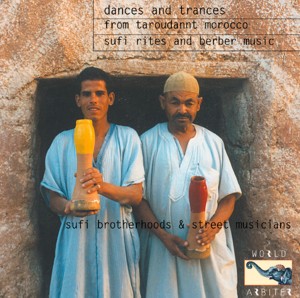

Track List

- Adhan For Early Morning Prayer (salat as-soudh)

- First Guerrera

- Second Guerrera

- Guerrera perfomed by men

- Combined adhans for salat as-soubh

- Egyptian style song with oud

- First song performed by Berber street musicians

- Second song performed by Berber street musicians

- Hadra (followed by adhan for night-time prayer)

Dances and Trances

The city of Taroudannt, Morocco, is surrounded by perfectly-preserved red-ochre mud walls dating back, in part, to the sixteenth century Saadien dynasty, which chose Taroudannt as its capital before moving to the larger and more accessible Marrakesh. While the walls and their ramparts are impressive, the real attraction of Taroudannt lies in its purely Moroccan character, which has remained essentially unchanged for centuries. Situated in the Souss River valley and cut off by the snow-capped peaks of the Haut-Atlas mountains to the North, and the semi-desert Anti-Atlas range to the South, the French occupiers never created a modern ville-nouvelle here, with the typical unimaginative grid of streets one finds in many cities, large and small, throughout Morocco. The feeling of Taroudannt is timeless and traditional.

Outside the walls through the western gate, hides are tanned using the time-honored method of soaking in vats of animal urine…the nose warns of their proximity. On a side-street, thick black smoke billows from the doorway of the charcoal maker.

The tools of practical magic are found in the souk: dessicated lion skins, snakes and ravens hang in the shops, over great baskets of herbs, lizards, and porcupine quills (used as a sympathetic remedy for impotence). Shelves lining the walls, hold jars of alum (shebba, used as an oracle to discover the identity of one who has worked black magic, and against various evil influences), carbonized wool (smoqh, for ink used to write amulets), cantharides beetles (“Spanish fly”), and numerous other ingredients, animal, vegetable and mineral. Magic practitioners (fqihs) of the Souss are particularly skilled in love-magic, for both good and evil (especially the latter).

Though the valley is seasonally green the landscape can be harsh, the surrounding hills arid and stony, showing tortuously convoluted sedimentary layers, the result of violent geologic activity. The roughness of the setting influences the artistic-religious expression of its people; even the adhan (call to prayer) seems to spring from the sun-baked rocky land. Not singing, but proclaiming with a vital urgency, the muezzin (caller of the adhan) seems to announce the great message of Salvation for the very first time- a cock’s crow to humanity- and eons removed from the graceful melisma called by the muezzins of Arabia, Egypt, and, in fact, most of the Islamic world.

The early morning prayer, salat as-soubh (also known as fajr), may be performed at any time between the very first light of dawn and the first appearance of the sun as it begins to break the horizon. The adhan which precedes this prayer is, therefore, called into the predawn darkness. I did not seek out a barnyard to provide the avian ambience heard on the recording (one simply encounters chickens frequently in rural Morocco), but it does afford a comparison between these two of earth’s creatures, ritually announcing their existence just before the welcome return of the sun. One is almost prepared to imagine that the cock’s crow has provided a stylistic model for the muezzins of the region.

A brief series of introductory chants precedes the adhan proper. Due to the early hour, a special exhortation (line 5) is inserted into the adhan of salat as-soubh, absent in adhans for the other four regular daily prayers:

Allahu Akbar (4 times) * Ash-hadu an la ilaha ill-Allah (2 times) Ash-hadu anna Muhammad-ar-rasoolullah (2 times) Hayya ‘alas-salah (2 times, face of muezzin turned to the right) Hayya ‘alal-falah (2 times, face turned to the left) As-salatu khairum minannaum (2 times) Allahu Akbar (2 times) * La ilaha ill-Allah

