Everything eventually crosses your path. Last week two momentous events took place, restoring a raw nature of change and transformation that shakes up life’s complacency, movingly depicted in Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali.

The first stirrings in a chain of events began over thirty years ago, stirred up by a recording of Wanda Landowska playing Bach (1685-1750). This composer is so often understood and played as an entity spouting masterpieces in a cohesive style of endless imaginative explorations. But this Toccata in D major breathed its life as a young composer’s creation, sounding as if it still needed to ripen, unlike his later works that impress as received rather than assembled.

Bach Toccata in D, recorded by Landowska in London, 1936.

Each of the Toccata’s several parts vividly flit with distinct rhythms and phrasing, a melange that somehow falls into place. The young Bach copied music for his own use, to be close with its art and his. One composer he doted on was Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643),

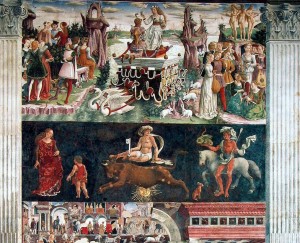

active a century earlier. Bach owned a copy of his Fiori Musicali for organ, not easily found in Germany in the early 1700’s. Listening to Frescobaldi came as a shock, for it exposed an avant-garde composer who was active in the Renaissance’s move towards the Baroque. In his native Ferrara, the ruling Este family had their Palazzo Schifanoia (“palace for ridding oneself of boredom”) with a chamber of frescoes depicting zodiacal and alchemic symbols:

The Este family could have invited the young townsman into this space to relieve their tedium. We are not certain of their contact, but this fresco’s spirit and adventurous nature guided his musical creation.

Frescobaldi moved to Rome and was appointed organist at the nearly complete San Pietro church. At that time, its plan and details were carried out by Bernini and his rival architect Borromini. The Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona has a figure that Bernini shaped with an outstretched mocking gesture of defiance in order to block the horrid view of a church designed by Borromini: in their action dwells Frescobaldi’s art, as they were contemporaries who might have known one another in passing.

Michelangelo disdained Flemish painting:

this art is without power and without distinction; it aims at rendering minutely many things at the same time, of which a single one would have sufficed to call forth a man’s whole application.

Michelangelo introduced the spark of life as a way of burying the Middle Ages’ depersonalized rigidity, and in Frescobaldi this spirit surfaces in sound, a rarity in his time, one leading to Bach and the tradition that followed.

Curious about his presence in Bach’s growth, I began listening and playing his works, finding them enticing in their erratic, odd fragmented confusion and surprising rapid-fire salvos. Frescobaldi left instructions on how to play his music. The composer grants you liberty to stop early if needed, even before finishing a work, to impose or shape any mood, tempo, or expression according to your will and good taste. And yet one heard him played smoothly, sounding straight-jacketed. . . until a recording appeared by Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini. The Fifth toccata with and without pedal is played on a 17th century organ at the church of San Bernardino di Carpi in Modena, Italy:

Frescobaldi Toccata V sopra i pedali e senza

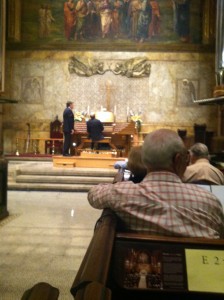

Frescobaldi’s harpsichord works also incorporated popular and folk melodies into dance rhythms, an example noted by Bach. It was a revelation to hear Tagliavini play a recital in Civitanova Alta (Macerata), Italy some twenty-two years ago and last week he returned here to New York after an absence of twenty-five years. His program focused on Frescobaldi and its influence on Bach and beyond, at the Church of the Ascension on it’s newly built organ, freshly in place after arriving from France.

The accuracy of Tagliavini’s playing and conception proved exemplary in illuminating and bringing to life older practices, restoring an audacity and freshness. He is one of the few to have made sense of Frescobaldi and a path leading to Bach. I had to thank him and ask if he would explain the steps and approaches he took in decoding Frescobaldi. He kindly conceded an interview the following Sunday. Tagliavini at once mentioned that discovering the music was aided by playing on antique harpsichords:

interview with Tagliavini, 6 May 2012

. . .yes, in a certain way, because the way modern instruments which we have available at music conservatories aren’t the ideal instruments for Frescobaldi, and instead it was Frescobaldi that I discovered on these old instruments. It’s not only the sound, it’s a laborious way, above all in the works, in the most ingenious works by Frescobaldi, the Toccatas, that are beyond what the music that came after it conditioned us to expect. For example, when we listen to Mozart, not that we know, but we think we might be able to predict how he will continue his discourse, quite often it’s not true because he’s too ingenious as a composer, but what I’d like to say is that the music has this side of predictability, you can predict or imagine. In Frescobaldi, no! you can’t predict it. It’s not a casual improvisation, it’s quite a profound imagination and a structural law which is extremely free.

