We’ve been engaged in searching within Russia’s soul and how its classical music grew from a mere dozen into a global phenomenon. Just a miniscule teacher-pupil chain led from the local works of Glinka into the far-fetched paths of Prokofiev, Stravinsky, and Scriabin, the development of conservatories, professional orchestras that wield an influence felt everywhere. All in a half-century of feverish fervor. Their music divided early into a faction seeking to rival the West and take up its theory while another shunned foreign influences to delve into Pagan rites, folk music, fairy tales, the occult, mythic dreams, and explore the unfathomable East.

This give and take was not lost on Ravel and we will close in on a Menuet included in the Tombeau de Couperin to encounter varied approaches. First comes the highly-touted style of Walter Gieseking,

a player upheld as an exemplary master of works by Ravel and Debussy.

The record company’s London producer kept the mic at an Impressionistic distance to muffle snorting caused by the pianist’s nasal polyps, dragging the vinyl’s listeners into a Turneresque landscape.

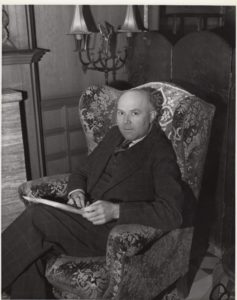

Next is Marcelle Meyer, who also recorded Ravel’s complete solo piano works. Meyer was very tight with Jean Cocteau and a literary elite, seen here with the poet Raymond Radiguet who died at age twenty-three.

Her performance dates from the time of Gieseking’s:

Madeleine de Valmalète cut her first shellacs in a Berlin studio in 1928, her twenty-ninth year. De Valmalète lived a week beyond her 100th birthday, which she celebrated walking to chat and embrace each and every guest. She was the second woman in France to obtain a driver’s license and the first pianist to record the cycle. (photo at her centennial celebration:)

Her Tombeau is published on Arbiter CD 144:

From Cairo comes Henri Barda, whose family hastily left Egypt during Nasser’s revolution. Settling in Paris he studied with Lazare-Levy after having had lessons with Ignace Tiegerman.

The complete Tombeau from a 2012 concert is on YouTube and within the cavernous hall we experience his Menuet:

For those of you who have troubled to hear all four, we now close in on to the middle section’s climax, a dream within a dream that dissolves into the opening’s return. Here are all four playing this excerpt and note how some will give emphasis to the right hand whereas others show how the left hand creates a rough awakening that bears lingering shards of the oneiric journey, followed by a slower tempo, as if one has need for a moment of regaining consciousness. I leave it to your ears to observe who is doing what and would welcome any comments. . .

Gieseking:

Meyer:

de Valmalète:

Barda:

©Allan Evans 2016

Interesting. I am not fond of any of these actually, all for different reasons. Gieseking is too slow; I don’t like the way Mayer breaks the hands- it sounds mannered. De Valmalete is probably the best, nice tempo, and on second listening I like it. The Barda is an awful recording so I can’t tell much, but it definitely loses the minuet feel, which I like to hear. Fun to listen to!