Track List

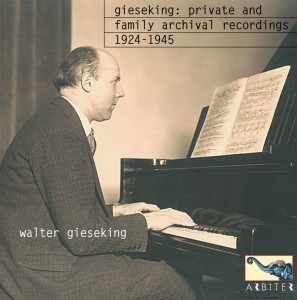

Gieseking's family preserved his archive of letters, photos, programs, and recordings. The performances heard here were located in his own record collection, accompanied by a chronology compiled by his daughter Jutta Hajmassy and a tribute from son-in-law Imre Hajmassy, along with a witty letter penned by the pianist to his wife while on tour in America.

- Schubert Piano Sonata in D. 850: Rondo

- Schubert Piano Sonata in A, op. 120: I

- Schubert Piano Sonata in A, op. 120: II

- Schubert Piano Sonata in A, op. 120: III

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: I

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: II

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: III

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: IV

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: V

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: VI

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: VII

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: VIII

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: IX

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: X

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: XI

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: XII

- Schumann Etudes symphoniques: finale

- Scarlatti Sonata in D minor, L. 414

- Scarlatti Sonata in E minor, L. 23

- Bach WTC Book I Prelude in C sharp

- Bach WTC Book I Fugue in C sharp

- Mozart Piano Sonata in D, K.576: I

- Mozart Piano Sonata in D, K.576: II

- Mozart Piano Sonata in D, K.576: III

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Von fremden ländern und Menschen

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Curiose geschichten

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Hasche mann

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Bittendes kind

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Glückes genug

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Wichtige begebenheit

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Träumerei

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Am camin

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Ritter von steckenpferd

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Fast zu ernst

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Furchtenmachen

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Kind in einschlummern

- Schumann Kinderszenen: Der Dichter spricht

- bonus download track: Strauss-Gieseking Ständchen (1924 unissued disc)

- bonus download track: Strauss-Gieseking: Freundliche vision (unpublished 1924 recording)

A Chronology of Walter Gieseking’s life, prepared by his daughter Jutta Gieseking Hajmassy, in 1994.

1895: Walter Wilhelm Gieseking, born November 5 in Lyon, France. His father, Karl Dietrich Wilhelm Gieseking, medical doctor and entomologist; his mother, Martha Auguste Emilie, nee Bethke.

1902: The family moves to Menton.

1903: First attempts at composition. They move to Villefranche-sur-Mer. No formal schooling: mainly dedicated to butterfly collecting with his father. Unsuccessful violin lessons with Eugène Gandolfo.

1911: The family moves to Germany, staying with Gieseking’s grandfather in Lahde (Minden/Wesphalia). Studies begin at the Hannover Conservatory with its director, Karl Leimer, and playing violin and viola in the orchestra. [Gieseking later wrote a book on piano technique with Leimer.] 1912: First appearance in a school concert (February 7), with other performances on September 4, in October, and on November 25: very favorable reviews from the Hannoverschen Zeitung.

1913: Moves with his mother to Hannover. Conservatory recitals on February 3 (Chopin), April 28 (Schumann), two Beethoven recitals in September. First solo recital on October 24 in Minden: receives fee of 144 gold Marks! A solo recital by Eugen d’ Albert leaves an unforgettable impression.

1914: First Debussy recital in Hannover.

1915-1916 (November-February): Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas in six evenings.

1916: The “music-devotee” W.G. is drafted into the military on August 11. Peculiar decision is made to assign him to serve as a stretcher bearer and military musician, playing in Hannover pubs.

1917: Transferred to North Sea island of Borkum – plays in cafes and for silent films.

1918: Returns to Hannover on December 1st. Piano teacher in the home of Hermann Bahlsen, biscuit manufacturer, who provides generous support.

1919: Many concerts, mostly as accompanist. Performs modern music: Debussy, Ravel, Cyril Scott, Korngold, Busoni, Walter Niemann, Schönberg, Joseph Marx.

1920: Concert manager Arthur Bernstein arranges for a Berlin concert (Singakademie) on October 23. Outstanding reviews in Deutsche Zeitung and Vossichen Zeitung.

Concerts in the Philharmonie:

1921: First performances of Joseph Rosenstock’s Symphonic Piano Concerto on April 8th with the Dresden Staatsoper under Fritz Busch and German premiere of Joseph Marx’s Romantic Piano Concerto (June, Hannover). First concert abroad, in Zürich, arranged by Pianohaus Jecklin (September 21): Scott, Debussy, Scriabin. Two performances of Beethoven’s G major Concerto (Dresden Staatsoper under Fritz Busch). 137 concerts given in 1921.

