When you play, use your imagination,

make things happen.

This way the music will be alive!

– Ignace Tiegerman

Tiegerman: a memoir

Leila Birbari Wynn

To my dear Edward*, with lots of love.

I started taking piano lessons with Mrs. Bourkser in 1928 at the Berggrun conservatory on Shawarly Pacha St. no. 5, not far from Kasr el Nil St. It was a small villa with a garden. We took the Berlin [Hochschule für Musik] exams there. Mr. Tiegerman took over in 1932.

At a ceremony on the same premises the German ambassador, a tall, heavy man (Helmut Kohl-size) presented Mr. Tiegerman to us students, parents and the staff. As the ambassador bent low to shake hands with T., he apologized; “Pardon, je suis trop grand” to which Mr. Tiegerman replied in his charming way, “Non, moi je suis trop petit,” amid the laughter. I was sitting in the front row and was so struck by his style, his well-cut clothes and personality. By contrast, I remember Berggrun as an ordinary, ungracious person.

A few months later Mr. Tiegerman presided at a mid-term exam. All of us had to play a page or two from our program. One of Mrs. Lila Levy’s students played a primitive piece with a drum-beat rhythm (nothing to do with our program). We students were very embarrassed. When the girl finished playing, Mr. Tiegerman, who was sitting at a table with the rest of the staff in front of us, turned his head slightly and said in a loud voice, “ça manqué un singe,” this referring to the organ grinder on a Cairo street, always accompanied by his monkey who dances to the tune. We students were all amused but felt in awe of Mr. Tiegerman. I was surprised a year or so later when Mr. T. singled me and Mrs. Bourkser’s daughter as the two students he preferred in a student recital. My piece was Mozart’s Fantasy in D minor.

When we moved to Rue Champollion no. 5, there was another students’ recital at the Oriental Hall of AUC [American University, Cairo.] Usually after the exam (now we switched to the Warsaw [Conservatory] exams) we played a piece from the program in the autumn. Mr. Tiegerman selected a few of his students and myself to repeat the recital piece at the Egyptian Broadcasting Station: mine was Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C# minor, op. 3.

I left the conservatory for one year then came back to Mrs. Bourkser, took another Warsaw exam and passed without distinction this time. The next day, Mr. Tiegerman told Mrs. Bourkser that he wanted to teach me the following autumn. October 1938: I started my lessons with Mr. T. Canceling Mrs. Bourkser’s choice, he selected another program for the Warsaw exams: Mendelssohn’s Variations Sèrieueses, a prelude and fugue by Bach, 1st movement of Beethoven’s Concerto no. 3 in C minor, with the Reinecke cadenza, a study and a mazurka by Chopin. We started with the Mendelssohn and Beethoven, one or two pages at a time.

Mr. T. was very particular about the pedal. He spent a lot of time teaching me how to change the pedal after a chord in order to have a clean and sustained sound. “This helps you, also, to keep the rhythm and to memorize.” My hand was small, and I had a bad habit of stiffening my muscles. “Ne crispez pas” he would scream every now and then. . . My technique was the problem. Mendelssohn was my bête noire. In the middle of the year, T. flew into a rage, got up and banged shut the piano. I thought it would break. I was so shattered that I missed a lesson.

A month or so afterwards while playing Mendelssohn he said “ maintenant vous jouez comme une déese” as I looked up in surprise, he repeated the phrase in English, “now you play like a goddess.” During this time there were two Pleyel pianos in the room. He always played on one to correct us, or to show us how to play the phrase better. I loved the sweet sound of the Pleyel, especially when we played the concerto together. I felt secure playing with him.

Before the Warsaw exam in June, I played the study and mazurka by Chopin in a midterm exam. He surprised me when he said in a loud voice in front of everybody, “Vous meritez un médaille polonaise pour Chopin”, repeating in it English when he saw my surprised look. He was very encouraging. On June 24, 1939 I sat for my Warsaw exam which went so well, especially the Beethoven concerto, that Tiegerman remarked the following day [that] maybe I should specialize in Beethoven. Playing with Tiegerman made all the difference. Instead of being nervous, I relaxed and forgot myself. I enjoyed Beethoven so much that I finished well also in Chopin.

