Such a strikingly autochthonous and mysterious American Art music, allegedly risen up from unknown and lost origins, abounding in myths spouted by latter-day aficionados. For many, our earliest exposure to primal Blues came through Robert Johnson.

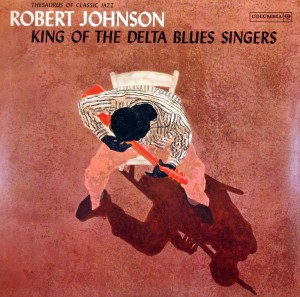

Until recently there were no images of Johnson, depicted here as a generic rural guitarist. One could only fantasize over his missing features, attire, and character. The stereotype pose foisted onto his sole record-jacket didn’t help clear the fog until a recently discovered photo reveals him to have been dapper, possessing endlessly long, slender fingers that drew out a distinct lonesome sound, moaning, harsh, a repressed violence behind virtuosity too big for a rural genre in which he seemed stuck. Had he lived longer, Johnson would have moved out of the Mississippi Delta to Chicago and plugged in but being poisoned at age 27 shifted music’s destiny. Instead he has been represented as an icon that presumably attained musical mastery overnight by having sold his soul to the devil at a cross roads, filling up on supernatural fuel and paying for it with a deadly bargain. This popular myth was the brainchild of Blues fans who failed to acknowledge or grasp how hard work, talent, and musical perception shaped his artistry. Their puerile view deforms a distinct individuality into the role of a puppet in a Faustian encounter viewed from above by gawkers at a circus side-show: although the Johnson-Devil myth mirrors their own limits, it rained gold onto tribute bands such as the Rolling Stones.

Johnson’s art developed from hanging with Son House and copying recordings by other artists. Son House takes us one step back into early Blues and the hard-core gets harder:

Son House Preaching the Blues I

I’m gonna get me a religion

I’m gonna join the Baptist church,

I’m gonna get me a religion

I’m gonna join the Baptist church,

I’m gonna be a Baptist preacher

And I sure won’t have to work.

Until these recordings were discovered by outsiders, there was a veil drawn over Afro-American society and the technology of shellac discs captured a vast window onto nascent, prevalent, and passing styles, with each protagonist projecting a staggering individuality. Son House veered between alcohol, debauched living, and serving as a preacher, mixing all into a difficult but ferociously expressive art. Johnson copied his singing and extended his playing.

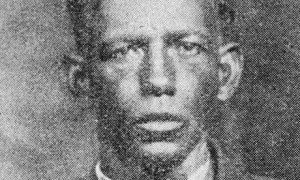

Some were untraceable figures whose entire existence remains in a few minutes of surviving sound and glimpses dwelling in testimony of older Delta denizens who stayed on or turned up in the North. Each musician enters into your hearing through their rhythm, a calling card bearing their identity. One step earlier than Son House is Charley Patton, whose wondrous gaze exists in one surviving photo:

Patton’s rhythm emerged in Son House and Johnson and sounds like their source. The poetics and narrative in Mississippi Boll Weevil were transcribed with much effort. Note how the commentator weaves a flurry of asides and observations while questioning Boll Weevil & wife with a farmer and reporting their conversation as well:

It’s a little boll weevil he’s moving it-a in the [air,] Lordy,

You can plant your cotton and you won’t get a half-a cent, Lordy.“Boll weevil, boll weevil, where’s your little home?” Lordy,

“A Louisiana raised in Texas is-a where I’s bred and born,” Lordy.Well I saw the boll weevil Lord-a circle, Lord-a in the air, Lordy.

The next time I seen him Lord he had his family there, Lordy.Boll weevil left Texas, Lord he bid me “Fare ye well,” Lordy,

Where you going now?

“I’m going down to Mississippi, going to give Louisiana hell,” Lordy.Boll weevil tell the (farmer?), “Think I treat you fair?” Lordy,

How is that, Boy?

“Suck all the blossom and leave your hedges square,” Lordy.

The next time I seen you, you [‘d]-a had your family there, Lordy.Boll weevil (and his-a) wife “We’ll sit down on the hay,” Lordy,

Boll weevil told the wife “Let’s take this forty a[cres]*,” Lordy.Boll weevil told his wife, said “I believe I may go North,” Lordy,

Lord I won’t tell nobody,

Let’s a leave-a Louisiana, raise and go to Arkansas, Lordy.Well I saw the boll weevil Lord-a circle, Lord-a in the air, Lordy.

Next time I seen him Lord he had his family there, Lordy.Boll weevil told his wife, “Lord I think I treat you fair,” Lordy,

Sucks all the blossom and leaves your hedges square, Lordy.“Boll weevil, Boll weevil, where’s your little home?” Lordy,

“Most anywhere they’re raisin’ cotton and corn,” Lordy.“Boll weevil, Boll weevil, thought I [was] treatin’ you fair,” Lordy,

The next time I (n)eed you, you had your family there, Lordy.

*This expression, like many others, had been erroneously transcribed. A new restoration I made helped me retrieve Patton’s reference to the severance pay of forty acres and a mule allotted to ex-slaves during Reconstruction, once a well-known fact but now an obscured memory.

Johnson is confined to personal anguish and busily copies other songsters’ works while House desultorily bombinates between holiness and personal abandon. Inside Patton is a vast panorama like Mark Twain’s world, narrating floods, arrests, agricultural blight, news, estranged lovers, introspection of someone’s (his?) inner life, formal presentation of religion within an entertainer’s guise and a voice unlike anyone heard since. Since drumming was prohibited under Slavery, communicating rhythms were smuggled onto the guitar and Delta musicians embodied a style deriving from African polyrhythms which their DNA reproduced, one they possessed but never directly encountered.

Patton, House, and Johnson created art music heard only in remote socially segregated roadhouses and cafes in the pre-War Delta region. One 1966 film captures a surviving Delta master, Booker T. Washington (Bukka) White placed within a recreated juke-joint ambience singing Baby, you’re killing me.

White knew Patton and House and he fleshes out our picture through another rhythmically distinct African pattern that gets his guitar into communicating a message of seduction, transmitted to a receptive curvaceous dancer who can’t resist. Son House reappears, jumping and inebriated, falling into a glimpse of his earlier life. We find them reinhabiting a lost world that gave birth to the core of Rock music, usually simplified into tributes that led the curious further to come upon America’s earliest living and documented musical treasures.