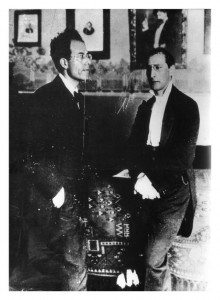

I cannot resist leaking parts from sounds too good to hide before publication and tweak your antennae. One musician-enigma is Oskar Fried, the Berlin conductor seen above who trained dogs and circus animals before arriving at the Berlin Philharmonic in 1905 without previous experience. Mahler was then on the scene as an opera conductor whose own works attracted devotees. Fried sought Mahler in his guise as director of the Vienna Philharmonic to complain about how one of his works was being mauled by another Viennese conductor. Before much else was said, Mahler informed Fried that he was a conductor, whether he knew it or not. “It’s not written on my face” Fried snapped back, to which Mahler stated, “I know my own people.” In 1924, Fried somehow crammed the Berlin State Opera Orchestra into a studio and became the first musician to record a Mahler symphony, the Second, and in its entirety, but into a horn, as the microphone was yet to arrive.

Fried became very close to Mahler (as seen in this early photo), a disciple to his prophet, and his sonics open a view onto the composer’s own art. The dreadful sounds inhabiting his restricted dim acoustic recording stirred me up to try another approach and liberate his sounds. Here is how the opening now plays:

While Mahler was brewing I revisited home recordings of Rev. Gary Davis, made in a courtyard semi-shack he inhabited stuck behind a Bronx tenement in 1951, the first tapes made of Davis, absent from the pressure of a format setting. He sings a gospel tune with his wife Annie (seen together here about fifteen years later):

An early sermon also survives, finding his thorough reading of the sacred books leading him to preach and reach great intensities that also dwelled in his singing and projection through his alter ego, the guitar:

An energy touches these musicians who vibrate as conduits for a force that projects through their singing and playing. Indian music has a sarod master, Buddhadev Das Gupta who recently appeared here in New York.

The raga Zila Kafi has a deliciously cloying melody in its final phase, capturing a sultry rapture. Das Gupta worked as an engineer and thus avoided the politics and limits of commericalized musical styles, keeping his tradition pure:

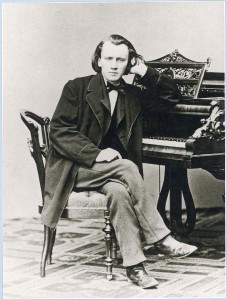

Energy caught on wax, as Brahms himself cut a cylinder for an agent of Thomas Edison’s who conducted a whirlwind blitz throughout Europe in 1889 to capture celebrities’ voices.

Luckily Brahms did more than just announce his name as he left behind two excerpts, one well known (for being inaudible) Hungarian Dance of his own and a second work: you’ll be rewarded after enduring the first seconds of harsh noise with Josef Strauss’ Die Libelle.Polka-Mazur fur das Piano Forte,op.204. I heard it in Vienna in 1984 and was dismayed at how inaudible it was, taking their word that the buried pianist was the composer himself. As the recording surfaced on the internet, it was time to probe and here we are.

Soak up his own touch, his insistent Harlem-like rhythm and encounter a vivid slice of time projecting his life while he was alive and reactive with a playing that escapes living-room niceties by offering vision and style.

Plan on hearing this fragment return in new clothing as experiments continue to appear on these pages. . .

©Allan Evans 2012