1922: Vienna debut. Takes part in Salzburg Festival’s International Association for New Music. Meets Paul Hindemith, who soon becomes one of his closest friends. Plays in Sweden, Finland and Denmark (October – November). First concert (October 30) with Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under Furtwängler (Marx Concerto).

1923: Italian tour, concerts throughout Switzerland, Scandinavia, Germany. Premiere of Pfitzner’s Concerto with Fritz Busch (March 16). Further concerts in Berlin with Furtwängler; Bruno Walter and the Concertgebouw (The Hague and Amsterdam); Munich and other cities with Pfitzner. Concerts in Spain, England, Poland & Budapest.

1924: First radio broadcast in England.

1925: Marries Annie Haake.

1926: First American tour. Meets Elly Ney, Toscanini, and Titta Ruffo.

1927: Birth of daughter Jutta.

1928: First concerts in Prague and Paris (with Ansermet).

1929: First performance of Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Sonata (dedicated to Gieseking). Contemporary music program in Berlin: Hermann Reutter, Richard Wintzer, Fidelio F. Finke, Toch, Rathaus, Schulhoff. In New York, plays Scott, Niemann, Hindemith, Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Tansman, Schulhoff, Ravel: poor reception by public and critics.

1930: U.S. tour. Gives eleven North American tours from 1926-1939.

1931: Birth of daughter Freya.

1933: North America.

1934: Family moves to Wiesbaden.

1935: Concerts in Mexico. First performance of Max Trapp’s Concerto (Holland).

1936: Liszt’s E-flat Concerto played in Berlin at the Olympics.

1937: Great success in New York with Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Concerto.

1938: Plays Rachmaninoff’s 3rd Concerto for the first time.

1939: Great success in New York with Rachmaninoff’s 3rd Concerto. Beethoven’s 4th concerto at Salzburg (Böhm/Vienna Philharmonic). With the outbreak of World War II, his concert obligations are cancelled. During the War, concerts given in Germany under difficult conditions as well as in allied and neutral countries.

1943/44: Summer master classes in Braunwald, Switzerland. [According to Jutta Hajmassy, the family went together in 1944 and had access to uncensored newspapers: Gieseking was shocked by what he read and asked the family to defect. Mrs. Gieseking insisted they return to Germany to help their parents through the War, whatever the outcome may be. Her decision prevailed.] 1945: Serious illness at the war’s end (Wiesbaden). He is banned from performing in public for allegedly having been a member of the Nazi Party, which is later found to be not true. Invited to give house concerts for American officers during his de-Nazification hearings and performs in a trio with Ludwig Hoelscher and Gerhard Taschner at private concerts in Rüdesheim.

1947: Nominated to head newly founded master classes in piano at the Saarbrücken Conservatory which draws young pianists from all over the world. First concert abroad, in Paris, acclaimed with extraordinary enthusiasm.

1948: Concert tour in South America.

1949: Teaches seminars on interpretation and Debussy’s complete piano works at the University of Tucuman, Argentina.. A planned concert tour in North America is abruptly cancelled due to misinformed agencies which prevent him from playing.

1951: Highly successful tour in Japan; concert for the royal family.

1952: World tour with his wife and daughter Freya: Australia, Indonesia, Hawaii, Canada, U.S.A., Brazil, Agentina, Chile, Uruguay. Success in the U. S. A., with many concerts.

1953: Recital in Carnegie Hall. Standing ovations. National tour.

1955: Severe bus accident in Stuttgart on December 2 on return from airport. His wife dies and he is badly injured.

1956: Tour in America. September: Luzerne Festival. October 6: celebration of Edwin Fischer’s 70th birthday in the home of Dr. Hans and Susanne Brockhaus, with both masters playing together in joy and harmony. Concerts in Germany, Beethoven recitals in London. October 23: Taken seriously ill, undergoes urgent operation, suddenly dies in London on October 26.

The following memoir was written for this booklet by Imre Hajmassy, Gieseking’s assistant and son-in-law. When I studied in Budapest at the Liszt Academy in the late 1930’s my fellow students and I attended the concerts which took place at the Vigado Hall. Here we heard famous artists such as Sauer, Rosenthal, Rachmaninoff. When Walter Gieseking was announced we knew that he represented the new generation which changed the style of the “Golden Age of Piano Virtuosi”.

