Disc 1

1-3 Erica Morini, violin; Georg Szell & the NYPSO, rec. 25 XII 1955 first release 4-6 Konstantin Igumnov, piano, rec. 1947 7-9 Alfred Hoehn, piano; Wilhelm Buschkoetter & Stuttgart RSO rec. 30 VI 1937 first release 10 Sergei Rachmaninoff, piano, rec. 3 V 1920

- Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto Op. 35: I. Allegro moderato (with cuts) 16:17

- Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto Op. 35: II. Canzonetta. Andante 5:58

- Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto Op. 35: III. Finale. Allegro vivacissimo (with cuts) 7:50

- Tchaikovsky-Pabst: Kolykol'naya pesna, Op. 18, no.1 3:51

- Tchaikovsky: Aveu passionné 2:41

- Tchaikovsky: Rêverie du soir 3:34

- Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 in Bb minor, Op. 23: I. Andante non troppo e molto maestoso 19:13

- Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 in Bb minor, Op. 23: II. Andante semplice. Allegro vivace assai 7:42

- Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 in Bb minor, Op. 23: III. Allegro con fuoco 6:53

- Tchaikovsky: The Seasons, Op. 37, No. 11. Troika 3:44

Disc 2

1 Issay Dobrowen & the Danish RO, rec. 1950 first release 2-9 Oskar Fried & the Berlin Staatsoper Orchestra, rec. 14 XII 1927 10 Michael Zadora, piano, rec. 1929 11 Vassily Sapellnikoff, piano, rec. 1925 12 Alexander Kaminsky, piano, rec. c. 1950 13 Issay Dobrowen & the Berlin Staatsoper Orchestra, rec. 13 IV 1929 14 Albert Coates & the London Symphony Orchestra, rec. 2 IV 1929 15-16 Igor Stravinsky & the NYPSO, rec. 17 I 1937, first release 17-19 Konstantin Igumnov, piano, rec. 1935 20 Vladimir Sofronitsky, piano, rec. 1960 first release

- Glinka: Russlan & Lyudmila Overture 4:35

- Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite. Miniature Overture 4:35

- Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite. March 2:34

- Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite. Dance of the Sugarplum Fairy 1:58

- Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite. Russian Dance (Trepak) 1:05

- Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite. Arabian Dance 3:50

- Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite. Chinese Dance 1:20

- Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite. Dance of the Reed Flutes 2:52

- Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite. Waltz of the Flowers 5:04

- Prokofiev: Prelude Op. 12., No. 1 in C 1:35

- Glinka-Balakirev: The Lark 3:13

- Musorgsky: Pictures from Crimea, No. 1: Gurzuf at Ayu Dag 4:37

- Borodin: Prince Igor: Polovetsian Dances 7:31

- Borodin: From the Steppes of Central Asia 6:57

- RImsky-Korsakov: Sadko Suite 11:29

- Stravinsky: Fireworks (with announcement at end) 3:56

- Chopin: Mazurka Op. 56, No. 1 in B 3:11

- Scriabin: Mazurka Op. 25, No. 7 in F# 3:41

- Scriabin: Poème Op. 32, No. 1 in F# 3:50

- Scriabin: Poème Op. 69, No. 1 1:54

Andrei Bely

Igumnov seduces with Tchaikovsky-Pabst’s Kolykol’naya Pesna (from CD I), played at his final recital months before his death in 1947

There is no doubt that the [religious] Schism separated us from the rest of Europe and that we have not participated in any of the great occurrences which have agitated it. But we have had our own special mission. Russia, in its immense expanse, was what absorbed the Mongol conquest. The Tatars did not dare to cross our western frontiers and leave us to their rear. They withdrew to their deserts, and Christian civilization was saved. For this purpose we were obliged to have a life completely apart, one which though leaving us Christians left us such complete strangers to the Christian world that our martyrdom did not provide any distraction to the energetic development of Catholic Europe.

– Pushkin to Pyotr Chaadayev, 9 X 1836

How does one begin to grasp Mother Russia, how her spell-binding music suddenly materialized, her enigmatic people? Their identity fused European and Asian elements and when Western classical music arrived, it fell onto what the writer Andrei Bely (1880-1934) described as the “two Russias, between which lies an abyss.” Bely first considered studying music until he became spellbound by philosophy and the emerging Symbolist poets and painters. Influenced by Schopenhauer, Bely described music as “quite independent of the phenomenal world… [It is] a copy of the will itself… For this reason the effect of music is so very much more powerful and penetrating than is that of the other arts, for these others speak only of the shadow, but music of the essence.” As an erupting passion for music created divergent paths for those looking westward, some conservatives followed the Germanic traditions imported by Anton and Nikolai Rubinstein, while independent seekers shunned European models to create music that drew inspiration from their myths, fairy tales, as well as Central Asian influences that led to the Silver Age and its quest for outsider realities. For Bely, music is “so to speak, the equivalent in this life of the next world.”

