Track List

"Only a genius plays so." –Anton Rubinstein, after hearing Huberman's recital in Berlin, 7 October 1892. Live performance of Beethoven's Violin Concerto from 1944. 1-4 with Leon Barzin and the National Orchestral Association 5-6 with Ignaz Friedman, piano 7-8 with Boris Roubakine, piano In 2014 this CD was remastered for downloading that contains an additional bonus track of the Beethoven sonata's second movement, making it a complete performance.

- announcement

- Beethoven Violin Concerto: I

- Beethoven Violin Concerto: II

- Beethoven Violin Concerto: III

- Beethoven Sonata for Violin and Piano in A, op. 47 "Kreutzer": II

- Beethoven Sonata for Violin and Piano in A, op. 47 "Kreutzer": III

- Smetana From my homeland

- Bach-Huberman Nun komm der Heiden heiland

- bonus download track: Beethoven Sonata for Violin and Piano in A, op. 47: II

“A judgment of Huberman is quickly rendered. He is simply a phenomenon, an apparition before whom criticism ceases. Mind you, Huberman was never that which is known as a ‘child prodigy’. At the age of six years, he was already a miraculous man who, far from being reduced to normal stature, kept himself at an illustrious height.”

–Theodor Leschetizky. Vienna, 25 December, 1898

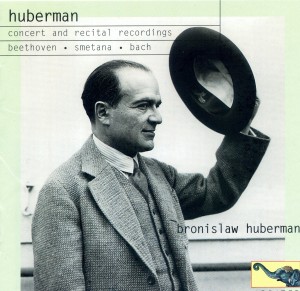

It is surprising to discover a group of concert performances by an artist who died more than fifty years ago, an opportunity unlikely to occur again. Musicians such as Bronislaw Huberman (1882-1947) did not respond well to the sterility, acoustics, and limitations of the recording studio. When Huberman made discs of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, he was obliged to break the continuity every four minutes and discuss whether to play the same excerpt again or go onward. The record company’s choice of such a draconian and inhibiting conductor as George Szell did not help matters either. Although the disc’s excellence is a tribute to his professionalism, was there more to Huberman’s Beethoven? The recent discovery of a 1944 War Bond concert of Huberman with Leon Barzin and the National Orchestral Association reveals how a public performance allowed his artistry to fully emerge in a work of great significance.

In addition, the survival of a portion from a recital (possibly from 1942) with his superb pianist Boris Roubakine, contained a work new to Huberman’s recorded repertoire: Smetana’s From My Homeland, which appeared in Huberman’s programs in the 1940’s. When he became the first soloist to appear in Milan’s Societ· del Quartetto concert series after the Second World War, the Smetana was included in his recital. It is an important example and illustration of Huberman’s life-long affinity with Central European music and culture, as his playing style found its most fervent listeners in Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, Hungary, Austria, and Germany. On the same program, he offered his own transcription of Bach’s chorale Nun Komm der Heiden Heiland. Although Huberman recorded the Bach more than once, his tempo was rushed to meet the disc’s limited time capacity: the recital recording instead bears an expansive tempo, his true approach to the work. Although the final bars are missing due to the acetate’s limited playing time, its musical importance makes publication imperative.

Huberman’s collaboration with Ignaz Friedman in Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata is well known, yet the 78 rpm sets released in England and America contained different takes. We include here the first and third movements from the American edition, as the only available recordings are from the British version. The second movement is identical in both albums, thus their alternate performances are published here a supplement to the complete recording, which has been published by other companies.

Huberman is now viewed as a mythic figure from a golden age of violin playing. His playing of the Brahms concerto moved the composer to tears and brought forth a promise to create a concert work for the young artist, which was prevented by Brahms’ declining health. He collaborated with the finest musicians of his time, such as D’Albert, Friedman, Casals, Furtwängler, and Bruno Walter. Going beyond the province of a master musician, Huberman’s tireless efforts to oppose Fascism and saving an entire orchestra from the Nazis by creating the Palestine Symphony bespeak the heroism of a world figure. During his lifetime, Huberman’s art was contested and defended. His colleague Carl Flesch took a harsh view of Huberman, based primarily on the early phases of Huberman’s playing. The following are excerpts from Flesch’s Memoirs, and a response by Hans Keller. Flesch writes of his years in Bucharest, Romania from 1897-1902:

“It was in Bucharest, too, that I first met and heard Bronislaw Huberman. about whose stature there is sharp disagreement. While most of the violinists of his generation have adopted a negative attitude towards him, he is highly esteemed by a number of his younger colleagues as well as by the general public. If one wants to understand his style, one has to bear in mind above all that he is basically self-trained, for he only took lessons until he was ten, and irregular ones at that. Originally a pupil of Michalowicz and also, occasionally, of Marsick and Joachim [he studied with Joachim for eight months in Berlin in 1892], he soon followed his own intuition, sharply defined as his personality was at an early stage. After his sensational success at Adelina Patti’s farewell concert in Vienna on January 12, 1895, he entered a period of triumphs which lasted, approximately, until the age of puberty. His development then seems to have gone through a crisis which was only resolved after a decade, to give way to a renewed ascent. Ever since, he has been playing uninterruptedly all over the world.

