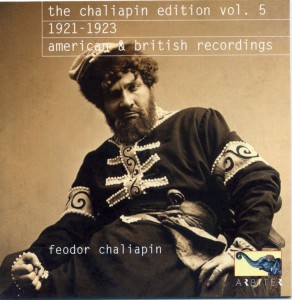

Track List

Arbiter's Fifth volume of Chaliapin's art explores new roles, a recitation of a poem, and contains many rare photos from his vast operatic repertoire.

- Schumann Die beiden Grenadiere

- Koenemann When the King Went Forth To War

- Glinka The Night Review

- Beethoven In questa tomba oscura

- Mussorgsky Trepak

- Mussorgsky Boris Godunov: Varlaam's Song

- Mussorgsky Boris Godunov: Boris' farewell

- Rossini Il barbiere di Siviglia: La calunnia

- Nadson Dreams

- Verdi Don Carlo: Act 4. Dormiro sol

- Koenemann When the King Went Forth To War

- Rimsky-Korsakov Sadko: Varangian Merchant's song

- Folk song: Song of the Volga Boatmen

- Mussorgsky Boris Godunov: Act 1. Pimen's monologue

- Verdi Don Carlo: Act 4. Dormiro sol

- Bellini La sonnambula: Vi ravviso

- Boito Mefistofele: Prologo. Ave Signor

- Folk song: Eh, Vanka

- Borodin Prince Igor, Act 1. Galitzkiy's song

- Mussorgsky Boris Godunov: Act 2. I have attained the highest power

Chaliapin’s first post-war recording sessions in Hayes lasted for four days: from October 9 to October 12, 1921. Two recordings from his third session were included in volume 4. This volume opens with three works from the same day, among them, repeat recordings of The Two Grenadiers by Robert Schumann and When the King went to War by Feodor Koeneman, and the first attempt to record the Mikhail Glinka’s song The Midnight Review. It is interesting to note that Chaliapin’s “obsession” with perfection was so great that of eleven attempts to record the Schumann’s lied, the singer approved only four to be released.

According to Vladimir Gurvich’s final version manuscript of a complete discography, the first two takes of the next session on October 12, 1921 consisted of the Russian Prisoners’ Song (probably The Sun rises and sets): neither were released. Two other songs from this session were first recordings of Beethoven’s In questa tomba oscura and Modest Mussorgsky’s Trepak.

After finishing his recordings and singing five solo recitals, Chaliapin left England for New York. He hadn’t sung in the U.S. since 1908, a time when the majority of the American critics vehemently rejected his art. Thus, his performances were greatly anticipated. Alas, due to a severe cold, he canceled all but one when Sol Hurok insisted that Chaliapin must sing in spite of a throat infection. Only on December 9, 1921 was he able to sing again, in his first appearance as Boris Godunov at the Metropolitan Opera.

“The overwhelming success of Feodor Chaliapin in his two recent appearances in the name part of Boris Godunov [wrote a critic, most likely from ‘The Musical Leader’, as the archival clipping is otherwise unidentified] at the Metropolitan Opera House seems to have put the elder critics of the New York press on the defensive. Perhaps they feel they were not as long-sighted as they should have been when Chaliapin was at the Metropolitan in 1907 and when – so they agree in reminding us – his success was at best only a moderate one. Today, they unite in conceding his genius as an actor, but with here and there a line to indicate an unwillingness to admit, without further proof, that he also is a great singer possessing a superb voice…. It would be interesting to test public opinion today with respect to ‘roughness’, ‘crudities’, ‘gross exaggerations’ and ‘vulgarities’ which were noted in Chaliapin’s Mefistofele, Mephistopheles, Don Basilio and Leporello, in 1907. Have the times changed or has Chaliapin? Or was there, as has been admitted, a variety of myopia prevalent – the result of staring too long and too fondly at the elegantly poised figure of Pol Plançon”.

Suddenly, all the leading music critics in New York were competing with superlative definitions in their descriptions of Chaliapin’s art: colleagues in Boston, Montreal, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Chicago soon followed them. At the end of this visit to the US, Chaliapin made his first American recordings. On January 30, 1922, in the Victor studio he recorded Varlaam’s song and Boris’ farewell from Boris Godunov and also Don Basilio’s aria from Il Barbiere Di Siviglia.