Allah is Most Great! * I bear witness that there is no God but Allah! I bear witness that Muhammad is the Apostle of Allah! Come to Prayer Come to Salvation! Prayer is better than sleep! Allah is Most Great! * There is no God but Allah! [track 1]

I arrived in Taroudannt during a punishing heat-wave in the month of August. During the day, and especially between the hours of noon and five o’clock, my chief concern was survival. My friend Hemidann Hassane (known to his friends and family as Hussein) had provided me with a room in the nearby village of Dar El Boura. Electricity had come to the place only weeks before my arrival, and I did have an electric fan in the room, but it merely succeeded in blowing hot air into my face. The minutes passed like the proverbial hours as I waited each day, feeling utterly useless and desultory, for the sun to sink lower, and with it, the temperature.

Hussein and his extended family had left their house in central Taroudannt to spend the summer at Boura. I was an honored foreign guest, and was duly treated with the famous Arab hospitality, or in this instance, Berber hospitality (“Berber” is a name given to the indigenous North Africans by foreigners, and is derived from “barbarian”. Their true name is Amazigh. The language is Tamazight, while in the South, Chleuh, also known as Tashelhait or Soussi, is spoken.)

Hussein’s 15 year old sister Saadia was assigned to my case: she cooked, cleaned, washed my hands and clothes, and generally saw to me. Each morning as I made my way down the pise steps to the courtyard, Hussein’s mother would yell, “SAADIAAA!” The graceful-as-a-gazelle young girl would then appear, bowl in hand, to serve my breakfast. After the meal, she would pour water over my hands, and pass me a towel. Those who have never experienced this kind of feminine attention have no idea how pleasant and seductive it is. When I expressed admiration for the manner in which Saadia was attending to my needs, visions of wedding bells appeared; I noticed that the women, in particular, began to gaze at me with a special tenderness.

I was plied with food numerous times each day…corn soup in the morning, and bread dipped in honey and argan oil during the day. Morocco is the only place on earth where the argan tree can be found. Oil is extracted from its nut in a most peculiar manner. As it would be extremely tedious work to break into the hard nuts to get at the oily seeds, the work is left to the goats, which eat the nuts. The seeds are evacuated in their feces, then recovered by the women of the household, and pressed for the oil.

Evening meals consisted mainly of tajine, a meat and vegetable stew, slow-cooked in the courtyard over a covered clay stove. I could never eat enough to please them:

“Please, Hussein, I have eaten enough for ten people!”

“Good…now eat enough for fifty!”

After a meal, we generally had grapes, picked from the vine which grew thickly along an arbor over the courtyard.

Hussein knew that I was in Morocco to record music during the mouloud (birth) season, the twelfth day of the Islamic month of Rabi’ al-Awwal, the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad [Salalahu aleihi was-salaam!]. He assured me that I would have opportunities to hear much good music; a moussem (annual celebration of a Moroccan saint) was approaching, to be held right there in Boura.

Moussems provide the opportunity for local observance of Moroccan saints. Most are held around mouloud (although others occur at harvest, and follow the solar calendar). It is a time selected specifically to underline the importance of the local cultus as against the wider observance of world-Islam. These mouloud-tide moussems serve a triple purpose. The birth of the Prophet may be celebrated, a local saint may be venerated, with the intention of acquiring his (or her) baraka (holy power), or commonly, as an opportunity to socialize with neighbors from surrounding areas. A market may be held, musicians brought in, and singing and dancing engaged in by all. Moussems, therefore, may be secular, religious, or a combination of both. One fine August evening in Dar El Boura, the courtyard began to fill with people from nearby villages in the foothills of the Anti-Atlas mountains; the women dressed in their most beautiful jellabas and scarves. It turned out that the moussem of a local wali (saint, founding sheikh of a religious brotherhood), one Sidi Nasri, was to be held during the next two evenings. It also turned out that the zaouiyya (religious hospice, place of meeting used by a brotherhood, and devoted to its sheikh) was only about 50 yards from the house, and that Hussein’s step-father was the muqaddem (leader)!

