In 1993 a celebration of Edvard Grieg’s 150th birthday was being organized at a conservatory where I was teaching. Young Norwegian musicians were to be flown in to New York and perform his works and the organizer, a trombone teacher, was taking care of the details. At that time I located a record collector willing to share his own copies of recordings made by Grieg himself in a Paris studio one day in 1903. Their rarity is such that some exist in one known copy, a pathetic oversight when considering how many of Grieg’s recordings by others flood the market and airwaves to leave his own playing unknown and inaccessible. I proposed playing them with some words, a half hour at most, unpaid. “It’s not relevant to the occasion” was his professional way of saying “Get lost!”

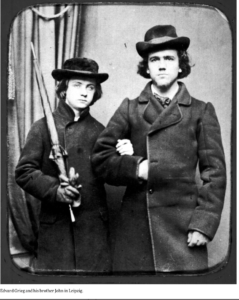

Grieg was probably ill at ease when he and his brother (taller, on right) left their town of Bergen to arrive in the imposing prestigious university city of Leipzig, where Schumann’s colleagues were still about and teaching, imprinting the influence of their colleague who had passed away nearly a decade earlier onto a budding composer from the far North who was to perfect a classical training that nourished an ongoing empirical contact with his country’s folk music, a trait not lost on later pioneers of ethnomusicology such as Bartók.

While some one or two hundred in the 1993 audience heard what they were permitted to hear, we can now bypass their shortcomings by offering Grieg’s complete piano recordings made on discs – not gimmicky inaccurate piano rolls – for listening by anyone daring to click below. These nine works were mostly composed decades earlier and still reveal an enthusiasm that evokes the joy of inspiration by making a sonic objet trouvée or folk-based tune into a solid masterpiece miniature. Here is his legacy in sound, arranged via the playlist:

- Alla Menuetto, from Sonata in E Minor, op. 7

- Finale (Molto Allegro), from Sonata in E Minor, op. 7 (abridged)

- Humoreske in G-sharp Minor, op. 6, no. 2

- Norwegian Bridal Procession, op. 19, no. 2

- Lyric Pieces: Butterfly, op. 43, no. 1

- Lyric Pieces: To Spring, op. 43, no. 6

- Lyric Pieces: Gangar (Norwegian Peasants’ March), op. 54, no. 2

- Lyric Pieces: Wedding-Day at Troldhaugen, op. 65, no. 6 (abridged)

- Lyric Pieces: Remembrances, op. 71, no. 7

recorded in Paris, 2 May 1903 on an upright piano.

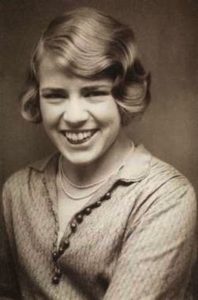

The pianist-composer and his singer-spouse Nina, at home in Bergen, Norway:

During a two-decade-plus Ignaz Friedman hunt, I spent several days in Oslo unearthing interviews, programs before sailing back to Copenhagen with a thick folder. Friedman stuck out First World War there, using diplomats to smuggle supplies to his wife and daughter back in Berlin via unchecked diplomatic pouches. Copenhagen’s numerous archives sprung up leads almost daily. One of the Norwegian clippings mentioned that the pianist Ingebjørg Gresvik had spent a summer with Friedman studying at his home in Siusi, above Bolzano, Italy in the Dolomites. She was listed in the Bergen phone book and after our chat I sailed at once back to Oslo and grabbed a night train to cross Norway and reach its western shore. As soon as Gresvik opened her door there was absolutely no way that any time could be spent elsewhere in Bergen: adieu to seeking the Grieg house, museums, their old town. Her warmth and enthusiasm in having been sought after brought out a spontaneous camaraderie that had to eliminate all else. I ended up staying as her guest for two days.

Gresvik was then 76 years old and once inside she opened onto many worlds. I left a tape recorder running finds her describing the Friedman she knew in 1935. Although she had been out of practice for over a decade, her soulful witty playing won me over as did her memory and modest insight. (photo: Gresvik in traditional dress)

Her words were casually taped in May of 1985 and much off-mic comments were noted, especially her closeness to the composer Sinding. By starting with her portraying Friedman as the first well-known touring pianist to annually tour Norway and become a national favorite, many doors opened as Gresvik recounted Ibsen’s daughter, a Berliner friend who was a relative of Walter Rathenau, and her studies with pianist Edwin Fischer in Potsdam.

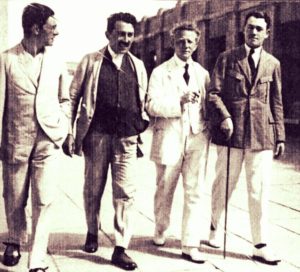

She spoke lovingly of Istvan Ipolyi, her great musical mentor. He had been a founding member of the Budapest String Quartet, an ensemble originating with Hungarians and becoming entirely Russian-Lithuanian. Ipolyi, their violist, left the group in 1927 to settle in Oslo where he formed a string quartet and taught chamber music to Gresvik.

Ipoly – second from left, with Emil Hauser, and on the right, Harry Son and Imre Pogany.

Unlike the familiar sounds of the non-Hungarian Budapest ensemble we get an idea of a far different approach from the primary group’s 1927 recording of the first movement in Beethoven’s String Quartet in F, Op. 18, No. 1:

Gresvik was horrified at the threats and deprivations the Jewish Ipolyi suffered once the Nazis invaded Norway. A biography of the quartet states: “Violist Istvan lpolyi settled in Norway, where the Budapest had spent many summers rehearsing before each concert season. During the German occupation of that country, he was arrested and placed in a detention prison, awaiting deportation to a Nazi prison. It was a nightmarish experience. “Every night, going to bed,” Ipolyi later said, “I am remembering the horrible feelings I had on the evenings in the concentration camp, never knowing what the next day will bring. Through the personal intervention of Count Bernadotte, head of the International Red Cross, lpolyi was freed. He fled to Sweden and remained there for the duration of the war. On his return to Norway, he became a Norwegian citizen, mentor of a quartet in Bergen, and a professor. He and his wife lived what he called “a rather secluded life.” He loved teaching, he wrote Sasha [Alexander Schneider), who sent him food packages after the war-“I feel drunken when working with my favourites. And particularly with the quartet.” Mischa saw to it that he received the royalties due him from record sales. Ipolyi wrote several books, claiming to Sasha that he had “found an entirely new theory of the origin of music.” He died in Bergen on January 2, 1955, at the age of sixty-eight.”

Gresvik passed away in 2000 at the age of 92 and when I located her one descendant, a daughter in Oslo, she was about to be hospitalized for intensive therapy and excused herself from being able to help find and preserve her mother’s archive. Once you hear Gresvik in 1948 playing Grieg’s Ballade, Op. 24, a variation on a folk song, you will sense how urgent it is to rescue whatever is left of her legacy and bring to light any of her radio recordings from their silent tombs.

–Allan Evans ©2016

Superior playing by Ingebjørg Gresvik! Great article… fascinating.

transcendental performance!