When a cello plays you expect its low range to provide a buttress that stabilizes its highest singing registers that copy operatic and lieder singing. Before the mid-19th century cello works were infrequently composed, apart from Beethoven’s five sonatas, one by Chopin, as most composers shied away due to the difficulty in balancing it against other instruments that would invade and obliterate its tessitura. Bach alone fathomed its depths. He also wrote for viola da gamba (leg viola) but ventured far with an unaccompanied instrument to offer dance rhythms and polyphony. One wonders if he was aware of Marin de Marais. . .

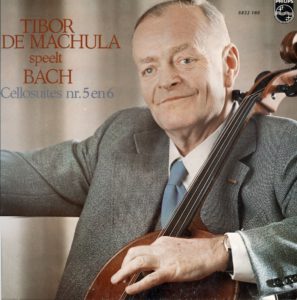

Tibor de Machula (1912-1982) playing Bach came as a jolt. So many violinists have Hungarian pedigrees, as did a smattering of cellists who were of lesser interest to the music scene due to their smaller repertoire but de Machula’s approach has reshuffled the pecking order. Cello playing flourished mostly by apeing violin and vocal styles, something that negates any hidden and unique properties in its ties to earlier and distant instruments. All the mannerisms and limitations that burden older styles,the sliding, egomaniacal display, publicly airing one’s nervous system, or regression into gelid remoteness like Heifetz’s, is now becoming a freeze-dried abstraction lacking healthier origins. The riddle of what lies within a cello comes through an instrument that spanned the Silk Route and was adapted into European versions: the morin huur, a two-stringed horse-headed Mongolian fiddle.

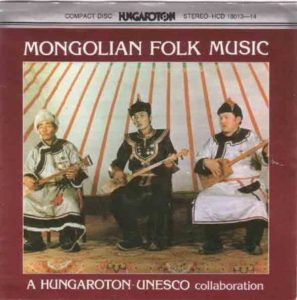

Although Hungary was repressed under Russian domination, one escape route came by their extensive UNESCO funded research into salvaging and publishing traditional music and uncovering their own origins beyond Transylvania. One team entered Mongolia in 1967 when it was closed to many non Soviet-bloc countries.

The Hungarian team located Dorzhdagva, a master of whom photos have yet to surface, who plays and sings to epically recount his instrument’s origins, imitating a horse’s sway and rhythm:

His fiddle richly emanates overtones, an integral part of their throat singing, with possible origins in Buddhist chant that inevitably grasps harmonics, prominent in Tibetan and Japanese monastic orders.

Csangos, the Hungarian settlers who remain on the far-eastern extremity of their European settlements transform a cello into a percussion instrument that they call the gardon, imitating the morin huur’s trot.

As Hungarians continue to name boys Attila, one wondered if something inaccessible or lost remained when playing classical music on the cello. De Machula had an early debut in Budapest and was welcomed at the Curtis Institute of Music in 1927 (age 15) where he studied cello with Felix Salmond for three years. Soon after returning to Europe he became principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic in 1936 (age 24), remaining there until he was offered to lead the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam in 1947. Aside from too few studio recordings, live performances were limited by his orchestra’s schedule and it is rare to hear him in action. De Machula’s daughter Barbara created a documentary film on her father (http://www.tibordemachula.com).

Barbara de Machula generously provides us with Bach’s Cello Suite in D major from a 1976 recital. We hear part of its opening Prelude:

I was stunned not only by de Machula’s playful polyphony, his courage to project low tones that are usually restrained under the sonic carpet, but a sound evoking the morin huur itself, one that arrived when Mongolians and nearby groups migrated West to the Danube. The lowest string envelops the music with an aura of overtones to project a colorful and captivating Bach. Like the Hungarian pianist Irén Marik, de Machula displays a uniqueness in Hungarian master musicians who grasp a work’s entirety, instantaneously, and then labors to have the body realize what they have intuited. De Machula’s bowing channels the morin hour’s soul with a rhythmic life of its own that creates a synthesis of instructed, genetic, and personal elements. The cello seemingly plays itself

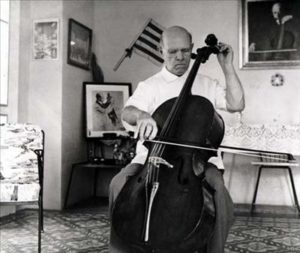

There were fewer active instrumentalists when Pablo Casals (1876-1973) picked up his cello. They tended to accept predominant violin styles as a guiding model for approaching other string instruments.

Casals emerged from a narrow void to forge his own cello practice. He seemed reluctant to allow elements of traditional music to overlap with Bach, whereas flamenco and cante jondo were seized by Albeniz, Falla, and Debussy for their compositions. His cello viscerally rang out, expressing himself and his instrument in a Schumannesque-Brahmsian manner. A 1930s performance of the same Prelude is played by Casals:

Jack Bruce (1943-2014), a classically trained cellist, composer, bass player, and singer shared his love for an instrument that dominated before life made him into a rock star.

Arbiter is preparing to release performances by de Machula and his teacher Salmond that will bring to light their eclipsed traditions.

One explorer of Central Europe and Mongolia is the Berlin-based American composer Arnold Dreyblatt (http://dreyblatt.net), who absorbed Csangos and Mongolian idioms to create a musical language that expands into text and installations. Instruments have are excited, rewired to create layered overtones and circulate in a flurry above solid grounded pitches that release them.

These sublime roots continue to inspire a composer’s investigative wanderings.

https://vimeo.com/arnolddreyblatt

Allan Evans ©2016

de Machula and Salmond… two wonderful, suave, open-hearted players who get it right. Can’t wait!!

According to Menuhin, Casals Often emphasized the “gipsyness” in Bach

Please let us know when you are releasing recording of de Machula and Salmond: email address below.

My late father-in-law, Benjamin Grobani, studied voice at Curtis and toured Europe with de Machula. I have several posters oftheir concerts in various European cities.