Tiegerman’s teaching was so clear and logical that by the time I reached the end of a piece, I almost knew it by heart. After the exam Tiegerman was happy to tell my mother “Elle savait son programme deux mois avant l’examen.” Before the exam (at the beginning of the school year, 1938) Mr. Tiegerman went over the Rhapsody in G minor by Brahms to improve it for the recital. (I had studied it with Mrs. Bourkser). The Bourse Egyptiènne covered the recital and among those selected I was mentioned as an intelligent interpreter of Brahms: the merit goes to Mr. Tiegerman.

During the second year with Mr. Tiegerman I had to study a Prelude and Fugue for organ by Bach-Liszt, the Pastoral Sonata by Beethoven [Op. 28], Papillons by Schumann, Ricordanza by Liszt. In the middle of the year Tiegerman was about to fly into a rage when he stopped suddenly and sat down, murmuring to himself “Maintenant elle aura une crise qui va durer deux mois.” [Now she will have a crisis that will last two months.] He remembered every little detail about us all. Once he told me “you notice the girl who comes after you for the lesson? She has big hands and can do anything with them. But no brains! If we could mix the two of you together we would have a very fine pianist.”

Then, when I started studying the Papillons he said, “Now, this is the sort of music you should play because of your hands, even though you are deep and dramatic.” Actually I fared better with Liszt’s Ricordanza. I played it in a midterm exam and he and the staff liked it. When I finished, he said “Vous n’avez pas un bon moment avec moi.” He was really happy and wanted me to play it at the recital during the coming fall but by that time I had decided to stop taking lessons. I simply could not go on working (teaching) and practicing the way I wanted to.

We became better friends and I continued to see Tiegerman regularly and attend all the recitals and local exams. In the forties (I think in 1945), Tiegerman, Aziza Hassanein, and her two nieces Jaida and Nagli and my family happened to be in Cyprus for summer vacation. I left Kakopetria for a few days and went to see Mr. Tiegerman on Mt. Trodos, staying in a hotel nearby. We used to have tea with Mrs. Hassanein every day while Mr. Tiegerman entertained us about some of his experiences, or talked about music and cooking (for instance how to marinate fowl.) He was always charming and relaxed, with a subtle sense of humor.

We also took walks in the forest. Once he invited me after breakfast to do the grand tour (all around the peak). We started promptly from his hotel (the only one made of wood in Trodos, mine was a camp hotel) in shorts and with walking sticks picked up en route. He always chatted, sometimes about musicians – Backhaus, Heifetz. . .”Of course Backhaus is very popular – he plays all the time” in answer to my question whether he was the Beethoven specialist. After a couple of hours Tiegerman admitted he lost the way back. “I always lose my direction” he said. My heart sank. We became silent. I was getting tired then, thinking I had hit him with my stick (he was leading the way) I said: “Pardon, Mr. Tiegerman!” “Pourquoi?” he asked. “I thought I had hit you with my stick.” “Non,” he answered, “perhaps you wanted to.” I was always charmed by his subtle humor.

Such a delightful person, with a special mind and a great personality, his playing was unique, very logical, sensitive, refined, and passionate, and his beautiful personal touch is unforgettable. Over the years I heard him play in several concerts and recitals. On his arrival in Cairo he played the two Chopin concerti at the Opera House (I was too young to fully appreciate his playing but I remember his touch.)

In the forties, during the war, he played Beethoven’s Fifth Concerto at the Empire Theater Ewad-el-Din which was broadcast. I heard it on the radio and can never forget the opening notes, his sensitive touch and flowing notes, the depth of the slow movement and the rhythm in the third movement. The beauty of the whole concerto was so striking and moving. No one has ever come close to this performance. Later at Ewart Hall (American University Cairo) I heard him play an all Chopin program: Sonata no. 2, Ballade no. 2 (Op. 38), Scherzo no.1 (op. 20), Studies Op. 10/10, 10/12, Nocturne Op. 37/2, Barcarolle. It was the most beautiful recital of Chopin I have ever heard, absolutely breathtaking.

During the war I strayed into Music for All when I saw Tiegerman’s name on a poster announcing a recital. I heard Schumann’s Davidsbündler played in such a way that no one could match the expression, rhythm and charm – absolutely unique. I left without hearing the rest of the program because the place was full of British troops and I felt out of place. (Later in Rome, I bought Arrau’s record and was so disappointed. It sounded like a set of exercises.)