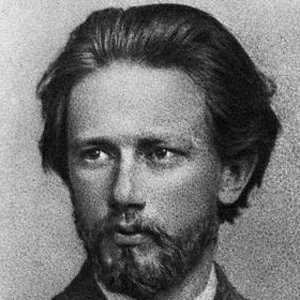

Of his Russianness, Bely writes: “Russia is a Mongol country. We all have Mongolian blood in our veins and [therefore our nation] will not resist the invasion. We are fated to prostrate ourselves before the idol.” Tchaikovsky’s contact with folk music came during holidays in the Ukraine and his gift for composing in dance forms led to the development of Russia’s phenomenal ballet tradition. In 1878 he wrote to his patron Nadezha von Meck (1831-1894): “Perhaps the Russian character is at fault, not without reason, for a lack of original creativity precisely because the Russian is lazy par excellence. The Russian likes to put things off. He is talented by nature, but it is by nature, too, that he suffers from a lack of will-power and endurance.”

An early catalyst in Russia’s search for a musical identity appeared through a fifty-one year old Roman, Muzio Clementi (1752-1832),

a recent Londoner who published his own compositions and built pianos. In 1802 he received John Field (1782-1837),

a twenty-year-old Dublin pianist best remembered for creating the Nocturne. Field took lessons and demonstrated Clementi’s instruments. The duo set off for European capitols and set up in Moscow a year later. Clementi soon had enough of Russia and returned to England whereas Field stayed on for nearly three decades, touring abroad from his Moscow base. Among his pupils were two who would lead to an exponential change the shape of the world’s music by enlivening Russia as a provincial backwater into a dominant world force within sixty years.

Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857)

began introducing Russian folk music into operas that were to rival Europe’s. Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

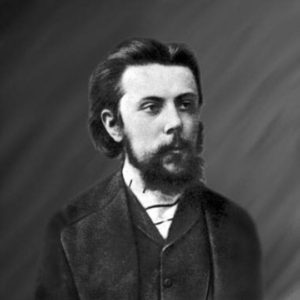

was first inspired by both Mozart’s Don Giovanni and Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar, describing the latter as “the corner-stone of Russian music.” Tchaikovsky’s contemporary Modeste Musorgsky (1839-1881)

went even further, describing Glinka as a creator “who first pointed out the path to truth.” Glinka’s influence remained with Tchaikovsky and Musorgsky as they developed individually.

Tchaikovsky affirms his goals: “So many talents, from which, with the exception of Korsakov, it is difficult to expect anything serious. Isn’t that the case with everything in Russia, though? Huge strength, which some fateful Plevna prevents from stepping out into the open field and fighting as one should. Still, this strength is clearly there. Musorgsky, for all his music’s ugliness, does speak to us in a new language. It may not be beautiful, but it is fresh. And that is why we can hope that Russia will one day produce a whole pleiad of powerful talents, who will open up new paths for art. Our ugliness is at any rate better than the wretched feebleness, camouflaged as serious music, which we find in Brahms and suchlike Germans. They’re played out for good and all…”

During his 1888 European tour Tchaikovsky wrote his younger brother Anatoly: “I’ve met an incredibly large number of people here. Amongst these Brahms and Grieg stand out in particular. Brahms is a pot-bellied boozer, together with whom I got myself pretty drunk yesterday at Brodsky’s house. Grieg is an uncommonly nice man of my age.”

How did Tchaikovsky face a composer who was then the height of German music? From Leipzig he writes to Grand Duke Konstantin:

“With regard to Brahms I do not quite agree with Your Highness. In the music of this master (for his mastery can of course not be denied) there is something dry and cold which repels my heart. He has very little melodic inventiveness; his musical thoughts are never spoken out to their conclusion; no sooner has one heard a suggestion of a melodic form that can be easily appreciated, than the latter has already sunk into a whirlpool of meaningless harmonic progressions and modulations. It’s just as if this composer had deliberately set himself the task of being unintelligible; what he does is precisely to tease and irritate one’s musical feeling.

