Debussy’s Canope seems to clash with the other occupants inside his second book of Prèludes, or to obtrude among anything else he composed. Most pianists treat it as a solemn funereal dirge with some peculiar notes, making it in to a string of moments meant for obligatory contemplation of something deep that eludes them and the performer as well by sounding disjointed. A matter of restraint, as if attending a lethally slow religious rite carried out in an unknown language, puzzled by watching others respectfully accept it as a spiritual offering.

On a journey to Cairo I spent time with Hassan Aziz Hassan, a pianist who was close to Ignace Tiegerman, Chopin’s reincarnation on the Nile, and spent time painting when the relatives whom he took in after the 1952 coup weren’t being too aggressive with him. Before leaving Egypt I asked if he would guide me through the Old City, temptingly placed above a distant hill. We set off, Hassan in sunglasses (facing camera) along with the Paris-based Cairene pianist Henri Barda (left).

To my eyes, trying to unscramble the abstract chaos of Mamluk architecture rampant in the old quarter was awkward.

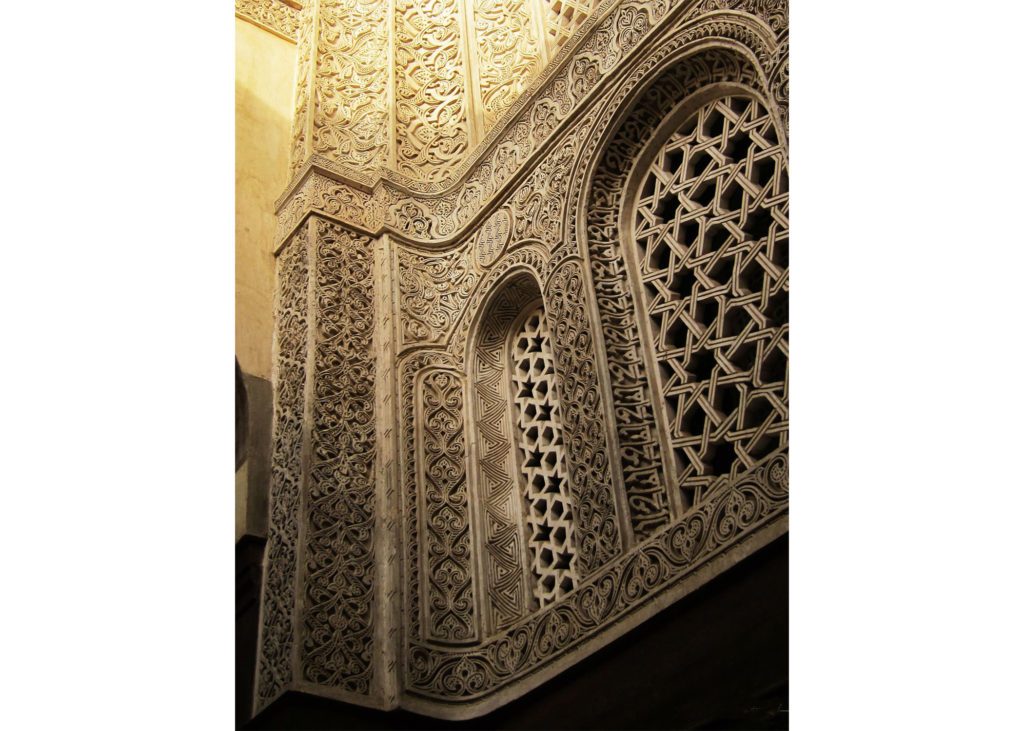

Dizzying details of Qalalun’s mithrab added to disorientational delight:

Hassan blithely put my confusion to rest by indicating how certain patterns spilled into arcs and replicated like ripples over non-figurative surfaces. He was eager for an upcoming publication of his family memoir being published by the American University of Cairo Press, as he was a prince, first cousin of Farouk, the last King of Egypt. His Cairo had people like Edward Said playing tennis and also studying piano with Tiegerman, their local musical divinity. Hassan recalled: “Before the Revolution [in 1952] everyone toured here: Furtwängler with the Berlin Philharmonic, Bachauer, Kempff, we heard everyone, but Tiegerman was superior.”

