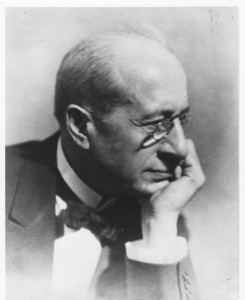

Alexander Siloti’s (1863–1941) first piano lessons were with Nicholas Rubinstein and Zverev, the latter who also taught Siloti’s cousin Rachmaninoff and Scriabin. His harmony and composition teacher Tchaikovsky became a friend and godfather of Siloti’s daughter Oxana.

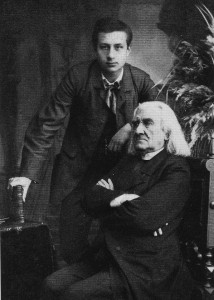

Siloti left an interesting article on his studies with Liszt.

After Liszt’s death in 1886 he returned to Moscow and taught at the Conservatory. He married Vera Tretyakova, daughter of an art lover whose home and collection became the Tretyakov Gallery.

In the New York of 1987 I was told that Siloti had two daughters living near Lincoln Center and that they could not be directly approached, that a proper introduction was necessary in order to contact them. A few efforts by those who claimed they would pass on my request were fruitless impositions on their time. It led me to attempt a call to Kyriena Siloti directly after seeing her listed in the telephone book. She answered drily that there was hardly any time to see anyone as her older sister Oxana was ailing and that she was engaged in her care.

When learning that she had passed, I rang again and Kyriena asked me to come over. Nervously standing outside her door, it was opened by a spritely spirit dwelling within an older exterior.

I was examined by someone appearing to be an Asian scientist in the act of uncovering a new species: her hair tightly pulled back into a severe bun, wearing black-rimmed glasses. She flashed a mischievous Cheshire Cat grin, purring “l’m a peculiar girl!” Once inside, the smiling continued and I sensed a looming Harold and Maude scenario when she mentioned parties that she threw in the apartment to which Stravinsky and Copland often came, and wasn’t it too bad I hadn’t been around to drink with them. She delighted in telling me how as her family sat for dinner with an extra space reserved for Liszt (who died decades earlier), that her brother was engaged in their attic with a chambermaid.

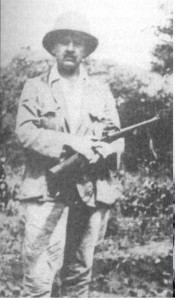

Her English was sharp and well-inflected with a Gallic tinge. Russian came after learning French as her mother-tongue as she had been born in Belgium. The Revolution affected her family and she managed to reach Ekaterinburg, where the Romanovs would be executed. A local butcher was selling meat wrapped in the music editions stamped with her father’s name, raided earlier from their St. Petersburg apartment by the Bolsheviks. A Tibetan lama who had visited the old capital before the Revolution taught Kyriena a series of breathing exercises that she said were beneficial when the temperature dipped as she headed slowly towards Harbin, a heavily Russified enclave for exiled Russians. Kyriena was married to the pianist Boris Lazarev and spent several years there. Another exile on the lam was one Nazaroff, who instructed her with finger gymnastics that he had contrived: she claimed that they provided her hands with the flexibility resulting from two hours’ practice after only twenty concentrated minutes of these Tai-Chi-like gestures. It was most likely Pavel [Paul] Nazaroff, a scientist, spy, archaeologist and botanist among other disciplines,

whose flight from Lenin’s agents is documented in his memoir: Hunted Through Central Asia (Oxford University Press, 2002.) Here is Kyriena’s description of Nazarov’s method:

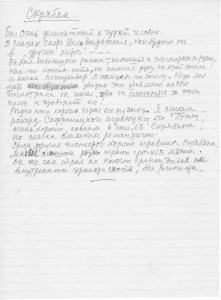

From China she arrived in the United States in 1927 and rejoined her parents and sister in New York. Picking up a volume published in the Soviet Union on his centenary [Aleksandr Il’ich Ziloti: vospominainiia i pis’ma. Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe muzykalʺnoe izdatelʹstvo, 1963], Kyriena pointed out a sentence: “In 1919, he emigrated to America.” Raising her eyebrows, she said in an indignant voice “That’s all they mention. There is much more to tell.” Knowing how she despised tape recorders and interviewers, I asked her what had really happened and after she narrated the account given to her, I begged her to write it out in Russian, as I was soon heading over and would privately circulate it once there. The following pages are in a steady hand, written during her ninety-second year with pre-Revolutionary orthography, such as the ‘yat’ vowel that was removed after the Communists took charge.

