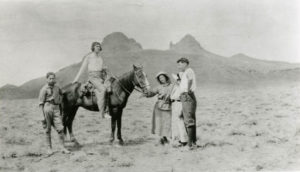

Cheyenne warrior

Before arrivals came from all corners of the earth, our Native Americans had ongoing traditions that others were – and still are – unaware of. One of the first to explore their culture was Natalie Curtis Burlin (1875-1921),

a pioneering musicologist who went West in her twenty-eighth year to record and document the singing and ceremonies of our primary residents. Her astonishing work is preserved on a website.

While Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

was based in New York, he often met with Curtis. According to her website,

The Indian themes Curtis published caught the attention of other musicians and composers interested in folk music, including Percy Grainger, Kurt Schindler, and Ferruccio Busoni. Grainger and Curtis became good friends, and Grainger continued to use Curtis’s arrangements in his concerts and lectures throughout his career. In Europe as a teenager, Curtis had studied briefly with Busoni, and he had continued to follow her work. In 1911, Busoni asked Curtis to send him a selection of Indian melodies that might serve as suitable themes for an experimental composition. He used the melodies she sent as themes for his Indian Fantasy [and Indian Diary for solo piano].

A Cheyenne war song from her book on American Indian music was used by Busoni as his Indian Diary’s second piece, performed by his pupil Edward Weiss (1892-1984) in 1952:

Busoni channeled the outlines of the rhythms and war cries into a modernist setting, an example that paralleled the way Bartók was then expanding his musical language. Note at 0:57 – 1:02 how Busoni quotes a phrase from his own Piano Concerto, a surrogate self-insertion into the narrative.

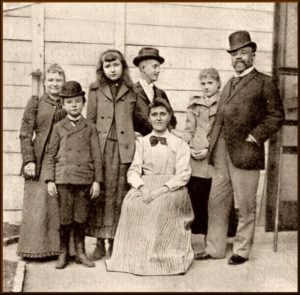

Another European who temporarily resided in the United States was the composer Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904).

His patron Brahms had offered to will him his life savings if he and his family would relocate to Vienna from Prague but the Czech composer turned down Brahms’s offer for lifetime support, preferring his homeland and not to exist in the Austro-Hungarian capitol as a second-class citizen. Such a sensitivity occurred on a daily basis as his people were under German-speaking rulers and when he discovered music of the African-Americans, it transformed his music. Informing Brahms of his composing a symphony using themes from their Spirituals, Brahms implored him to send the music his way to be proofread by himself and offered to a better publisher. Dvořák’s presence in the United States as a teacher led to his advising budding African-American composers such as Will Marion Cook, the future mentor of Duke Ellington. Right after hearing this new music, he spoke to a reporter: In the Negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music.

When the Kneisel String Quartet premiered Dvořák’s American Quartet at Carnegie Hall in 1894, it deeply influenced a young African-Canadian composition student Nathaniel Dett (1882-1943)

who followed Dvořák’s developing his art through African-Americans’ sacred music. As a university-trained composer he used European practices such as modulations and structures to infuse his rhythmic syncopations. Jett’s Juba Dance was seized by the Australian Percy Grainger, who fortunately recorded it in 1922, heard here in a new restoration that extinguishes the notion that pre mic recordings (into horns) mask colors and details. It mirrors developments in the emerging Jazz genre and opened a path that led Dett to compose an oratorio for soloists, chorus, and orchestra, a bridge covering disparate realms.

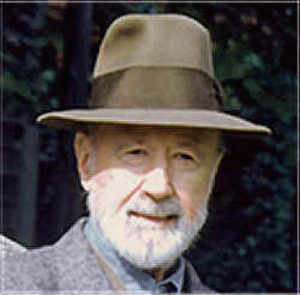

Percy Grainger (1882-1961) learned to speak Norwegian and Danish while collecting folk music in Scandinavia and was an early exponent of mixing Nordic and Asian music into an otherwise restrictive Classical sphere. Their examples were noted by Henry Cowell (1897-1965),

a composer who grew up in a San Francisco replete with friends of Chinese, Irish, and Italian backgrounds, sharing their traditional music from such an early age that it became his as well. His astute observation on the pitfalls of co-opting traditions into a more palatable and commercial venture initiate a well-defined 1946 essay co-authored with his wife Sidney Robertson Cowell on the use of folk music.