Often, the exact day of a moussem may not be definitely fixed. Logistical or other problems may arise, causing some uncertainty and confusion. As I was making my way back to Dar El Boura on the first night of the moussem, the driver of the car in which I had hitched a ride asked where I was going. When I told him that I was headed for the moussem, he turned to me and gently said, “I am sorry, but you missed it. It was held last night”. He evidently was unaware that the event had been pushed back by one day. There is a lesson in this: In Morocco, and elsewhere, no doubt, never accept important information from only one person! This was a largely secular moussem, more like a two-day music and dance party than religious ritual. The first night afforded an opportunity for the women to actively participate in the music-making and dancing, mixing with men in the musical ensemble in the courtyard. Hussein’s elder sister, Fatima, played a small flat drum of the variety known as tar, and quite expertly at that. She can be heard in the selections recorded that evening. The following night, an ensemble composed exclusively of men would perform, within the open-air zaouiyya. As the musicians played in the courtyard, guests took turns dancing to the lively rhythms. At one point, the young and beautiful Saadia took center-stage and, dressed in a gorgeous yellow jellaba, her new gold necklace around her slender neck, began whirling, jumping and twirling, her arms held over her head, her feet stamping so hard the dust rose from the ground. I was perched on the wall above, microphone in hand. She gazed up at me, to be certain I was taking it all in. I was, Subhan’allah! [tracks 2, 3] (Saadia is now happily married -to a Moroccan- and living in Morocco.)

The Guerrera

As Taroudannt is a gateway to the desert, many Saharan influences can be heard and seen in its music and culture. Both nights of the moussem the featured musical form was the Guerrera (or Gourara), named for the desert town in Algeria which gave birth to it, an isolated oasis about forty miles northeast of Ghardaia.

The most striking features of the Guerrera are its polyrhythms, in septuple and quintuple meters, and its distinctive polychoral hocketing. While the music in the courtyard was beautiful, spontaneous, and affecting, containing all the essential elements of the Guerrera, the men’s performance the next night in the zaouiyya, attended by hundreds, brought the form to its ultimate grandeur, an epic journey through a musical landscape of astonishing novelty, complexity, and intensity.

It began with a series of non-metric introductory verses, first intoned by a soloist, and followed by a choral response. Among the messages communicated in the dedicatory prologue, good wishes were offered to the King, on the occasion of a royal visit to the Western Sahara town of Laayoune. This verse in all likelihood refers to a visit by King Hassan II in 1985, to commemorate the trip made to that place 100 years earlier by his Alaouite ancestor and name-sake, Sultan Moulay Hassan. [King Hassan II has since passed away (1999), succeeded by his son, now King Mohammed VI].

Seemingly without warning, the verses were suddenly interrupted by the hocketing of three groups of singers, as the percussion instruments beat out a dense and driving accompaniment in rapid quintuplets. The hocket rhythms began to impose on the verses more frequently, the musical gestures piling up, each entrance subtly varied, and progressively more active, until a soloist announced the main lyric, in septuple meter, sung in the Chleuh dialect ; it was a love-song:

“W’al habib-ayyazina, libwit rassi bwitulik(aaa).”

“My dear, my beauty, what I want for myself, I want for you.”

The lyric continued in the form of statement and response between two choruses, situated widely apart in the space of the zaouiyya, and separated by episodes of tri-choral hocketing. The nakous, a heavy block of metal played with 2 metal rods, beat out a stream of repeated notes bearing a relation of 5:2 to the pulse of the preceding melody, as the hocketers sang 3 notes to each quintuplet. The drumming motifs were marked by great rhythmic freedom, especially when “shadowing” the moves of the dancers. The effect to the untrained ear was of two completely independent over-lapping rhythmic schemes, each entering apparently at random, a brilliant and complex example of rhythmic ambiguity, which of course was second-nature to the participants. A new, wordless melody, ten beats to the “measure”, was then introduced and passed back and forth between the two choruses at either end of the zaouiyya. The hocketing episodes grew more and more insistent, longer, until the melody was left far behind, never to be heard from again. We found ourselves in…outer space! At a certain point in the extended final hocketing section, the main body of the piece, I became aware that we all were spinning out on a great voyage together. Rising to the surface during a passing moment of objectivity, I wondered, “How did we get here? What has transpired, that we find ourselves swimming in this sea of hocketing? Where did this all begin…? It became a throbbing, living entity, engulfing all present.