He does not wish to satisfy the latter’s needs, he is afraid to speak in a language that reaches the heart. His depth isn’t real — [French: ‘it is assumed, artificial’] — he seems to have decided once and for all that it is necessary to be profound, and it is true that he has a semblance of depth, but only a semblance. His profundity is empty. One can’t say that Brahms’s music is feeble and insignificant. His style is always elevated; he never chases after outward effects, he is never banal; everything in him is serious and noble, but the most important thing is missing — beauty. It is impossible not to respect Brahms; one cannot fail to bow before the chaste purity of his aspirations; one cannot but marvel at his steadfastness and proud refusal to make the least concession to triumphant Wagnerism, but it is difficult to like him. In my case at any rate, no matter how much I’ve tried, I simply haven’t been able to. Many Brahmsians (amongst them Bülow) have been telling me that one day I will see the light and begin to appreciate the beauties of his music, which to me are now unattainable, and that is not impossible, since there really have been such cases. Brahms’s Deutsches Requiem I hardly know at all. I shall order a copy of the score and set about studying it. Who knows, perhaps there will indeed be a drastic change in my attitude to Brahms?”

Yet Brahms witnessed Tchaikovsky’s conducting at a dress rehearsal for his First Orchestral Suite, Op. 43: “When we greeted one another afterwards, Brahms did not say a single encouraging remark, but, as I was told later, he had been very pleased with the first movement. The others, however, had not been to his liking, especially the fourth movement (Marche miniature).” A disparity comes in their dances: Tchaikovsky’s rhythms and ingenious melodies instigated movement that influenced the development of the Russian ballet whereas Brahms’s Hungarian Dances impress as background music for habitués in an imaginary café who remain seated as they listen. Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894), a composer and Russia’s leading pianist, offered an extensive recital series of historic repertoire spanning from the Elizabethans to the present, and never included Brahms.

Musorgsky disdained European idioms: “Symphonic development, like German Milchsuppe or Kirschensuppe is a calamity for us but Germans love it. In short, symphonic development, technically understood, is manufactured by a German, like his philosophy. A German, when he thinks, starts by analyzing then demonstrates, while our [Russian] brother starts by demonstrating, and only then amuses himself by analyzing.”

Like a Chekhovian character, Tchaikovsky berates his dislike of them to his unseen patroness: “Musorgsky flaunts his illiteracy, takes pride in his ignorance, and turns out [his works] anyhow, blindly believing in the infallibility of his genius. And yet he does sometimes have flashes of real talent, and, moreover, not without originality… For all his ugliness, Musorgsky does speak to us in a new language. It may not be beautiful, but it is fresh.”

With a new concerto successfully composed in a Western form, Tchaikovsky wrote of its unwelcome reception abroad:

“In 1877, I wrote a Violin Concerto and dedicated it to Mr. L[eopold] Auer.

I do not know whether Mr. Auer felt himself flattered by my dedication, but the point is that, in spite of his genuine friendliness towards me, he never wanted to surmount the difficulties of this concerto and in fact pronounced it to be impossible to play—a verdict which, coming from such an authority as this Saint Petersburg-based [Hungarian] virtuoso, plunged this unhappy child of my imagination into an abyss of what seemed to be irrevocable oblivion.”

“One day, some five years after my concerto had been written and published, when I was living in Rome, I went into a café and happened to pick up an issue of the Neue Freie Presse’s feuilleton section of which there was an article by the famous critic Hanslick

about a recent concert by the Vienna Philharmonic Society which, amongst other things, had also featured that hapless violin creation of mine which L. S. Auer had condemned to non-existence a few years earlier. Herr Hanslick reproached the soloist (who was none other than A. D. Brodsky)

for having made such a bad choice and lambasted my poor concerto, liberally strewing the pearls of his caustic humor and firing the most poisoned arrows of his irony. “‘We know, ’ he wrote, ‘that in contemporary literature there have started to appear works whose authors love to reproduce in detail the most repulsive physiological phenomena, including foul smells. One might describe literature of that kind as stinking. Well, Herr Tschaikowsky has shown us that there can also be stinking music [stinkende Musik].’”

“Tchaikovsky’s extraordinary first piano concerto was offered to Nikolay Rubinstein, to whom it was to be dedicated:

“I patiently played the concerto to the end: it was greeted with silence. I got up and asked, ‘What do you think of it?’ Suddenly a torrent of words gushed from Rubinstein’s lips, getting louder and fiercer every minute until he sounded like Jove the Thunderer. According to him my concerto was no good at all, impossible to play, with many awkward passages… so poorly composed that it would be impossible to correct them. The composition was vulgar, and I had stolen bits from here, there, and everywhere… I was not only astonished but offended by this scene.” When Tchaikovsky headed out of the room, Rubinstein noticed how upset he was and offered to play it if some changes would be made: “I won’t alter a single note, I shall publish the work precisely as it stands!”Having read the above comment by this famous and highly influential critic, I could vividly picture to myself how much energy and effort it must have cost Mr. Brodsky to get my ‘stinking concerto’ performed by the Vienna Philharmonic, and how aggrieved and unpleasantly struck he must have been by this attitude of a critic towards a work by a fellow-countryman and friend. Mr. Brodsky subsequently played the ‘stinking’ concerto everywhere, and was everywhere attacked by critics similar to Hanslick in their approach and their exclusivity of tone, but still the deed was done—my concerto had been saved, and now it is quite frequently played in Western Europe, especially since another excellent violinist, the young Karl Haliř, has come to the aid of Mr. Brodsky.”