Records

In the beginning of the [20th] century during his tour in Europe, Father became interested in a new invention. Out of curiosity he agreed to play on such – a player piano, not anticipating that half a century [later] these pieces would be used for public performance on the radio! I’ve heard that program and was terrified because there was no trace of his individual playing. All his life he refused to make recordings, saying “I cannot play for a machine!” I’m glad that I have a tiny record made by myself at home (when in the 40’s I bought such an apparatus for my pedagogical work.)

[Kyriena had an unheated cabin in upstate New York where she enticed raccoons into the kitchen, feeding them by hand. The record may have been destroyed during a storm but excerpts of Siloti’s playing were recorded by a pupil around 1939-40: two excerpts follow with fragments of Liszt’s 12th Hungarian Rhapsody & Sospiro:]

Father said a few words and then played a few measures from different compositions (even from songs.) This record gives an impression of his individual playing a little.

I’m ninety-two years old, like a lyn’ [bald kite] – wrinkles on forehead as Pushkin said about an old man, but I feel young.

At first, Father did not consider himself a good teacher but after many years, one day he came home from Juilliard and said “It seems to me that I’m starting to know how to teach.” He was very severe with himself.

[The late writer and pianist Sam Morgenstern was a Siloti pupil and had been Joseph Raieff’s roommate when they were students at Juilliard. Raieff came back quite upset after a lesson. Siloti demanded that he only play the bass and melody in the first theme of Saint-Saëns’ Second Concerto as it needed more phrasing. Raieff refused to remove the inner parts and at his next lesson, played the passage as written. Siloti fumed: “Why didn’t you play the bass and melody like I asked?” Raieff replied: “But Mr. Siloti, I have to play the whole piece for the public!” Siloti raged: “The publik! The publik! To Hell mit die Publik!” and threw Raieff out. Raieff tried other teachers and became close to Josef and Rosina Lhevinne.]

With Rachmaninoff we were so close, open, and sincere. Next morning after his concert I came to have coffee with him. Smiling, he asked “How did we play yesterday?” “Wonderful, except for Beethoven.” “What was with Beethoven?” “For me it was not in style.” “Ach! That’s what we think!” and he did not get offended or express his displeasure but only smiled. [Kyriena pointed out that when Rachmaninoff had to reinvent himself as a concert pianist when he moved to the United States, his playing became more exaggerated (example: opening of his Second Piano Concerto recorded in 1929 by the composer. Considered a dim recording, we discovered an Electrola German pressing that better captures Rachmaninoff’s sound:)

and that they preferred his earlier, more direct approach. Here is a recording made by Rachmaninoff for Edison on an upright piano in 1919, his first session, playing his own Polka de V.R.]

On the piano, [Father] practiced fewer hours than most pianists and never worked for more than half an hour at a time, saying that after half an hour, he’s tired. When I told him that I don’t feel tired after a half hour, he said “You don’t work – you play. . .” In 1903 he founded his Siloti Concerts in which he played [as pianist and conductor] classic works [Petersburg premiere of Bach’s Brandenburg concertos] and introduced modern music [Scriabin, Ravel, and Stravinsky, who was first heard there by Diaghilev.]

How Father Left Russia

In 1919, Father left. He had been arrested for ‘disobedience.’ Mother stirred up her friend Dr. Ivan Ivanovich Manukhin (who knew and treated Lenin.) Because of this Manukhin, Father was released from prison and placed under house arrest in the home of Dr. M. Soon they released him but evicted him from his apartment and gave him small quarters, seized his property, piano, music, letters, etc. So father had to go to the Conservatory to practice.