While the family was of Albanian origins, Hassan’s mother was from Spain and was kept distant from her son for not having been brought up in a palace. Her absence haunted him throughout his life. There were many friends and one could arrange masquerade parties such as this one from the late 1940s where Hassan is second from left with his sister Princess Soraya far right, seated, with her hand clasped by Nahum Jojo, son of Cairo’s chief Rabbi, kneeling at her feet.

On the day of Hassan’s book launch party, news came that he had passed away in the morning.

Others like Hassan appear to open up the architecture, even within sound, as we now turn our attention to and overlooked American pianist whose wealthy Bostonian father had wed a woman from Spain: George Copeland (1882-1971):

Copeland had a few piano teachers in his youth and lived for awhile in Spain but seems to have been so perceptive that life and experiences alone sufficed to sharpen his music more than formal lessons. After many years in Spain he eventually settled in New York. During a 1911 European tour, Copeland was in Paris and left a lengthy memoir about meeting Debussy:

Punctually at eleven, we were shown into M. Debussy’s salon. The room itself constituted my first surprise. It was very long, very formal, and very well kept, whereas I had expected to find myself in an entirely bohemian menage. A moment later the door opened and I received a second shock.

As I have said before, I had entertained a preconceived notion of my host as being thin, nervous, effete, with the unhealthy look of the habitué of Paris night spots – and, most certainly, untidy and careless in matters of dress; in short, a typical denizen of Montmartre. To my amazement, I found myself rising to face a tall, dark, heavily built man, impeccably dressed, who gave the impression of relaxed, almost feline strength, and who had the most penetrating black eyes I have ever encountered – like two pieces of shiny black jet. Señora d’Alvarez [possibly Marguerita “Nina” d’Alvarez, singer] made the introductions: “This, M. Debussy, is M. George Copeland, the pianist, who has introduced your beautiful music to America.” ”Vraiment!” was the laconic reply, and with a brief glance in my direction M. Debussy crossed the long length of the room and seated himself on a stiff green sofa at the far end. Apparently he was as undesirous of meeting me as I had been of meeting him; and although he must have been aware of the fact through J. Durand, his publisher, he appeared completely indifferent as to whether his music was played in America or not.

As conversation at that distance was impossible, I suggested to Señora d’ Alvarez that perhaps we should leave. “Nonsense!” she retorted. “You must play for him.”

“But he hasn’t asked me to play,” I replied angrily. “Perhaps he doesn’t even wish to hear me.”

“Of course he does! Go and ask him,” Nina replied in an impatient whisper.

So I rose and, feeling as awkward as any schoolboy, crossed to where he was sitting bolt upright on the sofa. “Would you like me to play for you, M. Debussy?” I asked cautiously.

The composer eyed me calmly. “Mais oui,” he replied. I waited, but there was no further comment.

“Shall I play you some Spanish music?” I asked, as this was one or the things I specialized in.

“Spanish music!” he exclaimed in surprise. “Mais non! Why should you play me Spanish music! It does not interest me at all.” Then, lowering his voice, as if thinking aloud, he continued: “No, the only music that interests me is Bach’s and my own. Après tout, Bach has said all that there is to say in music – the rest of us only say it in different forms!”

The piano, at the far end of the room, was draped with a silk scarf held in place by a heavy cloisonné vase. I asked permission to movc the vase, so that I might open the piano cover.

“Absolument non!” he replied with obvious annoyance. “Do not touch it! I never permit that anyone should open my piano. As it is, everyone plays my music too loud.” Sensing the futility of argument, I seated myself and played through the shorter piano music – Reflets dans l’eau, La cathédrale engloutie, Suite bergamasque, L’isle joyeuse, Pagodes, Hommage à Rameau, ‘Poissons d’or, Voiles, the Danse de Puck.

M. Debussy had risen shortly after I began playing, and had seated himself close to the piano. When I came to the closing bars of Reflets dans l’eau,he got up from his chair in apparent excitement and, pointing a long finger, exclaimed: “Why did you play the last two bars as you did?”