Chaliapin recorded on the following day King Phillip’s aria from Verdi’s Don Carlos and a selection from the poem Dreams by the Russian poet Semyon Nadson (1862-1887). It is well known that Chaliapin was also a prominent narrator and had once considered becoming a dramatic actor. According to many recollections, his ability to recite poetry, particularly of his adored Alexander Pushkin, was unsurpassable. Nadson’s poem is the only known example of Chaliapin reciting poetry. Although, a catalog number (2-021000) was assigned to this recording, it was never published. According to Gurvich’s manuscript, it appeared only on LP: twice in the former Soviet Union by Melodiya and once by the Voce 88 label in Italy, all more than thirty years ago. Our current publication is the first on CD and at the correct speed.

The manner in which Chaliapin recited the poem was quite popular about 100 years ago, and according to his contemporaries, it resembled the manner of the very famous drama actor of those days, Mamont Dalsky (1865-1918). In the beginning of his singing career in St. Petersburg, Chaliapin and Dalsky shared a furnished apartment in a house known as the Palais Royal. Here Chaliapin received from Dalsky his first lessons of acting on the opera stage and years later admitted that in the Palais he studied “Dalchism”.

In March 1922, Chaliapin returned to Moscow with the fixed intention of attaining freedom: “I had become convinced – he wrote in his book – that abroad I should be able to live more peacefully, more independently, without having to put my hand, like a school boy, for permission to leave the room…” But first, he had to obtain permission to leave the country not only for himself but for his family as well. It was not easy, therefore Chaliapin used “the war ruse”: “I decided, I confess, to juggle a little with my conscience. I let it be understood that my concerts in foreign countries benefited and advertised the Soviet Government. Of course, I did not believe a word of this. Obviously, if I sing and act fairly well, it is not due to the Chairman of the Council of the People’s Commissars! God made me thus before the days of the Bolshevism. I merely threw out the suggestion for my own ends.

“However, my hints were taken seriously, and regarded with favour, and soon I had the much-longed-for permit in my pocket, authorizing me to go abroad with my family”.

On June 29, 1922, Chaliapin gave his last free matinee recital in Petrograd and the same evening, boarded the steamboat Oberbürgermeister Hakken to go abroad for “treatment, rest, and guest performances.”

Since that day, although he eventually settled in Paris, Chaliapin wandered around the World for fifteen years, never to return to Russia. The first years were mostly divided between the United States and Europe, as it happened in 1922, when Chaliapin gave recitals in Scandinavia, England, and at the end of October he sailed for New York again.

In England, Chaliapin made new recordings in Hayes over three sessions (September 25th, October 9th and 23rd.) In September, Chaliapin recorded five takes of four pieces: only one – a version of When the King went to war – was released. Five more takes followed on October 9th, with two pieces published. Among them the Varangian Merchant’s song and his first release of the Russian folk song Ei ukhnem, which became internationally popular as Song of the Volga boatmen. Chaliapin apparently tried it for the first time outside of Russia at a concert in the Albert Hall on September 19, 1922. So great was the success of this song that Chaliapin made its first recording the following week but didn’t allow it to be released. The second of three takes made on October 9th became an enormous success and it is heard on this volume. Less fortunate was the following session some two weeks later. After nine takes of five works, only one was approved: Chaliapin’s second and last attempt to record Pimen’s monologue Yet one more tale, from Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov.

Two following sessions took place on November 22nd and 23rd in Camden, New Jersey. On the first day, Chaliapin again took nine takes to record five pieces. Among those commercially released were Rodolfo’s recitative and cavatina from act 1 of La Sonnambula, “Ave Signor!” from Mefistofele, the Russian folk song Eh Van’ka, and Galitsky’s song from act 1 of Prince Igor. Among the first two takes of that session, Chaliapin also recorded King Phillip’s aria from Don Carlos, but none was released. Luckily, the first test record survived in Vladimir Gurvich’s collection and with this CD it is released for the first time.

None of the five takes from a November 23rd session were published and the survival of any test records is still unknown. Volume 5 concludes with a work from the following session in Hayes on June 23, 1923. It presents Chaliapin’s second out of his first two attempts to record a part from his signature role: the monologue “I have attained the highest power” from Boris Godunov. — Joseph Darsky © 2004