Part of the dialog is implausible and contrary to Chopin’s usual reserve. In his contacts Lenz wants to take advantage, has to be witty and sometimes his criticism is bad. (p. 281)

Delacroix on Chopin:

The master knows well what he is doing. He laughs at those who pretentiously speak of people and things by means of imitative agreement. He does not know this puerility. He knows that music is a human feeling and human manifestation. It is a human soul that thinks, it’s a human voice that expresses itself, when “surrounded”, attacked so to speak by his emotions, conveys and expresses them through his feelings. He does not have to define what causes him to feel, for music is beyond that. Therefore, music cannot specify them, it does not pretend to. Here is his greatness: in no way could it ever speak in prose. (p. 287)

12 December 1845 Chopin to his friends:

Right now I would like to conclude a cello sonata, a Barcarolle, and something else that I don’t yet know what to call*, but I doubt that I shall have time now because a rush is under way.

*Chopin is undoubtedly speaking of the Polonaise-Fantaisie, Op 61, completed in 1846. [Horszowski underlined its title in the footnote.] (p. 316)

Ganche: He had ash-blond hair, almost auburn, brushed to the back, lively eyes, a charming smile, neatly defined features, a long and slightly arched nose.

Once at the piano, Chopin played to exhaustion from an unrelenting disease, his eyes circled in black, his glances enlivened by a feverish light, his purple lips turned to a bloody red, he grew short of breath! He felt, we all felt something that did not have the strength to hold back! The fever that burns him pervaded us all!

Yet one had a sure way to wrench him away from the piano: it was to ask him for the Funeral March that he composed after the disasters in Poland. He never refused to play it, yet the last measure hardly sounded when he would reach for his hat and leave. This piece, which was like a song of agony for his country, made him take it too hard and he could not say anything afterwards because this great artist and great patriot and the proud notes that burst in his Polonaises tell all that is vibrantly heroic behind the pallid face. (p. 321)

Georges Mathias saw him get into a rage due to a fermata placed by Liszt in his transcription of Adelaide, “culminating terrible flatness, a stain made by Liszt onto Beethoven’s wonderful cantilene.” (p. 327)

His creation was spontaneous and miraculous, says George Sand in her Story of My Life. He found it without seeking, unpredictably. It came to him on his piano, suddenly, complete, sublime, or it sang in his head while taking a stroll, and he was in a haste to hear it by throwing himself onto the instrument. . . He spent six weeks on a page, only to return to the writing he traced on its first draft. (p. 330)

Chopin’s style was distinguished also by simplicity and a regularity of movement. (p. 334)

Liszt on Chopin’s rubato:

In his playing, Chopin ravishingly renders this trepidation, for which he always has the melody undulate like a skiff on the breast of a powerful wave. (p. 335)

Ganche on Chopin’s unfinished Piano Method:

The master was concerned with refinement of touch and good hand placement. He advised beginning with scales in B major. . . Stiffness exasperated him and during a lesson he repeated: “Easily, easily.” (p. 342)

Mme. Streicher on Chopin’s playing:

His playing was always noble and beautiful. . . He took much trouble to teach the student how to play legato and cantabile. “He (or she) does not know how to tie two notes” was his most severe criticism. He demanded attention to rhythm and hated languors, delays, rubatos displaced as exaggerated ritardandos. (p. 349)

Ganche: The writer seems to have wanted to analyze her own situation and – can’t you tell? – as she categorically indicates Chopin. Whatever her intentions, her relationship with Chopin and their individuality offer material ready for a novel, and George Sand often took models from the people around her. Pauline Viardot served for Consuelo and Beatrix by Balzac was written after her indications and observations on Liszt and the Comtesse d’Agoult. “This is about Liszt, and Madame d’Agoult she gave me the subject for Convicts, or Amours forcées that I’ll do, Balzac wrote to Mme Hanska, because in her position she cannot do it.” Balzac found Convicts too fierce a title for its characters and replaced it with Beatrix.