None of the grandiose Liszt disciples ever played Bach in concert in the original, unarranged, or any Partitas or Suites. Hardly anybody presented Debussy or Ravel or Scriabin in their programs as Gieseking did. He altered the shape and character of a piano recital in a revolutionary fashion. I only knew his playing from records and radio, so to experience him on stage was an overwhelming experience for me. Once during his encores I stood in close proximity to the concert grand and watched his hands spellbound; their reach easily encompassed a tenth. The sensitivity with which he touched the keys and the sound he drew forth from the instrument were fascinating. During the Second World War I left Budapest for Salzburg to study for two years with Elly Ney. As Gieseking’s playing style had always been my ideal I decided to become his student. In 1945 I arrived in Wiesbaden, played for him, and was accepted as a pupil. This meant a decisive change in both the human sphere as well as musically.

Gieseking’s intention was to communicate to the student the need to learn a composition by heart with utmost accuracy. Subsequently the fingers had to execute what was in the notes: Easier said than done if one has such a head and fingers to follow these commands! He had both. This ability, and his phenomenal photographic memory, are very special divine gifts which are only attainable in a limited way. One has them or doesn’t! Gieseking was also a very extremely patient teacher who let his students know which mistakes were made, what he disliked in their performances, but never “tore their heads off”. If one had to hear the phrase “That doesn’t sound”, one could be sure this meant a sharp and decisive reprimand. It was essential to realize the intention of the composer to the utmost, what could be defined with the word Werktreue (faithful to the work).

Aside from the lessons I was soon a frequent guest in Gieseking’s house and was embraced warmly by the family. Countless images are before my eyes after such a long time but which would exceed the framework of this reminiscence. Just to mention a few instances: Sometimes Mrs. Gieseking, who was highly musical, was present during my lessons. After the eldest daughter Jutta had become my fiancée I dedicated my own arrangements of Hungarian folksongs to her and had to play them for my in-laws, which caused me almost to sink into the ground from embarrassment. Also my corporeal well-being was taken care of: hungry and haggard as I was, the Giesekings shared with me the care packages which they received from caring fans in the U.S. [Food was rationed and scarce in the two years following Germany’s defeat. The family was undernourished and frequently ill as a result.]

Because of the tragic deaths of my in-laws, who were torn away from us in the span of one year, we could only enjoy a few years together, which I remember with gratitude. It is very hard to express in words what Gieseking has meant for my life. The genius, the exceptionally human and artistic personality, the loving family father will always remain unforgettable.

-Imre Hajmassy. Wiesbaden, July 21, 1996.

Jutta Gieseking-Hajmassy has kindly made available a letter written by her recently-married father, then 30, from New York, during his first American tour (winter of 1926). Their family was close and missed him during absences: his letters were eagerly awaited and delighted them with their candor, humor, and observations of life and the musical world.

New York, February 4, 1926

Dear exemplary wife (I presume that this is correct),

Tomorrow there will again be mail to Europe (for the first time this week), meaning that this letter has to go, therefore I start, and that means fff: It is miserable, exceptionally miserable, astonishingly unpleasantly miserable, because this nest [hick town] is, as it were, to puke from, unless one doesn’t have enough work like I had during these last days. Or is it only me and the bad weather? Regardless, [Alfredo] Casella and I re-enforced each other daily; the best thing would be to board a boat tomorrow. This consensus of opinion unfortunately leads to much (leads to nothing). The Casellas also stay here till March while the Baldwins frantically look for engagements for him which should reimburse them for the lost orchestral concerts. He will do some radio concerts pretty soon, I believe, which are pretty good in this country. We might also play on two pianos over the radio, there is also a concert with Szigeti, and the one in public is planned for me. But this doesn’t change at all the fact that I find it extremely miserable (like most of the Europeans who are here). It is also very stupid to be engaged listening to concerts as one’s activity for a whole week. Friday evening I practiced Mozart, etc., during lunch the Casellas invited Signorina Toscanini to our favorite pub. In the afternoon I was dozing around and in the evening went to Toscanini’s concert: he conducted incredibly beautifully. Afterwards there was a big gathering of men at Steinway’s; many colleagues there but as we were not introduced, only the people who knew each other talked to each other. Ole Steinway was extremely endearing, despite the competition. [Gieseking was a Baldwin artist.] [Carl] Friedberg was also there: he is always seen at most concerts and is otherwise only involved in giving lessons and doesn’t seem to be enough of a pianist for here. At the end a conductor of a male chorus who had led the choral festival in Hannover threw himself all over me and, because he had consumed a lot of whisky his tongue had become very lazy, which meant he needed a long time to express his excitement, and he always went over everything from the start. Then on Sunday I was invited to lunch at the Damrosches (the Boss [Gieseking’s nickname for Karl Leimer] calls him the “Director of the Conservatory”.) The whole symphony orchestra was there because of his birthday. It was quite gemütlich: Members of the orchestra were quite good pranksters, especially the flutist, the Frenchman [Georges] Barrère, who plays very beautifully. This one also presented at the Steinways a summary of 35 symphonies in 15 minutes, very funny, all the well-known themes mixed together. A Chinese choir was singing during lunch, to whom some players were bellowing out “Crescendo”. I played something by Bach. By the way, Klemperer, who was also there, doesn’t seem to like these musical pranks. He always looks rather sinister and is also terribly nervous. It is reported that he was bawling in such a way at his cleaning woman during a rehearsal that she almost threw a bucket of water at his head. He was so piqued – asking his wife the other day at Zucca’s not to eat any macaroni – that I believe he is a dragon (and if your husband were that way?). Before I went to this lunch I noticed the museum is closed on Sunday morning and therefore stood in the snow. I rescued myself to the Kaplick’s [singer and voice teacher] who do not live far from there. They seemed not to have gotten up yet (at 12:30!). Those are little mishaps!

