Fried was everywhere, at the crucial moments of music’s inner life. Dining with Ravel, Stravinsky, Nijinsky in Paris the night before he joined them for the Rite of Spring’s premiere. He was the first to conduct for the young Horowitz after he managed to get out of the Soviet Union, the first one backstage when Bartók premiered in Berlin, with Prokofiev for their last concert in Berlin soon before the Nazis took over. Lenin met his train when he came as the first foreign artist invited to the new Russia, joining a nude dance of Josephine Baker at his count friend’s Paris pad.

Fried hid his tracks with sparse yet sharp-edged interviews, probably due to side activity like the Bolshevik espionage most likely detailed in a forgotten NKVD dossier awaiting rescue after someone gets bribed in Moscow. His death was reported as if it had been a staged event: cursing the overhead German planes from a hospital death bed during the week when Stalin cleaned out all remaining Germans from the capitol, even though Fried took on Russian citizenship some years earlier. No one knows where and if he was buried. Alexander Gurdon, a German scholar, crafted a dissertation on Fried that awaits publication and translation.

As a musician, Fried grasps and projects the essence of each work he takes on. Tchaikovsky reaches us through this Nutcracker Suite’s Arabian Dance with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra. We’re hypnotically lured into a sonic tent:

While Tchaikovsky may charm, it’s Fried’s association with Mahler that draws the composer’s numerous admirers like moths to light in order to pick Fried up for a momentary glimpse based on one major piece of recorded evidence. As someone unable to endure Mahler’s undermining expressive moments with kitsch, it seems that devotees of his music abuse it as a soundtrack for onanistic reveries. As a once would-be biographer I would have been compromised by my reluctance to explore Fried’s association with the composer as it would have incurred over-exposure to his music. Fried sits on the right at the Mahler family’s summertime lunch:

Fried’s main concern to the Mahlerians was his achieving the first recording ever of a complete Mahler symphony, the Second with the Berlin Staatsoper in 1924. It is accepted as a relic of their profound relationship although all previous attempts to restore it obscured most of the details, therefore making it even more eligible for their mental vagaries and anything but a palpable musical experience. I dragged its opening through the depths of my sonic depth technology and came up with this result:

Of course even an improvement over a reduced symphony orchestra stuffed into a tiny space to pour out their soundings into a lone recording acoustical horn will also be compromised, as their need to stop every four minutes for a new wax to be loaded and record the next section limits continuity and a full capture of its timbres.

The British Library turned up a collection of UK home recordings made in the 1930s and one had been mislabelled in their catalog as conducted by Iskar Fried. It contained a movement from Das Lied von der Erde, broadcasted by the BBC in 1936 with an alto soloist pouring out its text in English. Taken from a real life event with full orchestra, captured by microphone and with a complete absence of any time constraints, we clearly hear Fried’s projection of Mahler’s orchestra. Nothing metronomic about it as the song flows before landing into an explosion. The full performance is published on our Oskar Fried CD:

but here is the opening of An die Schönheit with Astra Desmond, alto. :

Yet with all the Mahler studies, conferences, texts, media attention, this unique performance has been uniformly ignored, perhaps by its threat to the security of Mahlerian dreamers reluctant to allow any new evidence to upset the pecking order.

Fried was a witness and interpreter of Stravinsky’s new music, being a pioneer when he and the Berliners recording the Firebird Suite. Who would have had the guts to be the first German conductor invited back to Paris after World War I and offer the riot-provoking Le Sacre paired with Beethoven’s Ninth? He luckily was recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade in 1928. One’s expectation and craving intensifies with each phrase:

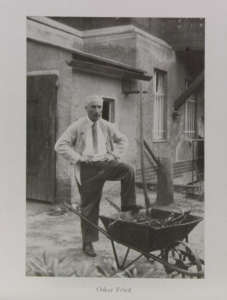

Fried lived with his dachshund in a house outside of central Berlin, aside a lake. One reporter espied him at home (left, holding an axe):

Fried often programmed Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Berlin tradition was to perform the work on New Years’ Eve in a hall and over the radio. The Berlin Philharmonic left us a version that he recorded in 1928. Hearing the entire work goes beyond merely attending a performance or playing a recording as its opening of the Scherzo illustrates:

This way of making music interrupt the mundane by opening onto a higher plane of existence distinguishes Fried as a force who offers us musical epiphanies that can only result from one who remained an individual without succumbing to musical trends and societal pressure that try pressuring the arts to “make nice.”

William Faulkner stressed the urgency in safeguarding individuality, a necessary reminder in our time of how easily it is lost through standardization and society being controlled by the media and corporations.

©Allan Evans 2016