In another recital I heard Tiegerman play the Third and Fourth Ballades, the Study Op. 25/11, always stunningly beautiful. And again I heard him play the sonatas Opp. 28 and 101 by Beethoven. I especially remember the singing style of the first movement. My escort, a British musician, said afterwards that it was the best rendering of this sonata that he had ever heard. In the late forties I heard Tiegerman play the Rachmaninoff concerto no. 2, so melancholy and intense. Later when I bought the record, I realized only Rachmaninoff playing his own music was a little better – no other musician was able to play this concerto so convincingly. I also heard Tiegerman play the Saint-Saëns Concerto no. 2 (not the ‘Egyptian’ and I must confess that it moves me less than Cesar Franck [referring to Tiegerman’s last concert].) His technique and fire were dazzling. We always said he played like a tiger. The last recital I heard Tiegerman play before I left for the U. S. in 1947 included:

Mozart: Rondo in A minor

Liszt: Liebestraume

Chopin: Etude Op. 25/1, Nocturne Op. 9/3,

Mazurka Op. 17/4, Scherzo Op. 54

No words can describe the poetry of this program, his performance and his interpretation.

He also used to accompany the students who sat for diploma exams. On top of staggering programs, each student had to play a whole concerto and Mr. T. played the orchestral part. I attended three of these exams, for they were open to the public. Mr. Tiegerman played the Tchaikovsky [1st], Rachmaninoff, and the Chopin second (orchestral parts). He could also play any solo part from memory, for he always taught us without the score and any orchestra part with the score. Nothing seemed difficult for him. Tiegerman liked to sit in the Groppi garden in the afternoons. Over the years I frequently saw him with Mr. & Mrs. Menasce, members of his staff and friends. He was always with Jicki, his beautiful German shepherd. When he arrived from Helwan and walked briskly into the building, Jicki followed him briskly too: he seemed to have the same gait as his master.

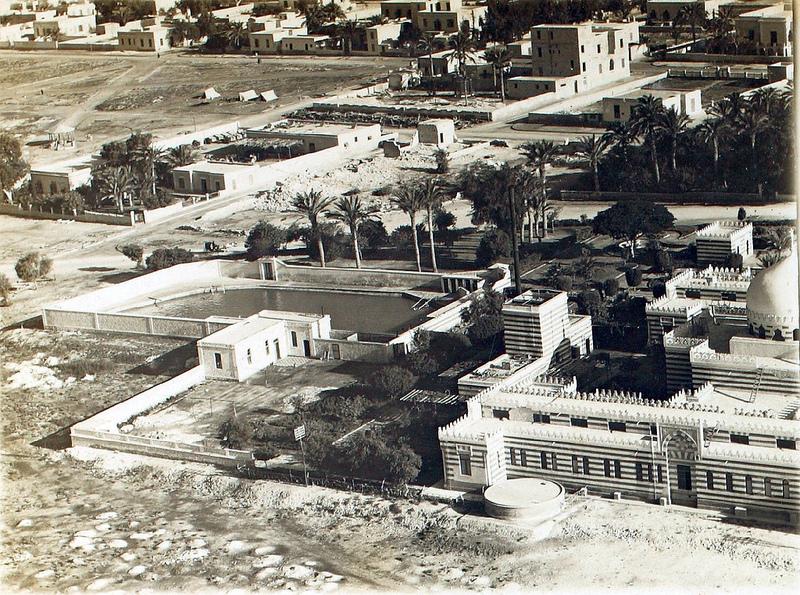

Before I would start my lessons every Saturday, Jicki would come into the room and hop onto the armchair. Tiegerman would caress and play with him for a minute or two. When Tiegerman stood up, Jicki understood it was time to leave the room. Then we would start our lesson. As far as I know, Tiegerman always lived in Helwan but had a couch in the room to the left at the conservatoire near the kitchen where he could spend the night if invited out or if he had to attend a concert. He usually had lunch in this room during the week.

After three years of absence I returned from the U. S beginning of October 1950 to spend a month with my family. Wynn [Wilton Wynn, journalist, Leila’s husband] came with me to meet Tiegerman for the first time. We had a wonderful visit and Tiegerman invited us for lunch at a hotel in Helwan, not far from his house (I only saw his house when you [Said] drove us to Helwan after dining with you, to accompany Tiegerman back home).

