Just gave a class to Mannes grad students on Chopin. So much attention focuses on his Parisian existence that his Slavic origins are slighted. Half-French/Half-Polish they say? Which half is Slavic? How do you cut him: vertically or horizontally? Let’s bypass Solomonic butchery to say that he possessed 200%, enriched by both!

Chopin composed Mazurkas throughout his life, a workshop for ideas and connecting with a lost homeland yet most judge them as exotic seasoning sprinkled onto formal salon Waltzes. Do you think that notation shows everything? Mazurkas only appear on paper as waltzes yet bear disruptive chromatic notes. And what does a village ensemble from the mountains outside Sofia have to do with Chopin?

The Balkans and Central-Eastern Europe were pervaded with folk music that identified itself through distinct melodies and rhythms. The Bistritsa Grannies sing antiphonally, replete with stark intervals that came from origins way further East, possibly the Proto-Bulgars from Central Asia.

In 1987 with a group from the National Conservatory that included the budding composer Penka Kouneva

they received us after a day’s farming to offer singing and supper. Changing out of their blue work smocks they regrouped in traditional attire. Afterwards we scooped up local sirine (feta cheese) with bread dipped into chubritsa, a Bulgarian spice blend redolent of fenugreek with other subtle herbs. An LP recorded for Balkanton contains this work and when I met up with them three years later when their dictatorship had been quashed, asked what the meter was in their song Oreovka voda grebe : “Two”.

Two, certainly, but the beats are unequal, with long-short pulsations. This brought to mind the Hungarian accenting in their folk-Gypsy traditions. One daring team of Budapest ethnomusicologists penetrated into Romania’s Transylvanian region to secretly record Hungarian dance music, as their insane dictator did all he could to suppress anything that could heat up any justifiable revanchism. A battery-operated tape recorder had been hidden in their car and here is a treasure from a remote village in the Mezöség region:

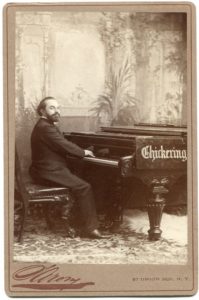

So with these rhythms and phrasings circulating in your system, how could Chopin have played his own ‘colorful’ works? The earliest pianist who offers a clue is Vladimir de Pachmann (1848 Odessa – 1933 Rome).

A Victor Borge of his time, Pachmann amused audiences through chaotic inappropriate behavior and speaking while playing, probably done to settle his nerves and placate a public that wanted more than music alone, a format then unknown. Critics downgraded him as someone pathetically superficial for having spoken on some of his recordings that had unedited sloppy details whereas the early butchered restorations of his playing (recordings from 1907-1928) were dim and masked any and all of his colorful nuances. As technology improved, a remarkably chaste art emerged, thanks to a discovery I made by finding a path to access the hot-spot in groove walls, where the sound fully opens up, one surpass routine sardine-can transfers that obliterate hear color and touch. On interviewing Aldo Mantia in 1981, a Roman Pachmann pupil, Mantia mentioned that his mother, a singer who knew Liszt, recalled with singer Luisa Tetrazzini how the young Pachmann had lived in Firenze for six months to study with Vera Kologrivoff Rubio, Chopin’s last assistant, an important detail vigorously denounced in a recent puerile biography of the artist.

Note how Pachmann accents and uses short-long beats in Chopin’s Mazurka Op. 50, No.2 in A flat, recorded into a horn in 1911:

No waltzing at all and if accurately transcribed, the writing would be unreadable. Chopin published these pieces early on up until his end. His F-sharp minor Mazurka, op. 59, No. 3 is a hotbed of experimentation. Starting with a straight-forward dance, it returns with a secondary voice under the main theme and then switches into major. What impresses as hackneyed confused playing is a literal representation of something unique in Chopin’s notation: rhythmic displacement of the hands by a mere sixteen note that syncopates them into a duel of phrasing and accents. Pachmann knowingly displays this radical stratagem within the guise of propriety. To dissipate its rhythmic angst, Chopin aligns hands into a pattern that furiously repeats and changes from three beat segments into twos in order to eradicate the previous tension. What next? Canonic imitation, a return, and a finale in a contrasting dance rhythm.

Again we join Pachmann caught by a recording horn inside a Camden, New Jersey studio in 1912:

Going further through Chopin’s backdoor we encounter a master who danced with villagers when his father took the boy along for gigs in remote towns. These experiences, along with a life-long penchant for Mannerism (in art and sound) leads us to Ignaz Friedman (1882 Podgorze/Krakow – 1948 Sydney).

Friedman astonished listeners with his Chopin and fortunately the obtusity of his record company lapsed when they unexpectedly commissioned him to record a set of the dances rather than continuing having him fulill their need for encore pieces. We find him before the microphone in London, 1930. Chopin’s Mazurka Op. 7, No.3 in F mine:

‘

The rhythms are far more extreme and we note the strong presence of folk elements into the otherwise hermetic classical music that sought to keep out such roughage, still unacceptable in today’s puritanical climate in which budding pianists cannot compete by playing with individuality or stray from the moribund status quo’s dictates.

Friedman possessed a remarkable virtuosity that allowed him to laugh away technical difficulties. He tickles Chopin’s 19th Prelude in E flat and calmly navigates the treacherous G# minor Etude, back in 1924:

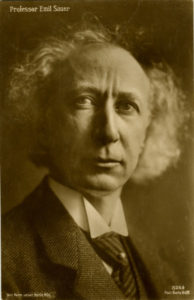

When Emil Sauer (1862 Hamburg – 1942 Vienna)

met Brahms, they shared their origins as Hamburgers. Inspired by his teachers Nikolai Rubinstein and Liszt, Sauer also composed and brings out the inner life dwelling in the otherwise mechanically played Chopin Etude, Op. 25, No.12 in C minor, recorded when the pianist was 78 years old.

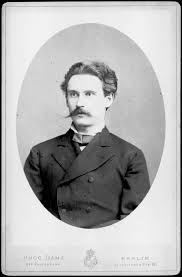

Going beyond virtuosity we can hear poetry in a posthumous but well known work, Chopin’s Fantasie-Impromptu, Op.66. Polish pianist and composer Xaver Scharwenka (1850 Szamotuły, Poland – 1924 Berlin)

plays with a creator’s insight into the music, displaying all elements and in the slower middle section, bar lines melt to allow a commanding melody to bask in a rubato that is subtly camouflaged. A 1910 New York studio recording is restored to the point of displaying his colorful touch and identifies the piano as a Steinway:

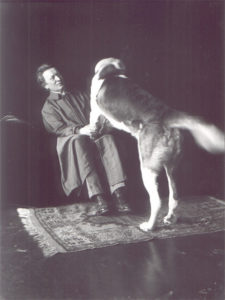

Running out of time. Here’s Ferruccio Busoni (1866 Empoli – 1924 Berlin), seen during exile in Zurich with Giotto his San Bernard,

playing a Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody (No. 13) with full awareness of the Gypsy phrasing in its final section, recorded on a Beckstein in 1922, London. We’ll get to his way of deconstructing Chopin next time.

For further exploration check out the Pachmann trail on our website

www.arbiterrecords.org

Pachmann’s son Leonide interviewed in French:

Friedman and his peers astonishing with their Chopin:

Allan Evans ©2019