“Ah!” was the syllable sung during the hocket sections, with each singer pouring out his soul in every utterance. Some were so transported they could only grunt out their syllables, nearly spent as they were from the continuous high level of excitement. That such intense monosyllabic repetition should lead to a dhikr-like religious state of mind is exemplified by the voice of one hocketer we can hear whose “ah” changed to “al-LAH”.

At last, suddenly, the journey came to an end, to the exclamations of all, uttering deeply-felt praises to Allah and His Prophet. The instruments played during the Guerrera are all percussion, including the long hour-glass shaped tarreja and darbouka, flat bendir and tar, sheep-shears, clapping hands, and the most penetrating of all, commanding the hocket sections, the nakous. Although the nakous produces a steady stream of even notes during the hocketing, they are divided between the hands as follows: llrl rrlr…etc.

In the main section, men emerged from the crowd to jump into the center and dance in a stylized martial fashion, leaping and spinning in the air. At these times, the small high flat drum would follow their movements closely, the sharp slaps timed to coincide with the leaping dancers as they stamped back to earth. After completing his turn, each dancer would run back into the crowd to rejoin his friends, all laughing joyously. [track 4]

City Mosques

Sizable cities have a high concentration of places of worship. In the case of Islamic countries, the adhan is called five times each day from its mosques, at quite specific hours related to the movement of the sun. The result, in a concentrated living area, is a beautiful and bewildering counterpoint of muezzins calling the adhan at more or less the same time, each entering like a new voice in a fugue: their adhans differ according to the stylistic peculiarities of the muezzin. Introductory chanting often precedes the soubh prayer, as in the present example. As our point of “view” is the Place Assarag, we also hear sounds of the town’s center, its pedestrian and vehicular activity, as it comes to life in the early morning. [track 5]

Street Musicians

Morocco has a long tradition of itinerant street musicians, who often provide story-telling in the oral tradition along with their music. In most Moroccan cities, one may find musicians representing all the main styles, including the predominantly northern Arabic, and more wide-spread Berber, as well as representatives of various specialized schools, such as the African-influenced Gnaoua sect. In Taroudannt, I recorded two examples of the many one encounters. The first is a soloist accompanying himself on the oud, the oriental precursor of the lute (Arabic: al-oud, becoming “lute” by dropping the “a”).The song he performs in Arabic is reminiscent of the genre popularized by such Egyptian artists as Muhammad Abdul Wahab, and may have been adapted from the repertoire of that well-known singing film star. Our performer was working in the main square (Place Assarag) in the early evening. [track 6] Also enlivening the Place was a group of five Berber musicians singing and playing percussion, rabab, or amzhad (single-stringed violin) and banjo. When the leader was asked for a translation of their song, he laconically replied “it is about Morocco”. These ensembles often convey political messages through their music. [track 7-8]

Moroccan Saints

Taroudannt’s predominantly Chleuh Berber population follows the ancient rhythms of a life punctuated by the unique rituals of Moroccan Islam. Ortho-practic Islam, throughout the Arab world and beyond, prescribes a sedate existence, spiritually elegant, modest, orderly and controlled. Access to Allah is accomplished through direct prayer. But Allah is remote. He may not be – even fancifully – depicted in Islam. (Islam, in fact, in its strictest form, forbids the depiction of any living thing.) As in virtually all other religions, man finds himself in need of a more immediate connection to the object of his supplications, something he can see, touch, whose essence he may share or come away with. To the pagan, this role may be assigned to a manifestation of Nature, be it a planet, mountain, tree, spring or animal. Among the Moroccan sufi brotherhoods, saints provide this contact. Each brotherhood is composed of the followers of a particular wali. French orientalists have labelled Moroccan saints, together with their domed and whitewashed koubbas (structures, usually whitewashed and domed, containing the tomb of a saint) as marabouts (from the Arabic murabit – a pious man residing at a fortified frontier post to participate in holy war- jihad). Walis have carried much political influence throughout Morocco’s history.