“I don’t know –” I was puzzled. “Perhaps because that is the way I feel them.” “It’s funny,” he said reflectively, “that’s not the way I feel them.” But when I said, “Then I will interpret them as you intended,” his reply was a definite “No, no! Go on playing them just as you do.” He made no further comment until I had finished and had risen from the piano. Then, with an audible sigh, he said simply, “I never pay compliments. I can only say that I have never dreamed that I would hear my music played like that in my lifetime.” In that brief moment, our relationship had undergone a sharp metamorphosis. Señora d’Alvarez and I left almost immediately, but as I took my leave M. Debussy asked me to come again at eleven the following morning. In a daze I consented, and on reaching my hotel I immediately called the steamship line and cancelled my passage.

I remained in Paris, in close daily association with Claude Debussy, for the next four months.

Every morning I would arrive at the same hour, and we would spend the day together in almost elemental companionship, reading, or playing music – sometimes not exchanging a single word throughout an entire morning. If, in his reading, Debussy happened upon something provocative, or something which he thought would interest me, he would rise from his chair and point to it in silence. It was his belief that conversation was unnecessary unless there was something essential that one wanted to say. I did not miss the conventional chatter.

One of the basic factors in Claude Debussy’s genius was, I think, his ability to eliminate the obvious, the unnecessary, and the trivial, and in this way to conserve much vitality. He was in no wise a misanthrope, for he was deeply attached to his friends, but he was not al all interested in the nature of man. He believed that only a few arrive at any sort of maturity, and he avoided the fool and the common-place. He achieved in his music (with only a few exceptions) an almost complete elimination of personal equations, regarding himself (the musician) as a species of sounding board held up to nature. To this end, he had to keep himself free from interference; and he indubitably heard sounds that other people have never heard.

Debussy’s study was an extremely simple room, containing one or two good pictures and those jade animals and pieces of Chinese pottery that were, apparently, his one personal extravagance, and about the acquisition of which his biographers have told many tales, real or invented. The room had a Pleyel upright piano , at which he worked on manuscripts which he was composing , as well as on those which required further polishing .

I spoke to him of my desire to transcribe some of his orchestral things for the piano – music which I felt to be essentially pianistic. He was at first sceptical, but finally he agreed, and was in complete accord with the result. He was particularly delighted with my piano version of L’ après-midi d’un faune, agreeing with me that in the orchestral rendering , which called for different instruments, the continuity of the procession of episodes was disturbed . This has always seemed to me the loveliest, the most remote and essentially Debussyan, of all his music, possessing, as it does, a terrible antiquity, translating into sound a voluptuous sense that is in no wise physical.

Claude Debussy would, not infrequently, inject in to some current discussion his reaction to, or estimation of, other composers. Among his contemporaries, he was most fond of d’Indy, Chausson and Ravel, although he thought the last of these too lush in his orchestrations. He admired César Franck greatly, describing him affectionately as “a man without guile, and full of trustful candour”. Whatever Franck “borrowed from Life”, said Debussy, “he restored to Art with modesty verging on self-effacement.”

Debussy spoke of [Alessandro] Scarlatti as an “inexcusably forgotten composer”, whose Passion of St. John he described as “a little chef-d ‘oeuvre of primitive refinement and beauty, in which the style of the choral music is seemingly of pale gold, like those lovely backgrounds to the profiles of the Virgins in the frescoes o f his period”.

On the other hand, he ridiculed Grieg, whose music he described as “a pink bon-bon stuffed with snow”; and of Saint-Saëns he exclaimed: “I have a horror of sentimentality, and I cannot forget that its name is Saint-Saëns!”

Debussy liked Mozart, and he believed that Beethoven had terrifically profound things to say, but that he did not know how to say them, because he was imprisoned in a web of incessant restatement and of German aggressiveness.

He came to hate Wagner as much as he had first admired him, describing his music as “strange, beautiful, seductive, and impure” – remarking of a performance of Das Rheingold, “It took two hours, and one hesitated between a desire to go away and the desire to go to sleep!” Debussy himself wished to write an opera on the theme of Tristan and Isolde, which would be in exact style variance with the Wagnerian version. How much of this he completed, we do not as yet know.

