Speed breaks the sound barrier but sound breaks the time barrier. Chronology, this heap of names, dates, all pulled together in some apparent order, is intended to vaunt some sort of alleged progress. Luckily, music finally benefits from a technology that reaches into the aether to pull out living pasts from the stream of historic sound, a Heaven and Hell of sonic existences.

Whenever a composer starts creating and playing masterpieces, any imposed pecking-order within History gets irreversibly shuffled. One action mirrors others as lost arcana reappear in new, anachronistic, radical, delectable dangers that cast conventional cliche believers overboard.

Working in a quiet atmosphere at home my ongoing research is often diverted with by a force of nature sent to earth by some divinity – Romolo – whose remonstrations take precedence.

In any remaining free moments I proceed to explore composers in the act of enlivening their paper trail. The case of Béla Bartók has been in the forefront since I discovered his recordings as a pianist. Bartók is now served up as a paprika’ed Prokofiev seasoned with industrial sauce.

To hear Bartók in 1929 seated before a mic in a Budapest studio, recording his Romanian dance, a work that he experienced in situ, projects how traditional folk music unchained him from the bonds of socially acceptable musical development based primarily on the Germanic hegemony:

Almost a decade before Bartók, Sergei Rachmaninoff came into the preparation of a new century that would dissipate and destroy the last phases of his origins. Rather than wax nostalgic, he set up a style that injected elements from his past into a revamp that tended to denounce prominent melodies, flitting them into a vaporous vagary enlivened through harsh accents and lighting fast flashes in a steely color. Like Bartók’s ongoing mechanization, Rachmaninoff becomes sentimentalized by performers who wring out each and every potentially melodic gesture with utter sincerity, unaware of how Rachmaninoff’s uniqueness lay in abandoning thematic narrative. A well know Etude is played here by the composer. Melody lovers will experience unfamiliar sonic conceptions in his tone (closely imitated by Horowitz) and an approach that slights potentially lyrical lines. Most attempts to restore Rachmaninoff’s legacy end up sounding boxed into a sanitized cramped compromise. Here he is, once again, after a long time’s absence:

l. to r.: Rachmaninoff, Walt Disney (American entrepeneur), Vladimir Horowitz. [n.b. tell-tale body language]

A decade older than Rachmaninoff, Claude Debussy’s ethos surfaced by destroyed any lingering dependency on the eclipsed, passé Wagner; his approach was influenced by art and literature of the time, mores through a serendipitous exposure to Asian music and decadence. In later years Debussy metamorphosed into a different composer, one who brings stress to musicians grasping hard to surmount his change in a struggle to purvey the earlier smooth Impressionistic attire into a new craggy terrain. Debussy obliged by recording paper rolls via the inaccurate mechanical player-piano but his genuine pianism survives on four songs when he accompanied Mary Garden on an upright piano in 1903 at Paris’s branch of the Gramophone & Typewrite Co.

The lucidity and relief in Debussy’s touch casts doubts on the atmospheric Turneresque blur of the legendary Debussy specialist Walter Gieseking: nasal adenoids intruded on permitting a clearer sonic reproduction, therefore compelling his producer Walter Legge to make awkward mic adjustments decisions, creating an accepted misty mis-conception of Debussy’s music.

Debussy never set foot in Spain but a Catalonian composer born a few years before him dug deeper into outsider music. Although Debussy had limited acquaintance with Javanese music and once hosted a veena player in his home, Isaac Albeniz thrived alongside flamenco culture. Albeniz died young and obese, and any hopes to unlock his interaction with non-Germanic music and how it was absorbed into his innovative spirit seemed hopeless until the discovery that a Catalan-coast resort owner had bought Edison’s newly invented recording machine and urged Albeniz to sit before the horn. He improvised three works (in 1903) and anyone familiar with his composed pieces will hear something equal to his finest efforts. (photo with his Italian pupil Clara Sansoni, who recorded several of his works):

Before Debussy, Norway produced Edvard Grieg in 1843. His full-fledged Germanic training was successfully exploited to incorporate the folk traditions of his native realm into his creations. Grieg too sat at the same Parisian upright that Debussy played on while touring throughout Europe in 1903 and left twenty minutes of his own music. Note how Grieg’s Minuet from an early piano sonata bears a folk rhythm that is not indicated in his printed music, and how his performance bears an energy and freshness that engage him long beyond the act of creation. Grieg’s irregular rhythm incites with a clue for playing Chopin’s Mazurkas:

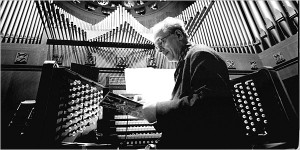

One year younger than Grieg, organist and composer Charles-Marie Widor exulted in the innovations achieved by the builder Cavaille-Coll, one that led to symphonies being composed for solo organ. Widor commanded Paris’s Ste. Sulpice and was recorded playing excerpts from his works at age 89. One movement from Widor’s Ninth Symphony shows how space influences coloring and density as the interior’s resonance flirts with his breathing mystical phrases:

As folk music and Modernism destroyed the Nineteenth Century for good, Widor and others who explored the organ gave a base to Olivier Messiaen, a spiritual seeker who employed Indian raga scales and rhythms, chant, and birdsong. His first published organ work, Celestial Banquet, was one among many recorded by him in the summer of 1956. New technology helps restore the organ’s patina that was kept dim by record labels’s industrial standards:

The past collides in the present as the present is in the past of the future so presently, Yoshi Wada performs tonight:

Inspired composers at large capture our attention:

Allan Evans ©2014

Very compelling, fantastic.