We were about to leave for the Sudan in a week (as Wynn had planned to do some freelancing in East Africa) and we discussed the Sudan with Tiegerman that day.

During the war in 1942 when Rommel had reached Egypt, Tiegerman and other foreigners fled to Khartoum and remained there, I think, one year, until Rommel was defeated. He lived in the Pension St. James, remembering its lovely terrace and rudimentary sanitary facilities that consisted of a communal bucket. He described the city as little more than paved strips surrounded by dust and prey to dust storms. Khartoum had sleazy cabarets where worn-out Hungarian blondes found rich Sudanese husbands. When we mentioned our upcoming visit to the Sudan, Tiegerman shook his head: “Mr. Wynn, I pity you!”

After a long trip in East Africa (Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Aden, and Yemen) we spent a few years in Beirut and returned to Cairo in 1955. I walked into the conservatory while a monthly exam was taking place and sat at the end of the hall to listen to some students play. As usual, Tiegerman would turn around and pick one, calling the name aloud. All of a sudden I heard “Birbari Leila.” He had spotted me and was looking my way with a mischievous expression. “Shall I play the Mendelssohn Variations, or Liszt?” He turned to the teacher sitting next to him, “Vous voyez comme elle a répondu vite!” It was his way of welcoming me back. During one of his visits for tea (at the Wahba building) he delighted us with an experience he once had in Spain, where he was invited to ride in a small plane. “As we were taxiing down the runway, I saw people frantically pointing at us. I looked down and saw a wheel rolling away. So I got up and tapped the pilot on the shoulder. ‘Excuse me, you have lost a wheel!’ The pilot put on his brakes and managed to stop the plane without a serious accident.” It was the first and last time Tiegerman attempted to fly. At a dinner in our house with the Canadian ambassador and his wife, the archaeologist Ahmad Fakhry and his blonde wife, Tiegerman charmed us by playing César Franck, then accompanying Mrs. Fakhry in German songs. The next day he telephoned to tell us how much he enjoyed the evening and added, “Mais le plus charment, c’était votre mari.” Once again he came for tea after having read Wynn’s book on Nasser (Wilton Wynn. Nasser of Egypt: The Search for Dignity. Cambridge, Mass., 1959): “Your book is very interesting, Mr. Wynn. C’est passionant. But in Europe, Nasser has a very bad press.”

In July 1956 Wynn and I went to Italy for a holiday. When Tiegerman knew we were going to Venice he gave us an appointment in piazza San Marco at 11 a.m. on a specific day. We walked around the square and found Tiegerman waiting for us in a café, sitting near a band. We had our cappuccino listening to the several bands playing at the same time around the square, then spent all day talking, walking around, sitting down for lunch at the Fenice Restaurant and later that evening, standing like Italians at a rosticceria, eating grilled mozzarella and drinking wine. Tiegerman loved Venice. He always stopped here on the way to and from Kitzbühel, staying at the Hotel Principe near the station. He knew so much about the rest of Italy. When he found out I was suffering from anemia he said, “Venice is wonderful for a few days, but you need mountain air for your health. Go to Merano in Alto Adige for a couple of weeks. You can take the train from here.” We did and I immediately felt better. He also could discuss the cathedrals in Italy. The one he liked best was the Duomo in Florence. He enjoyed being among Italians: “They are very spontaneous, not like the Austrians.” Once when we were standing up to eat and having wine near a young lady carrying a child, Tiegerman started giving the child some wine from his glass. The mother turned around and chatted with Tiegerman as if they were old friends. He loved Cortina d’ Ampezzo in Alto Adige: “It is one of the most beautiful spots in the world.”

After the Arab-Israeli war of 1956, thousands of Jews were forced to leave the country.Some of Tiegerman’s friends advised him to move to the U. S. At that time a lot of people were discussing a film featuring the American pianist Liberace, which Tiegerman had not seen, so I invited him to come with, since I too was curious. After Liberace played a few bars of classical music, he then got up to do a tap dance before going back to the keyboard. Tiegerman turned to me and said “I must learn to do this if I go to the United States.” Sometime in the late fifties, I heard one more student recital at Ewart Hall in which you too, Edward, had participated. You played the Chromatic Fantasie by Bach so beautifully and so professionally that Tiegerman got into trouble with his staff: he told me the day after that they were mad at him for letting you play. “Can you reproach a pianist for being too good?” Tiegerman hoped you would make a career in music. He admired you and was fond of you. In later years he always asked about you and mentioned you in his letters to me after I moved to Italy.