Tagliavini has extensively examined tablature and manuscripts to further his decoding of touch and ornaments, tempi, all tacit elements embedded within threadbare intimations of notation. For decades he has studied harpsichord construction and amassed a collection of over seventy instruments that have been recently loaned to a museum in Bologna, Italy with the proviso that they are kept in use rather than be displayed in silence:

Research never ends as Taglaivini now prepares his new edition of the Fiori Musicali. His decoding of Frescobaldi by accessing elements from his time based on studies and a remarkable ear and judgment lead the once-unfathomable music into a renewed existence.

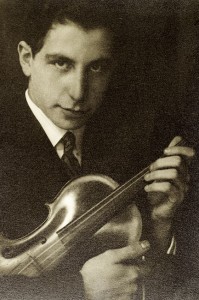

As Sunday’s interview morphed into a conversation, violinists were rushing over to Newton outside of Boston as Roman Totenberg lay on his deathbed. In a diary from 1943, Mieczyslaw Horszowski noted a radio performance of Beethoven’s first violin sonata with Totenberg. Checking his name in 2010, his birth year of 1911 was followed only by a dash.

I located a radio program produced by his daughter Nina Totenberg for his 96th birthday:

On the side was a link to a Totenberg recording of Beethoven’s violin concerto. How did Totenberg play? There were no available recordings at this time. Usually this Beethoven is served up grandiose, overblown, a technical tour-de-force underlined with elemental struggle. Totenberg approached it from a height, an Olympian gaze onto its emotional terrain, inner being, all played in an assured resolute calm, as one sensed how in every phrase and tone he was more involved in listening than merely playing an instrument. Nina Totenberg immediately responded and mentioned that her father was still quite busy, teaching, and would be delighted to get a call. I phoned him at once and we began to examine and explore his art and life for the next two years, publishing a CD edition based on remarkable recordings that had lain in the shadows of his basement for nearly a half century.

A stunning abundance of extraordinary recorded performances appeared on each and every bookshelf, in desk drawers, enough repertoire to cover a good dozen essential CDs. We began to finalize a second project, sonatas with Jorg Demus and Philippe Entremont. When mentioning Roman to these pianists, they sighed and expressed gratitude for the rare experience he provided them, retaining vivid epiphanies decades later. In the basement was a broken disc, partially playable, offering a rare glimpse captured in Warsaw around 1928, in his seventeenth year. Novacek’s Perpetuum mobile was a technically daunting virtuosic display, quite evident here, yet the main focus is on an exquisite tone and energetic heat:

Novacek perpetuum mobile 137003 Odeon 253687b

We have few traces until 1939, when a performance of Mozart’s Violin Concerto no.3 was caught on deteriorating homemade lacquer discs that had peeled, surviving its final playback.

Here is the lead into its first movement’s cadenza, projected with a refined style and warm expression. When playing it for Roman, he didn’t recognize the cadenza, guessing that it was something he improvised on the spot:

One can hear a remarkable development in his art via the third movement of Brahms’s Third Sonata for Violin and Piano on the Arbiter CD, its informal poise masking a remarkable precision that makes this tossed-off movement offer profundity and sound definitive in his hands:

After his one hundredth birthday, Roman tended to repeat favored anecdotes, yet when we once switched to French a new trove opened onto unfamiliar episodes emerging from storage within another language vault.

His art made a profound change in my perception of using the violin for music. Aside from him, Huberman, and Erica Morini, many legends and grand names of past and present seemed limited by their superficiality, ego, tonal fetishism, maudlin asides, good moments followed by dubious voids. Totenberg fitted all into a natural balance, illuminating the music. Of the hundreds of students he shaped into artistic maturity, news of his end reached many. The scene developed during his final hours found dear and devoted students rushed over, one driving for six hours, all with violin in hand, to serenade him in the last moments. Hardly able to speak, he beat time with his foot and arm, even whispering corrections:

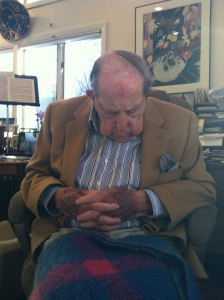

Bronislaw Huberman heard the eighteen-year old Totenberg in 1929 and provided him a scholarship to leave Warsaw for studies in Berlin. On our last meeting I played Roman a performance by Huberman in Brahms’s violin concerto, captured in New York, 1944. He sat in rapt attention throughout, stunned, nearly speechless afterwards.

While Totenberg’s physical passing leaves us a void, his art remains and so much is awaiting recovery from archives throughout the world, and his legacy lives in pupils who are teaching and performing, passing on his knowledge. Its depth grew out of a grand culture, a century of contacts with great artists, guided by the originality he possessed. When asked about his Bach, if Casals or anyone else had influenced it, he replied “No. I spent a few weeks on it in Rome in the 1930’s and worked it all out.” Bach’s Presto in G minor (1971):

Roman: you were a grandpa and guru! And we won’t allow your music or memory to rest in peace.

©Allan Evans 2012

Allan,

As always, you bring together disparate ideas that congeal into a whole — informing us of the vastness of great expression and human experience. Your heartfelt words and wonder illuminate these great artists’ expression — revealing something new — a window into the divine where words fail and we are left with pure utterances of spirit!

As always,

Evan Tublitz