As the tzaddik provided a human intermediary for East-European Jewish mystics, so the wali offers the same for Moroccan Muslims. The Moroccan saints are known to be workers of miracles, specifically, miraculous cures, possessors of the very same power, now Islamicized as baraka (holy power), which drew their ancestors to the aforementioned trees and springs. It is no coincidence that many koubbas are situated in close proximity to sacred natural phenomena around which a cultus was formed and anciently practiced long before the arrival of the saint who superceded, or more accurately, absorbed it. In fact, some saints are thought to be legendary figures who never existed in mundane reality, but emerged from the imaginal world to Islamicize an already-existing natural site.

The Hadra

The baraka once possessed by the wali in life has been passed on and, in death, enhanced. This baraka, which is transferable, resides not only at the koubba, where the air is thick with it, but is also released at any place or time the devotee performs the appropriate ritual. The engine of this ritual is the music, or hadra, which resonates in the individual to bring him (or her, much to the dismay of those who embody the strict conservative mores of normative Islam) to a state conducive to the absorption of baraka, a state generally known as a trance. This power is further activated by a dance which seems to be the natural physical consequence of the music.

Under the influence of Morocco’s saints certain aspects of religious expression became everything that commonly-practiced Islam was not: ecstatic, spiritually violent, immodest, wild….. out of control. Their ritual music may feature the pounding of flesh and sticks against goat skin drums, shouted, screaming anti-melody, blaring and frenzied double-reed ghaitas, accompanied by dancing, leaping, twirling, stamping.

In a state of trance, devotees of the more extreme brotherhoods, such as the Aissaoua and Hamadsha, may wound themselves with axes, eat glass, devour live animals using only their teeth, engage in animal-mimic dancing and grunting, all led on by the irresistible force of some of the most powerful music on the planet. Surely this tendency towards ecstatic catharsis has its roots in pre-Islamic Berber ritual.

It may come as no surprise that the Authorities, representing the “received” Islam of Arabian heritage, do not approve of such practices, and this disapproval has been made manifest in their steady suppression over the course of, mainly, the twentieth century. “It is not Islam”. But heresy only exists, as in all religions, in the eyes of its beholders, its opponents. To members of the tawaif, or local circles of devotees dedicated to a particular sheikh, they act from the very center of Islam. Through their rituals, they give perfect expression to God’s will, as they are the possessors of the One Truth, the Gnosis; how could it be otherwise?

The hadra is essentially a curative ritual, and the baraka acquired as a result of participation may be directed towards a specific condition or illness, or simply for its acquisition. A hadra may be prescribed at any time, and indeed is most often performed as a private ceremony in the home, to benefit an ailing individual. It is especially beneficial at the time of a moussem. The hadras of the Aissaoua are well-known to heal mental infirmities. Insanity is met on its own terms in the wild trance-dances brought on by the hadra. In Morocco and many other areas of the world where ancient traditions survive, life is heavily influenced by powerful unseen entities- djinns (Arabic plural: djnun).

Against the evil among them (some are beneficent) war must be waged at every turn. Djnun are available to inflict every possible variety of malevolence. A djinn responsible for a particular illness, as a result of the possession of the victim, may be reached and driven away through a melody specifically associated with that djinn. On hearing the tune, the djinn is unable to resist its power. In the throes of battle – the hadra – the possessed person exhibits all the signs of the wild struggle taking place in his soul.

Structurally, the hadra consists of introductory verses, the successive statements of musical themes, each at a faster tempo than the preceding, and may conclude with dhikr (from a root meaning “remember”), the ritual repetitive chanting of some form of the profession of the Tauhid (from a root meaning “one”) or Unity of God, La ilaha ill-Allah…”There is no God but Allah,” or other short phrases which may be shortened or transformed.