“Two factors are decisive if we wish to judge a violinist objectively: his technical grounding and his particular personality. Huberman’s technique, though sound, has always betrayed the fact that he left school too early. His technical basis is that of the 1890’s. He holds the bow in the old manner, employs a pure finger vibrato without participation of the wrist, and intones semitones pianoforte-like, according to equal temperament – a circumstance which becomes particularly and unpleasantly striking in his unaccompanied Bach. In tonal respects, too, he follows the tradition of his childhood in as much as he sacrifices smoothness and evenness of tone production, which in our time is an absolute necessity, to extravagant characterization; in other words, he either ‘scrapes’ or ‘whispers’. His bowings again, excellent as they may be in themselves, leave much to be desired from the tonal point of view. Unreserved praise, on the other hand, is due to his runs and passage work, the precision and verve of which meet the most fastidious requirements.

“Musically, too, his style gives occasion for serious criticism. The fact that he was left to his own devices at an all too early stage shows in his frequent neglect of elementary rules of articulation, especially in the form of wrong accents. Above all, however, it is the over-emphasis he lays upon his own personality as distinct from the work of art, that characterizes both his good and his bad performances. His personality is self-willed, sensitive, nervous and excitable, passionate and self-assured. It does not tolerate contradiction and demands subordination, even of the music. In this way, extraordinary results can be achieved if composition and interpreter are in natural harmony with each other, whereas otherwise Huberman always tries to adjust the tone of the work to the pitch of his own ego. Agreement or disagreement with his interpretations depends chiefly on the degree of sympathy or antipathy which the individual listener feels for a personality so full of contradictions. Side by side with his serious artistic intentions, his extreme drive for perfection, his acute intelligence and his iron will, there is this, at times, downright amusing over-estimation of his own self – which, in favorable circumstances, may yet again result in an extraordinary power of artistic conviction, to whose hypnotic suggestion the receptive listener submits unresisting. The strength of his personality, then, is undeniable, like it or not. Its influence on the younger generation, however, would seem to be unfavorable; young people tend towards self-glorification at the expense of the music, and Huberman’s successes are likely to confirm them in their attitudes.

“Huberman cannot be placed in any school or line of development. In the history of violin-playing he will survive as the most remarkable representative of unbridled individualism, a fascinating outsider.”

The following appendix by Hans Keller in Flesch’s book offers a differing opinion:

“Flesch and Huberman were opposite musical characters, and Huberman is the one figure in this narrative towards whom Flesch is unable to maintain his uniquely objective attitude, shown, for instance, in his characterizations of such opposites as Rosé and Heifetz, or in his description of Joachim’s playing, of which I happen to have some idea from a very old record, and with which, paradoxically enough, Huberman;s style seems to have had much in common.

“It seems moreover likely to me that Flesch had last heard Huberman long before I heard him first, for not even his purely technical observations apply to the Huberman I knew: since Huberman’s was a strongly developing personality, Flesch and I may at times be talking, as it were, about different artists. At the risk of momentarily extending my editorial function, then, I feel that I might profitably offer a rejoinder and some complementary comment to Flesch’s observations.

“Huberman was one of the greatest musicians I have ever come across. Right or wrong, mine is not altogether an eccentric impression: a long line of artists has testified to his towering stature as an artist, violinist and man, including such vastly different musical character types as Brahms, Toscanini, Bruno Walter and Furtwängler.

“In general, Huberman’s technique seems to have undergone various changes in the course of his development. It certainly was always individual, and to some extent it depended on his mood, and his on- and off-days. When he was ‘on form’, both hands evinced a virtuoso technique of the utmost brilliance and an almost uncanny verve.

“More in particular, when I heard him, he did no longer hold the bow ‘in the old manner’, nor did he ‘whisper’ at a low dynamic level. Typical of his ever-changing interpretations was a tendency towards the sharpest possible characterization and, consequently, an occasional extreme pianissimo of the greatest intensity. I have never again heard the entry of the second subject after the cadenza in the first movement of the Beethoven Concerto played so softly and intensely, yet restrainedly and without incidental noises (Unluckily, I never heard a Flesch concert.) [Note: a concert performance of the Beethoven played by Flesch was published on cd by Symposium.]

“He no longer used a ‘pure finger vibrato’ when I heard him, nor indeed was his finger vibrato like other people’s. It was determined, on the one hand, by his very original sound-ideals, and on the other hand, by the peculiarities of his left hand which, so far as ‘trembling’ movements were concerned, seemed to function in a highly individual manner. For instance, he would execute the fastest and clearest possible shake with a stiff and stretched fourth finger, by way of a vibrato-like motion. His records show that his vibrato, far from being inadequate, was capable of the subtlest differentiations.

“In view of his records, the reader will be puzzled by Flesch’s remarks on Huberman’s intonation. It was the very opposite of a ‘well-tempered’ intonation; in fact, I do not know of another violinist who adjusted his intonation so consistently to harmonic and melodic requirements.

“Naturally, with a violinist whose technique can be erratic, critical appraisal will easily be one-sided if his development is not closely followed. While Flesch prefers Huberman’s left hand to his right, Grove IV speaks of his ‘excellent technique, especially of the right hand’: evidently, it all depended on when you heard him. Nor did I find any ‘neglect of elementary rules of articulation’, and as for the ‘overemphasis Huberman lays upon his own personality’, a powerful personality we do not take to will always seem to us egocentric. Huberman’s musical character had affinities with that of Furtwängler, one of his profoundest admirers, whose own intense personality likewise aroused the impression of self-centredness amongst those who reacted against it.

“As a man, finally, Huberman showed his passionate intellect and integrity for a United States of Europe, in his famous ‘J’ accuse’ (1933) in reply to Furtwängler’s invitation to play in Germany after the Nazis had assumed power and, most important, in his founding, in 1936, (after about a year’s strenuous efforts entailing innumerable auditions), what has meanwhile become the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra- an achievement which Toscanini helped bring to fruition.

Allan Evans © 1998.