Track List

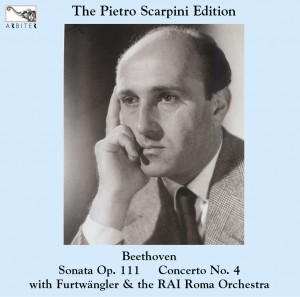

Beethoven Sonata op. 111; Piano Concerto no. 4 with Wilhelm Furtwängler & the RAI Roma Orchestra. Pietro Scarpini was a founding Modernist in Italy's pianistic traditions, one whose performance of Schönberg's Pierrot Lunaire astonished John Cage. His approach to music is guided by a deep probing intellect finding a unique stylistic projection. Our download album contains as a bonus Scarpini's performance of Beethoven's Piano Sonata op. 13.

- Beethoven Piano Sonata op. 111: I

- Beethoven Piano Sonata op. 111: II

- Beethoven Piano Concerto no. 4, op. 68: I

- Beethoven Piano Concerto no. 4, op. 68: II

- Beethoven Piano Concerto no. 4, op. 68: III

- bonus download track: Beethoven Piano Sonata op. 13: I

- bonus download track: Beethoven Piano Sonata op. 13: II

- bonus download track: Beethoven Piano Sonata op. 13: III

Italy’s finest singers have been adequately represented on recordings, yet its most significant pianists have been eclipsed to the point that they remain virtually unknown. The first Italian pianist to have recorded was Giovanni Sgambati, Liszt’s pupil, who taught in Rome. Sgambati recorded chamber music with his trio for G&T in London before 1910, but their discs were never published and have yet to be found. One early international virtuoso was Maria Carreras (1877-1966), who studied with Busoni. Only in 1999 were test recordings of Carreras playing Brahms discovered. Carlo Zecchi (1903-1984) a pupil of Busoni and Schnabel, abandoned the piano in favor of conducting and chamber music, for which Zecchi proved to be a grand master. His meagre recorded legacy offers mere glimpses of a major artist whose pianism was inadequately documented.

The case of Pietro Scarpini (1911-1997) is unique, as he was a peerless and profound musician who developed a rareified and vast repertoire. Scarpini was the leading pianist in Italy after World War II, yet has not received proper recognition due to his disdain for recording and for having avoided the public sphere which artists are compelled to engage in, as Scarpini chose to live for his art and deliberately avoided outside intrusions on his life in order to maintain and cultivate his musicianship. Paradoxically, while he did little to preserve his art through commercial recordings, Scarpini methodically kept tapes made of recitals and broadcasts and added to it by recording at home.

Scarpini was a leading figure in Italy, Germany, England, and for a brief period, in the United States, known for performing works such as Bach’s Art of the Fugue, Goldberg Variations, Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, Scriabin’s late works, and gained prominence for championing the works of Busoni and Schonberg’s Pierrot Lunaire. As a concerto performer, Scarpini had worked with an array of conductors including Furtwängler, Van Kempen, Böhm, Monteux, Horenstein, Mitropoulos, Rodzinski and Szell and played chamber music with the Vegh Quartet, Paul Hindemith, and Marya Freund among others.

Scarpini’s one solo recording, made for the Durium firm around 1950, was characteristic of his musical focus: sonatas and shorter works by Bartok and Stravinsky. One regrets the absence of the Goldberg and Diabelli sets, as Scarpini often performed them before the 1960s: perhaps they will be discovered some day.

The Pietro Scarpini edition will represent all of Scarpini’s major surviving musical documents, including works by Bach, Bártok, Beethoven, Borodin, Brahms, Bruckner, Busoni, Chopin, Clementi, Couperin, Dallapiccola, Debussy, Gershwin, Haydn, Janacek, Liszt, Mahler, Mozart, Prokofieff, Rachmaninoff, Rameau, Scarlatti, Schönberg, Schubert, Schumann, Scriabin, Stravinsky and others, made from 1938 (a private disc of a Liszt paganini Etude) to home recordings taped after his retirement in 1971.