In one of his letters to Henry Laube in 1850, Heinrich Heine wrote about George Sand: “She has outrageously abused my friend Chopin in a detestable divinely written novel.” (p. 355)

Sand, in Lucrezia Floriani:

It was something like one of these ideal beings, created in the poetry of the Middle Ages to adorn Christian temples; an angel, beautiful face, like a tall, sad woman, pure and slender, as a young god of Olympus, and to crown an assemblage, an expression both serious and tender, and passionate. (p. 357)

19 April 1847: Chopin

If you do not respond to a letter at once, you can’t get started, and your conscience, instead of the paper attracting you, your conscience pushes you. (p. 368)

10 February 1848: Chopin

She plays the actress at Nohant in her daughter’s bridal chamber; she tries to forget and deadens her feelings as best she can. She will not wake up until her heart begins to hurt – that heart, which at present is dominated by the head. (p. 384)

Ganche: In the Polonaise-Fantaisie, Chopin deviates beyond the Polonaise’s form and distinctive rhythm. He retains all of his freedom of expression and aims to tragically translate the despair of a defeated nation. In the same thought, Chopin seems to associate his own sorrows with those of his country. The Polonaise-Fantaisie is a sublime song of agony, at the same time painful and heroic. “It seems to me so touching!” said C. Saint-Saens: “Discouragement and disillusionment, regrets, leaving life, religious thoughts, hope and faith in immortality, he expresses all this in an eloquent and captivating form.” (p. 391)

Chopin’s music is the music for those who comprise mankind’s elite, through intelligence and the heart. (p. 392)

Jane Carlysle to Jane Stirling:

I never liked any music so well—because it feels to me not so much a sample of the man’s art offered “on approbation” (the effect of most music for me) but a portion of his soul and life given away by him—spent on those who have ears to hear and hearts to understand. (p. 401)

18 Aug 1848: Chopin to Fontana in London

But the real trouble is this: we are the creation of some famous maker, in his way a kind of Stradivarius, who is no longer there to mend us. In clumsy hands we cannot give forth new sounds and we stifle within ourselves those things that no one will ever draw from us, and all for a lack of a repairer. I can scarcely breathe: I am just about ready to give up the ghost. And you, I am sure, are growing bald: you will hang over my tombstone like one of those willows at home – do you remember? – that display their bald pates. (p. 403)

3 November 1848: Reference by Ganche to a letter from London

He has neuralgias, he breathes with difficulty and his servant Daniel dresses him and carries him like a child. (p. 407)

“They are all in agreement on climate, calm, rest,” he wrote to Solange Clésinger. “As for rest, I will have it one day, without them.” (p. 409)

10 April 1849: Delacroix’s journal

He told me that he could always busy himself with something, with something so trivial, a task to fill these moments and help him forget these vapors. Real grief is another matter. (p. 411) [see below.]

Ganche: Did Chopin still think of George Sand? Only Franchomme claimed to have heard him stammer: “She told me that I would die in her arms.” (p. 416)

Rest in peace beautiful soul, noble artist! Immortality has started for you, and you know better than us where we end up, after the sad life of this world, great thoughts and high aspirations. (p. 421)

Jane Stirling:

The genius of Chopin is the deepest and most full of feelings and emotions that existed. He gave speech to one instrument, the language of the infinite, he often summed up in ten lines that a child could play poems of huge elevation, dramas of energy without equal. He has never needed major material resources to give the word of his genius. It took him no saxophones or ophicleides to fill the soul with terror or church organs or human voices to fill one with faith and enthusiasm. He was not known and the crowd does yet not know it. It is all three together, and he is still himself, that is to say loose in taste, more austere amongst the great, more tearing in pain. Only Mozart is superior to him only because of his undisturbed health and as a consequence a fullness of life. (p. 425)

Ganche: Very different from the classic school accompaniment, said Elie Poirée [1850-1925, early Chopin scholar], is Chopin’s accompaniment of the melodic phrase that Chopin achieved by using chords, arpeggios that oscillate, mounting or descending freely onto the sound scale into an amorphous area where it is raised, isolated, an ideal voice, that of a skilled improviser’s and inspired. Through his choice of these chords and above all, their placement of the simple accompaniment, they release a harmonic atmosphere that elusively floats around the melody, enveloping and penetrating it entirely. (p. 427)

Liszt on Chopin:

The little groups of upper notes, falling like light drops of dew upon the melodic figure. This species of adornment had hitherto been modeled only upon the fioritures of the great school of Italian song; the embellishments for the voice had been servilely copied although become stereotyped and monotonous. He imparted to them the charm of novelty, surprise, and variety, unsuited for the vocalist, but in keeping with the perfect character of the instrument. (p. 428-29)

Ganche: George Sand burned her correspondence with Chopin. (p. 435)

Delacroix’s portrait of Chopin is remarkable. His face is contorted with pain and bears stigmata of the disease that was undermining Chopin and reflects all the agitations of his soul.