Tchaikovsky’s extraordinary first piano concerto was offered to Nikolay Rubinstein, to whom it was to be dedicated: “I patiently played the concerto to the end: it was greeted with silence. I got up and asked, ‘What do you think of it?’ Suddenly a torrent of words gushed from Rubinstein’s lips, getting louder and fiercer every minute until he sounded like Jove the Thunderer. According to him my concerto was no good at all, impossible to play, with many awkward passages… so poorly composed that it would be impossible to correct them. The composition was vulgar, and I had stolen bits from here, there, and everywhere… I was not only astonished but offended by this scene.” When Tchaikovsky headed out of the room, Rubinstein noticed how upset he was and offered to play it if some changes would be made: “I won’t alter a single note, I shall publish the work precisely as it stands!”

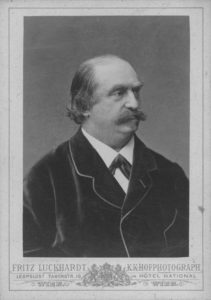

Vassily Sapellnikoff (1868-1941),

who plays Glinka’s song in a transcription by Mily Balakirev (1837-1910), became the first to record the Piano Concerto no. 1. Tchaikovsky wrote from Hamburg in 1888: “At the second rehearsal I was overjoyed at the sight of the triumph which fell to the lot of our young fellow-countryman V. L. Sapellnikoff. This young pianist had been invited—on the recommendation of Madame S[ophie] Menter (1846-1918), in whose class he had completed his course at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory—by the Hamburg Philharmonic Society to play my fiendishly difficult Piano Concerto No. 1 at the concert which I was to conduct there. Shortly before my departure from Saint Petersburg I had already had the opportunity to get to know Mr. Sapelnikov’s piano playing, but, although I had to a certain extent been able to w his wonderful qualities, all the distracting bustle which usually precedes a long trip abroad had prevented me at the time from realizing just how extraordinary the merits of this appealing young artist actually are.”

“Now, at the rehearsal, my delight kept growing in proportion as V. L. Sapellnikoff surmounted one after the other all the incredible difficulties of my concerto and gradually revealed all the power and all the qualities of his tremendous talent. And even more gratifying still was the way in which my delight was shared by all the members of the orchestra, who congratulated him enthusiastically at each break during the rehearsal and especially at the end. An extraordinary strength, beauty, and lustre of tone, an astonishing technique, an interpretation suffused by passion but at the same time a staggering degree of self-control preventing him from being carried away beyond the bounds prescribed by art, musicality, accomplished perfection, absolute confidence in himself—these are the distinguishing features of Mr. Sapelnikov’s playing. ‘Famos! unglaublich! Kolossal! ’– these exclamations were on the lips of all the musicians after the ovation which they gave him.”

Rachmaninoff ‘s evocation of Tchaikovsky’s Troika leads us to Anna Brodsky, wife of violinist Adolph Brodsky, who describes this pastime:

“These recollections [of being rejected in the West] are not very pleasant, and I much prefer to remember our sledging parties. No one but a Russian can fully appreciate the delight of these. We rode in a comfortable sledge, completely clothed in furs, fur coats and fur boots, furs above our ears, a fur cap, and a fur rug over our knees. Three horses were harnessed to the sledge, the middle one with a musical bell. We flew at marvelous speed over the steppes, fragments of snow were dashed in our faces, and endless stretches of snow were glittering and dazzling in the sun; the snow was absolutely virgin, and our sledge track was the first on its surface; the keen air cut our faces, but it was fresh and crystal-clear, and intoxicated like champagne. We returned home, glowing with health, and with the keenest appetite.”

Konstantin Igumnov (1873-1947) hardly knew Tchaikovsky yet became one of the composer’s finest interpreters and rose above the hostile factions between Tchaikovsky’s supporters and the Might Five, Balakirev as the guide for Borodin, Cui, Musorgsky, and Rimsky-Korsakov. Igumnov was born a year after Scriabin and one month after Rachmaninoff. His hometown of Lebedyan, south of Moscow, lacked decent musical instruction. Captivated by music at age four, a precocious development led him to be auditioned in Moscow by Nikolai Zverev (1832-1893),

a pianist and an influential teacher who had been taught by Alexander Dubuque (1812-1898), Field’s pupil, and Adolf von Henselt (1814-1889). Zverev had guided Alexander Siloti (1863-1945) and was teaching Sergei Rachmaninoff, (1873-1943) and Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) who lived with him. Zverev describes Igumnov’s audition:

“If he is going to play like this, then nothing will come of the lessons; technique will not develop. He must be put in order. If one can listen to him now it is only thanks to his ability, but if this ability were not there, this hand placement and manner of play would yield something quite impossible.”