As only two or three interviews with Scarpini exist, along with two musical commentaries, primary sources are extremely limited, obliging the forthcoming discs to reproduce them along with critiques and many examples of his programs. Amongst his papers was found one revealing document: on an undated page on hotel stationary, Scarpini typed in English an overview of the significant events in his career:

Principal training:

Piano (Casella); Organ (Germani); Composition (Bustini, Hindemith); Conducting (Molinari) Rome University (Ph.D. in music history).

Debuts:

Rome [Nov.] 1937 (Molinari conducting the S. Cecilia Orchestra); Mozart Concerto K. 271 and 1st performance in Italy of Rachmaninoff Paganini Rhapsody (meeting Richard Strauss after the performance of the Mozart Concerto)

New York 1954 (Mitropoulos conducting the N. Y. Philharmonic) Prokofieff 2nd Concerto.

Creations and major first performances:

1938 creation of Hindemith Sonata 4 hands (with the composer playing the ‘Secondo’ part, Florence)

1943 creation of Dallapiccola Sonatina canonica, dedicated to P. S.

1946 1st performance in Italy of Prokofieff 7th Sonata (Venice International Festival)

1949 1st performance in Italy of Schönberg Piano Concerto (with F. André, Turin S.O.) 1952 1st performance of the complete piano works of Schönberg (Rome, S. Cecilia)

1963 1st performance of many unknown later works of Scriabin in a retrospective recital dedicated to him (Venice International Festival)

Landmarks:

1952 Beethoven 4th Concerto with Furtwängler (Rome RAI SO)

1954 1st (?) integral performance of Bach Art of Fugue (original text) in New York

1956 Mozart Bicentenary Cycle in New York (Concerto K. 482 with Mitropoulos & N.Y. Philh.)

1958 Busoni Sonata with Joseph Szigeti, Empoli – Fantasia contrappuntistica in Berlin and London

1960 Bach’s 48 [Well Tempered Clavier], York Festival

1966 Busoni Centenary 1st performance of Concerto op. 39

(with Szell & Cleveland SO) in Cleveland and New York

Editions:

1951 Mahler 10th symphony – deciphering and arr. for 2 pianos, both recorded by P.S. for a broadcast (meeting with Bruno Walter in Florence 1952 for matters concerning this symphony and its orchestration)

Appointments:

1939-1971 Florence, Milan, S. Cecilia Conservatories

1948-50, 1968-71 Siena, Accademia Chigiana

1950 Darmstadt, International Ferienkurse

Ensemble:

‘Pierrot Lunaire ensemble’ (Schönberg) conducted at the piano by P.S. founded 1947 (including among others Marya Freund, Severino Gazzeloni) 36 performances over all Europe.

[Scarpini added in the margin:] The statement in the Grove’s Edition 1954 (signed M.K.W.) “he plays in a pianoforte quintet” is erroneous.

I am the Rubinstein of Contemporary Music

For his love of modern repertoire, pianist Pietro Scarpini prefers whistles to applause.

by Giovanni Carli Ballola

A recital by Pietro Scarpini, the pianist who has placed his own art in the service of music from the 1900’s, is always replete with stimulating modernity, even when the concert artist sits at the keyboard to play masterpieces of the past. Those who know Scarpini and his artistic undertaking, immersed up to his neck in problematic contemporary music, know that his Bach and his Beethoven cannot be the usual works fished out of the repertoire of each pianist, but will be, on each occasion, that specific Bach and specific Beethoven who for their interpreter don once again a significance full of contemporaneity.

Thus even this time, in concerts held in Turin and Milan during a brief Italian tour, the apostle and divulgator of the piano works by Schönberg and Berg, by Prokofiev and Busoni, has performed among others two of the most transcendental and mysterious works of Beethoven the Diabelli Variations and the Six Bagatelles, Op. 126; a revealing selection in the way they represent a Beethoven vertiginously foreshadowing and acting as a bridge, boldly jumping beyond the 1800’s to leap into our own century.

