He would enter dressed like a CIA operative who tried to act inconspicuous while delivering internal espionage capers. Sunglasses shielded his eyes as he hypnotically intoned texts with precise metrics that supported his myths. Robert Ashley’s half-sung narrative practically breathed down the neck of his subjects, coming as closely as one ever could to their physical presence while suddenly leaping out into a divine perspective via altered states of phonemes and consciousness.

Ashley began composing dissonant academic music but that soon gave way to electronics and his gift for writing led to texts that place him as a Faulkner of the Corn Belt:

. His greatness as a writer rivals and often surpasses his musical ideas.

This in-and-out of mundane and divine regions was traversed at the breathtaking speed of a rapid voiced volley of overlapping cosmic ironies. To hear Ashley speak of his passion for reading financial journals in order to ferret out their hermetic language and how he could embed it in his works brings us within the workshop of his ingenious creations and how they and he acquired an identity.

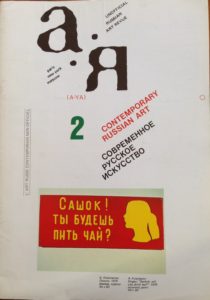

As the Soviet Union was thawing in 1990, more individuals were able to travel outside the Iron Curtain for the first time. When I came there in 1987, the U.S. Embassy’s cultural attaché had a rolodex with phone numbers of the underground cultural protagonists. Artists were plied with Russian publications such as A-Ya, a magazine covering work of emigrées, defectors or busy away from the censors. Printing on heavy paper was essential as copies had to reach to hundreds of readers, hand to hand on the samizdat network that kept everyone informed of what the official media prohibited. According to Elizaveta Butakova of the Courtauld Institute of Art, London

“A-Ya was a tri-lingual magazine published in Paris from 1979 to 1986. Published in Rus- sian, French and English, it featured contemporary non-conformist Soviet art of the period and was edited by the unofficial sculptor Igor Chelkovski, who had emigrated to Paris in 1976. A-Ya featured some of the most important Russian artists of this period, including Ilya Kabakov, Eric Bulatov, Oleg Vassiliev and Komar and Melamid, and yet its importance has been understated.”

Our diplomats paved way to collectors, underground musicians, jazz fanatics, a classical musician banned from playing in major cities but cosy with a housekeeper whom he impatiently kvetched at to hurry up with our tea, and pianist Sviatoslav Richter’s sexy assistant (Georgian-Ukrainian) who received me in his apartment on Bol’shaya Bronnaya Street while he away in Germany.

Dmitry Ukhov spoke faultless English and was as up to date as anyone in the US on the Jazz scene, an avid listener to and familiar with Indian raga scales, classical music old and new and more. On the morning of a lecture scheduled to introduce Russian composers to Ashley, David Borden, Steve Reich, Arnold Dreyblatt, La Monte Young, and John Zorn at the House of Composers, an early phone call informed that I was not to present any new music but instead bring over the guitar and cover American Blues and the music by Reverend Gary Davis. It was a genre rife with anti-authoritarian messages that the older male caryatids couldn’t detect. Suspecting this to be a power-ploy cooked up by their malignant cultural tsar Tikhon Khrennikov, a Stalin-era apparatchik-composer assigned to serve as Shostakovich’s official antagonist, Dmitry and I first stopped down the street near Dom Kompository to pick up two elderly sisters. Ukhov kindly shlepped my guitar while I hooked one sister onto each arm in dry, invigorating zero-degree weather. The composer nomenklatura did not seem particularly happy when recognizing that Scriabin’s two daughters were smilingly accompanying the American. These were the people who purged many of their friends. A photo album had many faces cut, for to have them recognized after their deportations would have risked the sisters’ lives.

Elena Scriabina Sofronitskaya had been Vladimir Sofronitsky’s wife and is seen in a documentary of Vladimir Horowitz’s return to Moscow, the memory of which was still shuddered over by the US embassy’s staff, recalling how the maestro’s windows had to be covered with mylar to prevent any light from entering his bedroom at Spasso House, the Ambassador’s residence and how his mandatory Dover sole had to be flown in fresh, daily from Helsinki, whisked through their diplomatic pouches and rushed over by an embassy driver to the main kitchen.

Ukhov’s New York arrival was timely as Phil Niblock’s Experimental Intermedia Foundation was hosting the debut of clarinetist-composer Roberto Paci Dalò from Rimini, Italy. In the audience were John Cage, Leroy Jenkins, and several other composers and performers that Ukhov had only heard on clandestine recordings. After a slight nudge he approached several and appointments were eagerly made as his presence was a novelty at that time. I tagged along and one visit yielded a few inspiring hours with Robert Ashley at his Tribeca loft, a time when that area was industrial and largely uninhabited. Here’s the conversation that ensued on a December day in 1990:

Part I:

Part II:

A book that keeps Ashley close by:

Allan Evans ©2016 with gratitude to Dmitry Ukhov.