Before our move in 1961, Tiegerman invited us to the Conservatoire for a lunch that he himself had prepared, a chicken dish with a mushroom sauce. He was happy when I recognized the sauce’s base. It was so delicately flavored and tasty, I was so surprised at his ability to cook. [Tiegerman received a cordon-bleu in Berlin].

In August 1963, I went to Kitzbühel to see Tiegerman and spent five days in the house where he stayed, renting a room with an upright piano on the top floor.

At the last minute, Wynn had to do a cover story and could not come. Tiegerman was waiting for me at the station with a taxi that evening when my train arrived from Innsbruck. I used to go down to his room for breakfast. Before we went for a walk, Tiegerman practiced the Schumann concerto for one hour, a work he knew, mentioning that he was trying out new fingering. He worked on it for an hour in the afternoon. We spent the rest of the day walking, sometimes in the country, once in town and he took me up in the funivia to see the Grossglockner, the highest point in the Austrian Alps. He also showed me his cottage, which was empty at the time and said that anytime Wynn and I chose to come to Kitzbühel he would be happy if we would stay in his cottage as his guests. Once we were invited to hear music in the home of some friends, all Austrians. We used to have lunch in a nearby hotel and buy a light supper of cheese and honey from a shop to eat in my room, which had a table and a small balcony.

One morning Tiegerman invited me to his room while he practiced. He went through the whole book of Chopin’s Preludes (with the score). Every one was a gem, every note, every accent had meaning. I saw the preludes in a new light, the beauty and ideas behind them so uplifting. No pianist can come close to Mr. Tiegerman for the depth and interpretation of these preludes. When he finished, he closed the piano and said “Vous ferez une bonne femme pour un musicien?”

In 1965, Mr. Tiegerman sent me a card announcing his trip to Milan in late summer. He was supposed to record music. An ex-student Linette Tamim also came from Switzerland for the same purpose and we spend a delightful evening together. Next morning he came to see me off at the station and remarked “Je n’arrive pas à me calmer.” He was so touched that two former students would travel to see him for such a short time. Wynn and I kept inviting him to Rome and he seemed happy to accept but something happened each time that spoiled his plans. The last trip was cancelled because of the 1967 war. I telephoned him and he was very upset about not being able to get a return visa [Tiegerman had Polish citizenship].

In late summer of 1968, I accompanied Wynn to Cairo. I went right away to the Conservatoire to greet Tiegerman and found the place all sealed up. The bowwab (doorman) informed me that Mr. Tiegerman had died in May and the government was awaiting his niece to settle his affairs and pay taxes in arrears. [According to Tiegerman’s niece Hedwika Rivalova, the accounting secretary ‘neglected’ to pay the school’s tax]. I was shocked and the bowwab sent me to speak with Mrs. Menasce around the corner. It was hard to accept his death.

Wynn and I returned to Cairo and sometime in the summer of 1974 and I went to the Jewish cemetery to search for Tiegerman’s tomb. Wynn let me have the Time [magazine’s staff] car and driver and one of my cousins accompanied me. The old section of the cemetery was all broken up and had been defiled (I was told) by mobs after the defeat of the Egyptian army in the ’67 war. After a long search I found Tiegerman’s tomb intact, in the new section,

It was a very barren and dull part of the cemetery with only slabs of stone, level to the ground, all alike, side by side, no vegetation, no variety, no soul. It was sad to see a person like Tiegerman, who was so sensitive to beauty and who had a very warm and rich personality, buried in a barren, lonely, and soulless plot. The inscription read:

Ici repose un grand pianiste

Ignace Tiegerman

directeur du Conservatoire de Musique au Caire

1893 – 1968

*Dedication to Edward Said,

piano pupil of Leila Birbari Wynn before he studied with Tiegerman. Our gratitude to Leila Wynn and Maryam Said for providing the manuscript.

©Arbiter of Cultural Traditions 2019

For those who have read this far we posted this memoir in expectation of a newly discovered folder containing a photo of Tiegerman with Jiki, a German shepherd given to him by King Farouk as well as, ahem, unknown manuscripts of his own compositions. Stay tuned and don’t forget we’ve published his recordings.

Allan Evans