Letters from Edouard Ganche:

- Edouard Ganche

Ganche and Horszowski began to correspond some ten years after the pianist read Ganche’s biography. He edited Chopin’s piano works* and shared his research and discoveries 1922-1932. Bice Horszowski Costa uncovered Ganche’s letters to her husband and provided their translation.

12 October 1923:

My Chopin collection has grown with very important pieces in July. I have “Frederic Chopin on his Deathbed” by Clesinger, an admirable piece. An unknown pencil portrait of Chopin by Winterhalter mounted onto a screen. This portrait, given to me by the heirs of Jane Stirling, was made two years before Chopin’s death and is splendid. A silver perfume burner (brule parfum) in the style of Louis XVI that was always in his room: Tellefsen’s daughter gave it to me for my wedding. A Russian painter Yvan Thiele made a painting based on the documents I gave him, two colored etchings that represent Chopin at the piano, and the other a bust, which is better. I also received Chopin’s hand cast from Hungary, etc.

Last week I spoke with Maurice Ravel and mentioned your name to him.

26 March 1929:

I now have the greatest collection in the world (as the Americans say) of Chopin. I mention the most beautiful piano owned by Chopin, the only one signed by him and that Jane Stirling possessed. It’s in great condition. My collection is in Lyon and I have one foot in Paris and the other in Lyon. . . We often speak of you and I would wish very much if you could spend a day in Lyon. All of us being gourmets, we would prepare a succulent dinner in your honor and you would visit my Frederic Chopin museum. It’s worth the trip I assure you. I work fifteen hours a day to finish my work without being able to do one tenth of what I wish to accomplish [Ganche’s forthcoming edition].

3 Sept. 1932 (Lyon):

Dear Friend,

I take the liberty to recommend the edition ordinaire of Chopin’s works in three bound volumes*. In its different formats the edition is splendid and arouses general admiration – paper, print, everything is superior: “This is a first class document,” M. Alfred Cortot wrote to me. There is a list of the errata that will be corrected in the next printing. [Ganche attached the errata.] I would be happy to know your judgment of this edition. Would you come to Lyon in November? It will be mainly busy with moving Chopin’s ashes to the Wawel [castle in Kraków].

*Chopin. Les Oeuvres complètes pour piano. Oxford University Press. Preface in French, English & German.

Eugene Delacroix: Journal entry of 7 April 1849

Went with Chopin for his drive at about half-past three. I was glad to be of service to him although I was feeling tired. The Champs-Élysées, l’Arc de l’Étoile, the bottle of quinquina [aperitif of bitters], being stopped at the city gate, etc.

We talked of music and it seemed to cheer him. I asked him to explain what it is that gives the impression of logic in music. He made me understand the meaning of harmony and counterpoint, how in music, the fugue corresponds to pure logic, and that to be well versed in the fugue is to understand the elements of all reason and development in music. I thought how happy I should have been to study these things, the despair of commonplace musicians. It gave me some idea of the pleasure that true philosophers find in science. The fact of the matter is, that true science is not what we usually mean by that word – not, that is to say, a part of knowledge quite separate from art. No, science, as regarded and demonstrated by a man like Chopin, is art itself, but on the other hand, art is not what the vulgar believe it to be, a vague inspiration coming from nowhere, moving at random and portraying merely the picturesque, external side of things. It is pure reason, embellished by genius, but following a set course and bound by higher laws. And here I come back to the difference between Mozart and Beethoven. As Chopin said to me, ‘Where Beethoven is obscure and appears to be lacking in unity, it is not, as people allege, from a rather wild originality – the quality which they admire in him – it is because he turns his back on eternal principles.’ Mozart never does this. Each part has its own movement which, although it harmonizes with the rest, makes its own song and follows it perfectly. This is what is meant by counterpoint, punto contrapunto. He added that it was usual to learn harmony before counterpoint, which is to say to learn the succession of notes that leads to the harmonies. In Berlioz’s music, the harmonies are set down and he fills in the intervals as best he can.

Those men, who are taken up with style that they put in before everything else, prefer to be stupid rather than not to appear serious. Apply this to Ingres and his school.

translated by Lucy Norton