How WILL vou TAKE your folk music: longhair, Broadway or straight? The first two are easy to find on records, and the last, the real mountain music, was fairly well represented during the days when the talking-machine companies wanted to build up their market in rural America. But such music is the rarest of colllectors’ items today. For a good many years the record companies have been playing it safe, assuming that city people are too frail to stand the shock of hearing the real thing in the old mountain style. So we have been carefully spoon-fed on diluted versions, mixed with as many elements of familiar popular or symphonic music as possible, so that folk music won’t prove too hard on our nerves. It is hard for those of us who are familiar with American music outside of the big cities to understand why such careful translation into urbanese has so long been considered necessary. The wonderful things in the old Bluebird and Brunswick catalogs, for example have all been allowed to go out of pririt. Yet the few that turned up in the drives to gather old records during the war were grabbed instantly by city collectors, and dealers’ lives were made miserable by demands for more of them. The result is that today you can get Roy Harris’ “Folksong Symphony” and Aaron Copland’s “Lincoln Portrait,” both of which use American tunes in serious symphonic composition, without any pretense that the result has anything to do with folk tradition, except rather indirectly and incidentally. You can also get a lot of pieces which use titles implying some connection with folk music, although that connection is usually so remote as to be more hopeful than real.

Cowell later noted that whenever sagging, tedium, or saturation started to impede innovation in Classical music, traditional music came to the rescue, as seen in Brahms’s attraction to Hungarian and Czech music, Debussy and Ravel’s being enamored with primal Russian elements and the Javanese gamelan, and how Bartók found himself by in situ contact with remote musics in Transylvania and North Africa, a search that led him to a far greater destiny than the lesser life of enduring the limits of a pianist’s career on his composing, as he placed second to Wilhelm Backhaus in the Anton Rubinstein competition held in Paris, 1905.

Meanwhile back in America, an insurance executive was quietly experimenting with dissonance before it gradually became tolerated on the music scene. Charles Ives (1874-1954)

had the good fortune to belong to a time when small towns had marching bands that blared out popular rhythms and melodies, and an unanticipated concurrence of two oncoming ensembles playing diverse pieces delighted his curiosity and fathered his explorations. Composers often convey the excitement of their creations when recordings exist of their own performances, such as Ives playing and singing his patriotic They Are There:

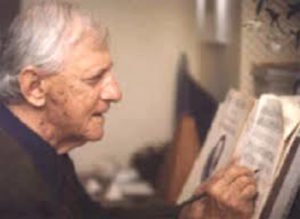

Another example is the performance of a forgotten work by the Russian-born American composer Leo Ornstein (1895-2002)

who took themes and rhythms from Tatars dwelling relatively undisturbed in pre-Soviet Russia. A piece derived from this contact was lost. In the words of his son Severo:

”

This piece was written sometime during the 1920s or 1930s but was never published. Sometime in the late 1940s Ornstein received a request for a copy, but he was unable to locate the manuscript. Recalling that he had taught the piece to a former student, Andrew Imbrie, he wrote asking Imbrie for a copy. But Imbrie was likewise unable to find the score so instead he made and sent Ornstein a tape recording of the piece. Ornstein then made an abortive effort to remember the piece, but quickly gave it up. What is presented here is the recording Imbrie made, followed by a snatch of the brief effort Ornstein made to recall it.

Force and impulsion explode in the composer’s own struggle to resurrect it, a reminder of the way of the frenzy experienced by the creator is usually reduced in the hands of others.

At a New York party around 1930, the upcoming Canadian virtuoso pianist and composer Colin McPhee (1900-1964)

heard 78rpm shellacs recorded some two years earlier in Bali that were brought back by anthropologists. McPhee’s reaction was such that he decided to abandon Western music at that moment and soon moved with his philanthropic wife Jane Below to the isle, living there for many years, documenting the music. Here is one of the discs that inspired him to exit from the West, retrieved from a collection that contains McPhee’s own discs, some of which exist in one known exemplar, saving lost music that had been out of reach to the Balinese themselves and the rest of the planet, the case of a world music trek that led to an unforseen and fortuitous repatriation.

Bali 1928 – Volume III: Lotring and the Sources of Gamelan Tradition

When hostilities in the air, McPhee returned to New York with music he had transcribed from the gender wayang, their shadow puppet theater genre, published as Balinese Ceremonial Music for Two Pianos. His colleague Benjamin Britten was in the States and the two headed into a studio to record Gambangan.

And with Asian music being played on Western instruments with equal temperament tuning came Minimalism, a dreadful label meant to cover vastly differing music that uses evolving repetitive patterns. It fortunately helped bury the rotting academic dissonant style of overly structured music so much better seen than heard, considered an intellectual highbrow experience, by injecting new life into the culture’s bloodstream. It even meant that the piano would be replaced, by electricity, and sonically sculpted. One of America’s greatest composers, Pauline Oliveros (1932-2016), began her musical life by wearing a cowboy hat and playing in accordion bands at Texas rodeos. Her interest in electronics opened a path of innovation and lifelong discoveries.

Until now, America’s newness as a continent, its unique mix of people from all over the planet, made it a hotbed for the musical and cultural innovation that occurs when contact is made between forces meeting for the first time and blending their experience without the pressure of the commercialization that Busoni despised. May their works continue!

©Allan Evans ©2017

Note: in the event that any photos contained in the post require permission we urge their representatives to contact us at once.

.

.