Zverev prescribed Czerny studies, slow movements, scales, Beethoven, Weber, and after a three month period that began in late 1887 the fourteen-year-old Igumnov was accepted into the Moscow Conservatory’s senior ranks.

“It seemed to me (Igumnov recalled) that I was playing brilliantly. What kind of artistic plans could I have had then? I liked my performance. I assumed that I was doing everything more or less as it needed to be done. When I heard the pieces in my repertoire performed by other pianists I felt they were completely different, alien, utterly unlike the way they sounded in my interpretation. Something unfamiliar had been introduced into them – as, for instance, when I first encountered Taneyev and that element, whatever it was, was something I did not much like.”

In 1948, Igumnov’s pupil Yakov Mil’shteyn penned a necrology:

“With Igumnov’s death an entire epoch in Moscow’s musical life that has a connection with Taneyev, Rachmaninoff, and Scriabin has ended. He was a sincere and demanding artist. For him, a musical text was a kind of architectural draft, and according to this he built up the entire edifice of his performance from the bass to the smallest ornament. He couldn’t tolerate anything extreme, sharp, and excessive. His performance style was simple and laconic. He was diametrically opposed to the flashy playing so typical of other pianists, who used so much superficial contrast and effects that on the first exposure, it strikes one blind, and eventually it irritates us would as any spicy dish.”

“His playing was very soulful and poetic, was never given to excess. Very few could compete with Igumnov’s beauty of sound, unusual in its richness of coloring and remarkable singing tone. Under his hands the piano acquired the sense of a human voice which, due to his remarkable touch, merged with the keyboard.

“He always introduced something new into the interpretation of the piano literature’s chef d’oeuvres such as Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 111, Schumann’s Kreisleriana, Fantasie, Chopin’s B minor Sonata, Liszt’s Sonata, Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto, and piano pieces by Schubert, Chopin, Mendelssohn, Liszt, Brahms, and Rachmaninoff. His performances of these works reached the climax of pianistic art, but perhaps the most magnificent were his performances of Tchaikovsky’s music. Here he was peerless: there was such warmth and soul, so much tenderness, simplicity and chasteness. Igumnov’s teaching in no way followed a dogmatic teaching system, but he possessed a very surprising human and artistic sensitivity. He knew how to open and strengthen individuality in every student. Amongst his students, who were so different in their artistic aspirations, were pianists such as N[ikolai] Orloff, I[ssay] Dobrowen, L[ev] Oborin, J[akov] Flier, and M[aria] Grinberg. Not a single one among them ever lost their inborn individuality. Making great demands on himself, Igumnov was equally demanding towards his students. He was the docent who regarded them with great penetration and discernment when evaluating their power and ability. He constantly taught them the artistic truth, the simplicity and naturalness of expression, modesty, proportion and economy of means, the expressiveness of speech, singing, soft sound, plasticity and phrasing in relief. He taught them to reveal ‘life’s breath’ in musical performance.” (English translation by Joseph Stremlin).

When Henry Cowell (1897-1965) arrived in Russia in 1929, Igumnov headed the Moscow Conservatory’s piano sector. Samuil Feinberg (1890-1962) accompanied Cowell to meet the authorities at VOKS [All-Union Society for Cultural Contacts with foreign countries] who would grant permission for his musical activities. According to Cowell’s biographer Joel Sachs: “Henry soon discovered that the committee’s rejection was the best thing that could have happened. The word of his presence unleashed a stream of invitations to play privately for musicians. The first person to summon him was Konstantin Igumnov, a distinguished piano virtuoso and rector of the Moscow Conservatory. He does not say how he received Igumnov’s invitation, but Sidney’s [Mrs. Cowell] version is worth reading even if it is fanciful. At a very early hour, she says, ‘a young man came by and said the Director of the Conservatory had arranged for him to play for the faculty of the conservatory, very privately and “entirely safely”– inaudible from the street!’ There is no way to know if he was still sleeping on the bench, as Sidney thought. Impressed by Henry’s playing, Igumnov declared that the VOKS Committee was stodgy and overly cautious. He would back Henry and present him in concert. Such an action was, as Henry says, the equivalent of declaring musical war, because the committee was an official body whose decisions were normally final. Igumnov, however, had risen to the top of the profession, and as director of the conservatory, whose enrollment had swollen to 11,000 after private teaching was banned, he wielded authority. When he had Henry play for the faculty, his music created such a stir that he was asked to play for students. Those performances took place in relays, since there was no space sufficiently large and, if Sidney’s story is accurate, isolated from hostile ears. He began at four o’clock. ‘I played my first number for them, there rose from the hall an indescribable roaring and bellowing, like Niagara Falls and touchdown at a football game combined. Yells, shouts, clapping, and stamping of feet jumbled into one mighty din. The noise indicated neither approval nor disapproval, I think, but intense interest. When he had quieted the crowd and began the second piece, the noise resumed.’ A student delegate came forward and asked in German if Henry might play the first piece again, which he did again and again for half an hour. The session ended after four hours, when the hall was needed for another event. Students gathered around him to lament that he could not keep going.