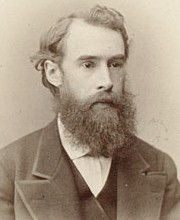

One morning when he arrived, the kind concierge Ivan told him that someone was expecting him and wanted to speak with him. Father unwillingly went together with this stranger to the classroom and as soon as they entered, he quickly turned around and locked the door. Father, ‘taken aback’: “What will happen? Will he shoot me? Will he beat me?” Instead, the stranger removed his false beard and Father recognized Paul Dukes, a young English pianist (my colleague in the Conservatory) whom Albert Coates [conductor and Siloti pupil] brought to our house because we children all spoke English. It turned out that Paul Dukes, while a student at the Conservatory, was training as a future spy for his government. He offered to help with Father and the family to get out of the country. This way, my parents and one sister (who lived in New York until she was ninety-four) were helped with Father’s affairs.

They left Russia in the winter, on the snow in a sled with a white horse, coachman in white overcoat, with white blankets over the Gulf of Finland, passing Kronstadt on the ice, passing into Finland. In Finland the police asked who knows him. He called Erkki Melartin [composer] in Helsinki (the conservatory’s director who came to St. Petersburg for a performance of his music in a concert of Father’s). Melartin said he would send Father some money.

He was famous for his beautiful singing tone.

–Kyriena Siloti, 1987. Translated by Elena Shemetoff

In 1987 I brought copies of Kyriena’s text to Moscow and she was eager to leave one with Sviatoslav Richter, whom Kyriena had befriended when the pianist first arrived in the United States. Not happening to have his phone number and Moscow’s telephone book existing in few unknown hands, my hosts at the United States Embassy pulled out a rolodex and immediately obliged. They were still reeling from the demands of Vladimir Horowitz’s recent return, having to get mylar and cover his windows to block out any daylight, flying in fresh sole each day from Finland for his meals, and to care for all his other requests. They were engaged in arranging a tour for Billy Joel, a much simpler task, especially as perestroika had set in and made it easier citizens to receive foreigners in their homes without retribution. Richter’s secretary greeted me in his top floor apartment on Bolshaya Bronnaya Street, pointing out that the adjacent apartment was lived in by Nina Dorliac, his companion of many decades. Both had a door connecting their kitchens. Richter had massive amounts of video-tapes piled up on a kitchen counter aside a Japanese player and TV set. He was absent for the time being, currently in Germany. His spacious living room was sufficient for rehearsing a modest-size chamber orchestra and she pointed to a book of Italian renaissance paintings: “He starts his day by opening onto a new page and looks at it throughout the day.” Some of his artwork was on the walls, a relief from its Spartan utilitarian ambience. As it was difficult to eat in empty restaurants without a reservation, she invited me to dine at a nearby private Film-makers’ restaurant. Over wine and her seductive glances, she spoke about Richter’s recent tour in Japan that ended in Siberia. Opting to return home by train, Richter’s piano was loaded onto a private railway car that stopped every day at a station along the route. He would have the piano brought to any type of hall or space and offer a recital, doing so for several weeks until arriving in Moscow. She had accompanied him throughout and described how in many villages, the residents had never experienced or heard classical music, nor had every attended any type of recital: “Afterwards there was complete silence, and to show their reaction, these new listeners then stood and start to scream.” While Richter was against a regime that murdered his father, his palatial Moscow residence impressed as a golden cage.

Kyriena on Scriabin

Scriabin was a very delicate and sensitive person.

His eyes often bore an expression as if he was “in a different world” as it were…

He was of modest height, with small and elegantly shaped hands. Once after having sung something, he put his hand at the edge of a table and started tapping against it with his fifth finger. When my mother, having noticed this, looked at him curiously, he said that the pinky concerns him and he is testing it.

It was hard to find good performers of his music. I have heard a recording of a ‘poem’ by Sofronitsky, who performed it very well, in a true Scriabin style, but with a slightly added romanticism.

Among other pianists who play Scriabin well, too many treat the loud sections with too harsh a tone. He himself performed them certainly in a loud fashion, providing the inner drama, without harshness…

translated by Dmitry Rachmanov

–Allan Evans ©2015

Charles Barber wrote a stunning, thorough biography of Siloti. One hopes it will return to print or be accessible in a library or digitally: Lost in the Stars