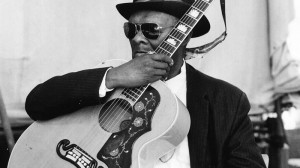

Keep listening to Rev. Davis and you’ll wind up with observing emerging architectonic details with each encounter. Meditate or think about it all and you will be drawn into his thinking on a structural level. For example, in the mere opening of Twelve Gates to the City that he played at the 1967 Newport Folk Festival we find that each and every gesture introduces itself and will be worked out in time, as did Mozart and Haydn with a gambit readied in their opening themes (string quartets, sonatas, symphonies).

His melodic notes pop out in the mid range, a high voice, and some rhythmic action develops in the bass. Beyond notes, every piece he played bears rhythmic identity, actually two: the work’s, and his own.

The luscious A chord arrives after an open E string serves as its diving board.

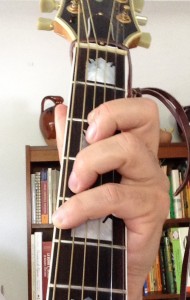

He voices the chord polyphonically to bring two registers in with a rich baritone ‘C-sharp’ below a higher ‘A’. When I played it with my fingers crushed on the second fret, he corrected my position with this spread he developed to play the chord with a unique voicing. His deliberate tonal balance of an A chord employs a resonant open E (6th string) leading to a a tightened A formed with the pinkie as the gang leader when it follows the E, resulting in a taut chord that he strokes.

Next he swings the A chord and places an open D string before playing a very cool bent C with the open G string leading to more chromatic adventures via a G-sharp to E close, drawing attention to the ‘blue’ note that is bent between C and C-sharp: the modal role of the open D and inflected C shape the piece’s identity. To get that open D, the sprawled A chord’s hand position gets uplifted for a sec into space and lands with the index + middle fingers squatting on the second fret.

Moving to a D chord, he has an open A grace note that not only carries on the presence of the earlier A triad but blends into a new harmony that maintains his rhythm.

With all the implications of higher notes itching to appear, Davis instead has the bass intrude with a lively bounce that resolves with a high-voiced E /E7 chord:

The E7 chord finds the melody continuing in a lower register and again, as the piece began, he punctuates the action with the lowest pitch on the guitar, its open E string that rings as he positions above another unique position at the 4th fret, an F-sharp-diminished -7th chord:

With one motion he invokes the lowest frequency to cushion a flash of the highest pitch so far atop an ornamented diminished chord that rapidly returns to the fundamental A harmony that again, after a reply from the grumbling bass tones, he closes with a syncopated arpeggiation of the tonic chord in the bass to end the intro without making it feel stable as it lacks a full cadence, creating expectation that he will soon start singing :

These are but mere details, child’s play for Rev. Davis, but under our microscope we observe a strategy and nuance guided by his refined taste and style that lead right into the highest spheres.

After hearing these details, try listening again to the unbroken intro and notice how you hear it now:

Learning his way of playing has remained a lifelong addiction and act of purification that I just can’t quit!

Allan Evans ©2014

Yes, the Rebbe has mastered Blues syntax, which is left for the likes of us to inspect up close from afar. That second example, the A chord, has a guitar G sound, from its configuration, or “confingeration”. Actually one of the very nicest and freewheeling gestures he makes is in the first example at 00:16 – those high G#-A-G#-E 16th notes followed by LOW triplet Eb-D-C# up to A. What an ear for decorative notes! Only a player who owns his style can do things like that.

In fact, he often alters the “usual” blues mode by not lowering the seventh scale degree, as in the run at 00:16 and elsewhere.

When he does lower the 7th degree – e.g. in example 3, when he plays the tenor G natural – and then closes the riff with the G# just above, he puts our ears in quite an interesting place… very 16th century.