Franz Liszt’s (1811-1886) influence permeated Russia through close pupils such as Pavel Pabst (1854-1897) and Alexander Siloti (1863-1945). Igumnov studied with both and recalls “I feel traces of the influence of Siloti on myself more than anyone else who taught me the piano.” A pupil of Siloti’s, the Russian-English conductor Albert Coates (1882-1953)

worked with a British spy to rescue the Silotis away from Russia after the Revolution. [ http:// arbiterre-cords.org/music-resource-center/alexander-and-kyriena-siloti/ ] In London, Coates premiered and recorded Scriabin’s Poem of Ecstasy. Alexander Borodin (1833-1887)

provided a scenario for In the Steppes of Central Asia: “The unfamiliar strains of a peaceful Russian song first waft over the uniform, sandy Central Asian steppes. We hear the sound of approaching camels’ and horses’ hooves, we hear the doleful strains of an Oriental tune. A native caravan passes over the boundless desert, guarded by Russian troops. It continues its long journey confidently and without fear under the protection of Russian arms. Farther and farther away the caravan recedes into the distance. The pacific singing of the Russians and the natives blends into a single harmony, whose refrain is long heard over the steppe until it, too, vanishes into the distance.”

One tale suggesed to Borodin and Rimsky Korsakov was Sadko, first proposed to Balakirev by Vladimir Stasov (1824-1906),

an art critic who acted as a guru for those eager to create a music derived from their native elements. “[Stasov] earned his living as a civil servant in the Second Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Chancellery and as a librarian at the Imperial Public Library in St. Petersburg. From 1855 Stasov worked in the Library as a volunteer and was promoted to the paid position of Head of the Arts Department in 1872, where he remained until his last days. The Library became Stasov’s invaluable provider of resources: he not only had access to all publications printed in the Russian Empire and a broad range of recent European books and periodicals, bur also was able to request that foreign press monitors send him articles related to subjects of interest to him.” Stasov wrote: “Anyone who wants to grasp Russian art, ancient Russian life, must start by putting out of his mind the wish to seek out with us anything resembling the Greek Olympus or the Greek gods. Neptune and company. With us everything is different, a quite different tone, different situations, different characters, different background, different scenery. Neptune in an izba! Neptune and the dance of the Sea King! Neptune a lover of gusli music! How unlike the Greek temper all this is, how it all goes against the habits and tastes of the European public, and of our apelike public as well! And meanwhile what new, fresh, colorful, succulent themes. What tableaux of Russian nature on the island of the Sea King, what themes of pagan antiquity, of ancient worship, of our ancient life, at the start, on the ship, then at the wedding feast, people and gods all together. And finally, at the very end, a tableau of old Novgorod and the river Volkhov – a marvelous subject, it seems to me.”

Borodin had trouble finding time to compose and finish works, a task assumed by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakoff (1844-1908).

Issay Dobrowen (1891-1953), conductor of the Polovetsian Dances,

from Borodin’s opera Prince Igor, profoundly influenced Ingmar Bergmann (1918- 2007), his stage hand in Stockholm where the exiled Dobrowen was producing operas. Dobrowen’s performances evoke a primordial ethos dwelling in the esoteric myths of the Orient.

Alexander Kamensky (1900-1952), an overlooked master,

found himself in Nikolaev’s class at the Petrograd Conservatory together with Sofronitsky and Shostakovich. He was one of the few to have recorded Musorgsky’s unknown Gurzuf at Ayu-Dag, a Crimean modal travelogue, its stark internal probing suddenly disturbed by a march that hides something painful under its mask of irony, an expressive device leading into a seeker’s psyche, a trait found in many of his works.