Perhaps the composer whom he most admired, and upon whom, if at all, he most consciously patterned his music, was Rameau, whose genius, compounded of delicacy, charm, and restraint, he regarded as being in the true French tradition. It is probable that Rameau opened for him, if only a crack, the door which led to that other-dimensional music of which Claude Debussy became the high priest, and which he discovered and explored so extensively.

Musically, Debussy felt himself to be a kind of auditory ‘sensitive’. He not only heard sounds that no other ear was able to register, but he found a way of expressing things that are not customarily said. He had an almost fanatical conviction that a musical score does not begin with the composer, but that it emerges out of space, through centuries of time, passes before him, and goes on, fading into the distance (as it came) with no sense of finality.

When I asked him why so few people were able to play his music, Debussy replied, after some reflection: “I think it is because they try to impose themselves upon the music. It is necessary to abandon yourself completely, and let the music do as it will with you – to be a vessel through which it passes.”

George Copeland

Debussy, the man I knew.The Atlantic Monthly. January 1955.

At the last piano recital Copeland gave, in May of 1964 at age 82, he played Debussy’s Canope. Until this performance surfaced, the ballpark average tine to deliver this Prelude weighed in at 2:30 with some bordering on 4:00. The first to record it was the Lyon-born Walter Gieseking whose lengthy London sessions after the Second World War had impressionistic microphone placement as the pianist sometimes snorted and this more-than scuro obfuscated any chiaro. Having a producer like Walter Legge allowed the company to squeeze three projects out of him in the time that would yield one for other pianists.

Please rise as we will now hear Herr Gieseking intone the Canope:

Score: WG 2:39/CD 0:00.

Please be seated. His playing lived in the moment, following into the next, anyone still awake?, and had flourishes as well. If its seriousness is not fully appreciated, if it is not a masterpiece but seems dull and desultory, whom shall be blame? Ourselves, for not having undergone rapt attention, the Pianist, for doing all in his power to save a failed piece, or the Composer, who should have had second thoughts about its very birth?

In the steps of Prince Hassan, Copeland steps in to offer an awareness of structure that only materializes when the piece is played at a faster pace. From his last recital:

Score: GC 1:47/ CD 1:47!

At this speed arches appear, reappear, stray notes exist as details within larger gestures, firmly coherent and conceived. Copeland may be the first to bring light to this overlooked treacherous trap that is continually slain through the best of intentions that wish to treat it as a sacred soundtrack to contemplate jars containing organs of the dead. And let’s hear Copeland regail the curious at a pre-concert talk. Much of what he says is in the Debussy memoir seen above. As he was not sitting near a mic one will need to listen carefully (another first publication, folks!):

That same day, Copeland played Debussy’s Engulfed Cathedral in a way that corresponds to how Debussy played an enigmatic time change after the opening statement:

Another popular Prelude, La Puerta del Vino, sails into the harbor with a habanera beat. This may inspire many to languor in the wine, basking in sunshine, blue skies and head into a Renoiresque putridity. Copeland prefaces his dive into the lower depths with a warning that this upcoming port was rife with murders, suicides, underworld, pirates, a murky, shadowy, evil place:

Our ongoing exploration of Debussy continues! Although 2018 was the centenary of his death and is now so oh-so yesteryear, we’ll continue to keep him alive and smoldering!

–Allan Evans ©2019

Wow!!! Great memoir, great comparison of Canope. Keep this stuff coming!!

During Copeland’s Q&A to the Yalies, he mentions that when he invited Debussy to a performance of Pelleas & Melisande. Debussy refused: “They sing it the way everyone else sings.” Some time later, Debussy asked Copeland to join him for Puccini’s Tosca. Copeland mentioned “But you said you dislike Puccini.” Debussy answered :”They sing it like my music!”

Copeland does open our eyes and truly provides new perspectives which are really old! Funny what is lost in time.

Dear Mr.Evans, here I sit in a night freshing as the moon shines on the temple that was, remembering your greatness in contributing for the good music. RIP.