How did it happen that Pietro Scarpini became nearly the only pianist of his generation to systematically undertake the difficult path of contemporary repertoire? “It might be explained”, the pianist replies, “by the fact that I was born to be a composer and conductor, and then I became a pianist by chance.” Born in Rome in 1911 to a father who was a General [in the Italian Army before World War I] and music lover and to a mother who was a pianist, Pietro Scarpini already knew at age four how to play the piano and gave his first recital at six. What followed came in a life which moved at a record-breaking pace: granted a diploma in piano at age twelve (he was a pupil of Alfredo Casella), diplomas in composition and organ at eighteen, and two years later a degree in literature. But this was not enough: at twenty-two, Pietro fell in love with the young Austrian pianist Teresita Rimer, and married her.

His career seemed oriented towards leading an orchestra. Bernardino Molinari, his teacher, considered Scarpini as the most worthy successor possible and offered him invaluable advice until a fortuitous event changed his destiny. One day during a conducting lesson, Molinari asked who among his students wished to play, for better or worse, the solo part of a Rachmaninoff concerto which would serve as a runthrough before a full rehearsal. “I came forward” Scarpini recalls, “not because I wished to distinguish myself from the others but rather to please the teacher. While I thrummed on the piano under the direction of a fellow student, I noted that Molinari was following me with attention and growing amazement. At the end of the work he came up and slapping his hand on my shoulder, he said to me, ‘A good conductor, you could become but a pianist, rather, an excellent pianist, you already are.’ [Un buon direttore d’orchestra lo potrai diventare, ma un pianist, anzi un eccellente pianista lo sei di gia.]”

Following his teacher’s exhortations, Scarpini came forth again as pianist: he was invited to Berlin to give a series of concerts with the Philharmonic Orchestra under Furtwängler. [note: Ballola confuses the facts here. Scarpini did make an early appearance in Berlin, but not under Furtwängler. Their sole collaboration took place later in Rome with the Beethoven Fourth Concerto heard on this disc. The encounter with Furtwängler which Ballola cites might be from their concert in Rome or perhaps results from a reporter taking liberties. We hope to clarify this in the future, if possible.] With the great German conductor, Scarpini had repeated occasions on which to play, and each time Furtwängler praised him further, causing the young pianist’s cheeks to burn with emotion. Soon after, this pupil of Casella threw himself headlong into the study of 20th century repertoire of which he would become an impassioned and intrepid popularizer.

Good doses of courage and self-effacement were needed to present oneself to a biased public, to sit at the keyboard with certainty and arise at the end to a hurricane of whistles and boos. For many years Scarpini made his entrance into the concert hall with the spirit which an apostle of a creed would have when entering an arena of ferocious beasts about to tear him apart. For many years, he smilingly confronted a public which asked itself how was it that a pianist of his calibre persisted in playing ‘impossible’ music. Among those who asked himself such a question more than once was old Alfred Cortot, who greatly admired the young Italian colleague: each time when Scarpini played in Paris, even if Cortot understood nothing of what was played [Ballola curiously underestimates Cortot. tr.], he applauded Scarpini and intimidated a public prone to hostility with his authoritative stance.

The battle years have passed: Prokofiev, Berg, and even Petrassi and Dallapiccola have become classics in the music of our century, which promotes an experimentation that is or wishes to be more unshackled from the past, even the recent past. And for Scarpini, the revolutionary pianist of the Forties, destiny has had a surprise in store: his new status today as a traditionalist, a conservative. “The young avant garde find me a type of Backhaus or Rubinstein of 20th century music”, he comments, amused, but not without a touch of melancholy, “and they’ve made me understand it respectfully, but unequivocally the last time I took part in the summer courses at Darmstadt, the annual fair of the latest prototypes of musical extremism. But now I don’t feel like betraying Schönberg for Cage, Boulez or Stockhausen. And furthermore, if I must speak truthfully, I have too much respect for the public and for my instrument to be able to scratch the strings with a shoe or punch and kick it.”