George Malko, son of the conductor Nikolai Malko (1883-1961) who was a peer of Stravinsky’s (1882-1971)

and fellow pupil of Korsakov, related an unscripted moment away from Stravinsky’s lifelong practice of fabricating an official version of what and how works were conceived and his encounters. Upon learning of his mentor’s death, Stravinsky grieved, repeatedly lamenting o Mme. Korsakov having ruined life. At a post-funeral gathering in the Korsakov Korsakoff apartment, as Stravinsky sat bent over, weeping, Mme. Rimsky-Korsakov approached, she placed her arm on his shoulder to comfort him: “There, there, we still have Glazunov,” which upset Stravinsky even more. One can hear what was stirring within Stravinsky when he conducted the Sadko Suite at a 1937 New York concert, a work composed when his teacher was a mere twenty-three, the same age as Stravinsky when he was Rimsky’s pupil. A critic focuses on what was probably unperceived by most listeners:

“Mr. Stravinsky directed the score with an accentuation of its youthful ardor. It was clear that here was a large talent trying its wings in exciting fashion. For Mr. Stravinsky, the performance of the work was probably a sentimental gesture in memory of his master, Rimsky-Korsakoff. That is, if Mr. Stravinsky’s recent protestations of absolute objectivity about himself and his art does not hold for the man who encouraged and instructed him when he was about the same age as was Rimsky-Korsakoff when this Sadko was composed. The program began with an earlier Russian work, Glinka’s Russlan and Ludmilla Overture. Here again Mr. Stravinsky made it clear that he appreciated fully the vitality and genius of his Slavic forerunners. The inner life of the music was communicated. Many musicians, including a generous representation of composers, were present yesterday. We are also fortunate that Stravinsky’s Fireworks was on the program and can be heard, conducted in a frenzy. Stravinsky intended to show the proofs to Rimsky-Korsakov who unexpectedly passed away before seeing it. Diaghiev was at its premiere, his first encounter with a composer who would soon collaborate with him on the Firebird ballet, leading onto a revolution that would transform the music world.”

Malko writes that “when Stravinsky went to hear Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936) conduct his own best-known ballet, The Seasons, Stravinsky recalled that in the green room after the performance Glazunov greeted him surlily. But this is not borne out by Glazunov’s own account of the meeting in a letter to Maximillian Steinberg, written soon after the event. ‘Stravinsky unexpectedly appeared,’ he reported, ‘and asked me whether I remembered him. Of course I recognized him immediately. He expressed his pleasure in the music of my ballet, and perhaps sincerely at that, since once long ago he asked me to give him the score to examine and didn’t return it for a long time.’ But Stravinsky’s sincerity can hardly have been much more than skin-deep, all the same; his real opinion of Glazunov was surely closer to that of [Arthur] Lourie [composer], who, on hearing a year or two later that Rimsky’s star pupil was taking a job in Berlin, inquired: ‘What can Glazunov teach them there? Perhaps the forgotten art of composing by tuning fork.’” Glazunov later became Shostakovich’s main composition teacher, having recognized his unique gifts and doing all possible to provide work and performances for his impoverished pupil.

On separate occasions this writer spoke with three ladies who attended Rachmaninoff’s memorial recital for Scriabin – Kyriena Siloti (1895-1989), Maria Safonov (1897-1989), and Vera Bushin (reached in 1987). All concurred that it was a noble gesture of Rachmaninoff’s but that he lacked a grasp of Scriabin’s style. Yelena Bekman-Shcherbina, who knew Scriabin well,

also observed that “[his] performance was characterized by an amazing finesse on nuances. The notation could not convey all the shadings, capricious tempo fluctuations, and the right tone. One had to read much between the lines, and the composer himself often changed the text.”

Prokofiev (1891-1953) was also there: “That same year [1915] I met

Rachmaninoff. He was very pleasant to me, offered me his huge paw and chatted graciously with me. That autumn he gave a concert in memory of Scriabin at which, among other things, he played Sonata No. 5. When Scriabin had played this sonata everything seemed to be flying upward, with Rachmaninoff all the notes stood firmly planted on earth. There was some confusion among the Scriabinists in the hall. Alchevsky, the tenor whom someone tried to hold back by the lapels, shouted, ‘Wait, let me have a word with him!’ I tried to be objective and argued that although we were accustomed to the author’s interpretation there could obviously be other interpretations. I was thinking of this when I remarked to Rachmaninoff after the concert. ‘After all, Sergei Vasilievich, I think you played it very well.’ ‘Did you think I would play it badly?’ replied Rachmaninoff with a wry smile, and turned away from me. This ended our good relations. A contributing factor no doubt was Rachmaninoff ’s dislike for my music, which irritated him.”

While these witnesses agree on how Rachmaninoff didn’t fully grasp Scriabin’s style, it is possible that the intensity and depth of his composing precluded any need to summon another’s approach. A trait that distinguishes their contemporary Igumnov is in the way he grasps and masterfully integrates their disparities by connecting them through the musical and personal levels that he developed during their mutual formation.