The participants form either a line or a circle around the musicians and perform the distinctive “limping” dance, while other participants may dart in and out of the inner area in varying degrees and states of abandon. During a hadra at Meknes for the annual convocation of the Aissaoua, a woman entered the circle and began rolling back and forth on the ground: after some twenty minutes she lay motionless, and was later carried out.

The lead musician may run up to a member of the circle to confront him with a violent drum beat. All present are swept away by the power of the music and occasion. (At the aforementioned hadra at Meknes, held in the zaouiyya housing the tomb of Mohammed ben Aissa, venerated by the Aissaoua, I had intended to record the music, but was so “entranced” that I could not push the record button. No one could remain uninvolved or motionless. The impact of this ritual on an unsuspecting foreigner is considerable, especially when accompanied by the acts of ritual self-mutilation for which the Hamadsha in particular are well known; one finds oneself amidst an experience at once utterly alienating and mesmerizing. In his somewhat sensationalized but aptly-titled “Morocco The Bizarre,” George Edmund Holt, the American Vice-Consul General in Tangier from 1907 to 1911, describes what sounds like a meeting of Hamadsha in that city during mouloud :

“…when he hears the interminable beat of the low-voiced drums and the never-ceasing monotony of the shrill pipes [ghaitas]: when he sees the banners of the Prophet, malignant green and red and gold, then [the] Christian foreigner feels that here is something which he cannot understand; that here are a people voicing the ideals of the Mohammedan world, which somehow seems to become suddenly larger, and that he himself has had a mistaken conception of what Mohammedanism means. And when his eyes behold the rise and fall of the glittering axes upon shaven heads of man and boy, and he hears the peculiar rattle of contact between head and weapon, and notes the beginning of the red flood, which gradually spreads down over face and neck and garments, witnesses the ecstasies of pain in the name of Allah, then somehow the sun seems to become unbearably hot, the air stifling, the shriek of the pipes and the beat of the drums simply infernal. And with it all comes just a faint impression of what fear might be, and the desire to get away from it all, for surely this mob of dancing, singing demons is not real.”

The hyperbole (not to mention cultural chauvinism) grows still further in Holt’s account of an Aissaoua hadra at Tangier:

“…one may hear in the distance the rumble of drums, the shrill notes of pipes, and finally the crowd at the lower gate breaks apart and the red and green banners of the Aissawa brotherhood pass through. The music becomes louder, having the free air of the socco [the main square in Tangier] to swell in, half a dozen pipes shriller than the shrillest bagpipes, three or four drums louder than any drums heard on battlefield, shouting, crying, wailing together in an indescribable ecstasy, in which the monotonous repetition of notes seems to focus on one small point all the delirium which uncivilized man has been able to put into his barbaric music.

“And then, worked into a frenzy, come the dancers, two lines of white-robed figures rising and falling in regular cadence. For perhaps five minutes they dance in one spot; then they pass on a few feet, never ceasing their dancing. The rhythm of the dance is two short notes and one long one [clearly discernible in our recording]. The first two notes the dancers, their hands held in front of them, raise themselves on tip-toe; with the third note they sink on bended knee and raise themselves to their toes again, gradually adding, as the dance continues and the ecstasy increases, a hundred other motions, but never getting away from the rhythm. They may whirl about, they may wave their arms or dance on one foot, but the rhythm, the one-two-three, one-two-three, is always there.

“And after a person has listened to them awhile, he catches himself keeping time to the music, maybe at first only with a fan or walking-stick; then perhaps one finds the muscles of one’s knee stiffening in time to the music, and one may even go so far as to rise on one’s toes and fall back again as the beat, beat, beat of the drums and the wail of the pipes sink deeper into one’s blood.”