On Sunday afternoon I read the Stadts-Zeitung (fine activity). Ate in the evening and then went at nine to a harpsichord-flute concert with the aforementioned Barrère – mostly Bach sonatas, which were for the most part very beautiful. There was also a Sonatina for two flutes by Paule [Paul Hindemith] which was fun.

On Monday, before lunch, I worked at Welte [recording player-piano rolls]: Allerseelen by [Richard] Strauss [arr. Reger, Op. 10, no.8] and Du bist die Ruh by Schubert-Liszt, were completed. Then I played a scandalous piece by Rubinstein [Kammenoi-Ostrow] which Welte wanted to include at all costs, supposedly because they sell that piece as much as all my other rolls combined. And for that money, one can play a piece which other people find very beautiful, and Debussy’s Children’s Corner which came out very well, I think. I’ve received again a comfortable check of $750 (a small consolation!).

In the afternoon I went to the Museum [American Museum of Natural History]: many interesting things, but very few butterflies, a big collection of the Entomological Society seems to be there but I don’t know how to find it. For 15 cents I bought a book about the most common butterflies here, with photographs, according to which there are three very beautiful species (three kinds of giant swallowtails – beautiful, big, brown with silver Argynnis – but before April, nothing). Therefore . . . again a reason for grief. In the evening Szigeti and Toscanini played, I had promised the former to come and therefore I went. He also played beautifully the Debussy Sonata. But despite the fact, I should have gone to Toscanini who supposedly conducted quite incredibly. With Szigeti, Murray and some others, we were again at a German pub where they served a good pancake with cranberries.

(Now I just have to go to Welte at noon today and will continue)

I’m back but in the meantime it is 6 p.m. I was at Welte from 11 to 1:30 because there was much to improve regarding the Debussy (Cathedrale, Puck, Minstrels) [piano rolls were heavily edited]. Then I had to go to lunch in an incredible blizzard on foot because I couldn’t get a cab (in this weather) and at 3:00 was Klemperer’s concert: Meistersinger Prelude, Beethoven G major concerto not badly played by Harold Bauer (he’s dragging too much), and Bruckner’s 8th Symphony, which Klemperer beautifully interpreted and which therefore got on my nerves extraordinarily. I still have not quite recovered yet. It is not the right music when one is already depressed and this at a time when not even half the [tour] period is over! [In a letter written after Klemperer’s rehearsal seven days earlier, Gieseking commented, “Above all else, the ‘Moral of the Story’: When one is out of sorts, do not listen to Bruckner!”] I’m really much too crestfallen to write anything at all – but want to continue reporting, nevertheless! But I have absolutely no recollection of what happened on Tuesday, I believe: nothing happened. Before lunch I was probably at home and in the afternoon I was also bored as well. In the evening I took the subway (cheap) to Kaplick’s house. First we ate something, then a pupil of Kaplick’s came (a tenor), Kaplick sang and unfortunately his pupil did too, who has a huge windpipe but not the slightest idea of bar-lines. One couple and an American woman also came (I don’t think it was the tenor’s wife) and the whole gang sat down and played poker! I obviously didn’t participate and therefore had the dubious pleasure to just watch – which I tolerated for some time but then sat down at the piano and retired after 11:30. Such imbecility – to watch poker – I haven’t experienced for a long time! And this really means something here.

Actually I should really write the Boss? Please excuse me somehow, I’m so uncomfortable to write him with “Du”![colloquial form of you] . . .but we will have to do it sometime!

– translated from the German by Heiner Stadler.