Igumnov also came to the rescue in 1895 when Scriabin wrote an etude (Op. 8 No. 8 ) and asked Igumnov to teach it to his girlfriend Natalya Sekerina. Scriabin was in Berlin on 15 August 1895 for the Anton Rubinstein piano competition. To Natalya, Scriabin writes: “We heard Igumnov play his solo piece magnificently.” All tied for first but a second round awarded it to Josef Lhevinne, with Igumnov receiving special mention. Igumnov also sent Natalya an observation: “Alexander Nikolaevich seemed emotionally unstrung and shattered… He gives the impression of a person who has nothing in the future, very little at present, and for whom everything belongs to the past. He says he is the happiest person in the world, but this doesn’t stop him from saying in the next breath that it is time for him to retire, that he wants to die more than an else, etc.”

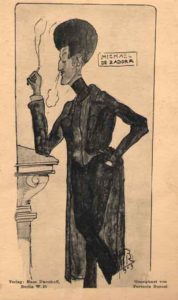

On the opposite front we have Prokofiev’s modernist tinge that dervies from Tchaikovsky; their pragmatic realism, originally an internalized process, would degenerate through Soviet cultural standards into being overt and blatant in its content’s interpretation. Michael Zadora (1882-1946)

catches the fervor of an early prelude. Many wondered why this Busoni (1866-1924) pupil always played with such gusto. But the daughter of the composer Vladimir Padwa, his colleague, described Zadora as high-strung, always placing them at risk as he might cause a scene at any moment.

These few examples of Igumnov’s Chopin and Scriabin come from one who understood how Chopin influenced him. This approach is carried further by Vladimir Sofronitsky (1901-1961),

who plays a Scriabin work on the instrument used by the composer during its creation. And where did it all lead? Tchaikovsky’s ballets dominate the stages, his virtuosity constantly being exploited into competition fodder. Balakirev’s circle led to the creation and spectacular close of the Silver Age, extinguished by Communist tyrants who imposed a dehumanized industrial aesthetic. Bely guessed correctly: “The whirlwind that is blowing in our Russia, swirling up all the dust, must inevitably create the spectre of a red terror, a cloud of smoke and fire, since light sets dust afire when it suffuses it.”

–Allan Evans ©2017

note: we make every effort to locate copyright holders of the photos posted. if we have omitted someone, kindly notify us regarding any necessary permissions.

Bibliography:

- Adlam, C. & Simpson, J. [eds.] Critical Exchange: Art Criticism of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Cenuries. (London. Peter Lang, 1992)

- Bely, A. Between Crisis & Catastrophe. (Kettering. Semantron, 2016)

- Bobrovnikova, O. Playing the Pathways of My Brain. (Bloomington. Author House, 2014)

- Bowers, F. Scriabin, a biography. (Mineola, Dover Publications, 1996)

- Brodsky, A. Recollections of a Russian Home. (London. Sherrat & Hughes, 1914)

- Igumnov. K. O fortepiannykh sochineniyakh P. I. Tchaikovskogo. (http://www.opentextnn.ru/music/interpretation. Accessed in 2016)

- Kimarskaya, D. The Natural Musician. (Oxford. Oxford Univ. Press, 2009)

- Malko, N. A Certain Art. (New York. William Morrow & Co., 1966)

- Malmstadm J, (ed.) Andrey Bely: Spirit of Symbolism. (Ithaca. Cornell Univ. Press. 1987)

- Milshteyn, Y. Nekrologi: K. N. Igumnov. (Moscow. Sovietskaya Muzyka, 1948)

- Prokofiev, S. Autobiography, Articles, Reminiscences. (Univ. Press of the Pacific, 2006)27

- Rusakov, Y. & Bowit, J. Matisse in Russia in the Autumn of 1911. (Burlington Mag. 1975)

- Sachs, J. Henry Cowell: A Man Made of Music. (Oxford. Oxford Univ. Press, 2015)

- Schimmelpenninck, D. Russia’s Asian Temptation. (International Journal, Vol. 55, No.4) – Russian Orientalism : Asia in the Russian Mind from Peter the Great to the Emigration. (New Haven. Yale Univ. Press, 2006)

- Tchaikovsky, P. Autobiographical Account of a Tour Abroad in the Year 1888. (accessed in 2017 on http://www.tchaikovsky-research.net)

- Walsh, S. Musorgsky and his Circle. (London. Faber & Faber, 2013)

- Weiner, A. By Authors Possessed: The Demonic Novel in Russia. (Evanston. Northwestern Univ. Press, 1998).