The music Holt described is the same captured on this recording at a Friday evening hadra held at the Aissaoua zaouiyya (Taroudannt) during mouloud festivities, coinciding with a moussem devoted to this highly-revered saint, especially favored by the lower classes. Muhammed ben Aissa lived during the reign of the second of the Alaouite rulers of Morocco, the famously ruthless Sultan Moulay Ismail, who ruled Morocco for 55 years, from 1672 to 1727, a testament to his great power and authority to be sure! Moulay Ismail is also remembered for his building, conquests, and control over the disparate and rebellious tribes of the country, not least of which included the Chleuhs of Taroudannt, who attempted his overthrow. They were defeated in 1687, suffering mass executions at the hands of the sultan’s formidable army of black Africans.

Moulay Ismail made Meknes his imperial capital, where Muhammed ben Aissa and his followers resided. These great personalities are connected in story and song, based on an historical association between the two. In this context, it must be remembered that the sultan (now the king) of Morocco is the halifatu lillahi fi ardih (the vicegerent of God on His earth). In addition, the Alaouites, who continue to rule Morocco, presented themselves as shereefs, descendants of the Prophet, and therefore possessors of considerable baraka over and above that of the sultan.

As Ben Aissa had traveled widely in Morocco, there are many zaouiyyas devoted to him throughout the country. His followers are best known for their masochistic derring-do, which may include eating glass, handling red-hot metal with impunity, and devouring freshly slaughtered goats: (after all fall upon the victim and rend the body cavity open with their teeth) “…nothing can stop these madmen who bring each other to greater states of excitement, their beards bloodied, ripping apart with their teeth this meat soiled with excrement. Skin, liver, heart, lungs, trachea, intestines, all is devoured in the wink of an eye: it is the most horrible quarry one could possibly imagine.” [Edmond Doutte: Magie et Religion dans L’Afrique du Nord]. The Moroccan government has suppressed many of their more impressive practices, at least in public. Yet to this day, for example, it is advised to avoid the wearing of black clothing in their presence, as this is taken to be a manifestation of possession by djnun: those so attired are rendered liable to fierce attack at the hands of a devotee. As is customary, the chief musician and singer is the muqaddem of the zaouiyya. In our recording he performs an introductory poem glorifying Moulay Ismail, and asks a “Noble Presence” (perhaps that of Moulay Ismail himself)) to allow the participants of the hadra to embark on the spiritual journey they are about to begin. By affirming “this is neither to sell nor to buy,” any mundanity is effectively removed from the experience.

Our hadra was described by Hussein as a Hadari hadra, “the mother of all hadras.” The instruments used include one large and two smaller flat drums, and two double-reed ghaitas, most often playing the rhythmically-complex melodies in close unison. The melodic scale, as in most Moroccan music, is of limited range with most of the melodies based on 4 or 5 different notes. Adjoining tones beyond this range serve as occasional ornaments. The players employ circular-breathing to play uninterrupted long melodic lines. The oscillating tone of the ghaitas results from the players’ continuous waving of the instruments back and forth. Dancing and trancing are integral parts of the hadra. Most participants engage in the limping-dance during the music, arranged either in a line or circle while others may become overtaken and move about wildly. The tempo increases with each new melody, until those so overtaken generally complete their activity by collapsing to the ground.(Note how the adhan to the salatul-isha (night prayer) emanates from the nearby Grand Mosque at the hadra’s conclusion: Perhaps the muezzin listened for the nearby drumming to cease before determining that it was safe to begin the adhan.) [track 9]

A note about the recordings: The Guerreras and the Hadra were recorded with a hand-held stereo microphone, allowing free movement through the musicians and capturing the performances from a variety of vantage points. Sometimes particular instruments or voices were targeted, allowing the listener to hear the role they played. As a result, the sound is not static, the balance of elements shifting with the motion of the microphone. The performances were not the result of prearranged sessions. All were “encounters,” recorded at public events held during the course of daily life in Morocco. Particularly in the large Guerrera, we find ourselves joining the throng of participants, surrounded by their expressions of enthusiasm and excitement, along with their casual socializing.

— James Irsay ©2000.