Other than some snoring, what was going on inside Debussy’s head? At a certain point, change was in the works, a foray into creating something that defied labels he loathed, such as Impressionist. Earlier blog posts examined how Russian music acted on his art but there are unsettling elements in his Etudes, works that Pierre Boulez described as having “burned the mist off Debussy,” not that he felt obligated to destroy any lingering Turneresque quality that many interpreters still desperately seek to impose on his last piano cycle and fail by doing so.

As an example of his new language, the Belgian pianist Marcelle Mercenier (1920-1996: alas no photos of her so far . . .) plays Debussy’s Etude in Fourths in 6’25”:

Many listeners were influenced by critics and authoritative experts that

Walter Gieseking (1895-1956) was the quintessential acme excelsior of Debussy interpreters. Nasal adenoids introduced heavy breathing while the German pianist played so his clever EMI producer Walter Legge had the recording mic impressively placed at an impressionistic distance to camouflage his snorting. The pianist rarely performed Debussy’s Etudes and his rapid traversal clocks in at 4’10”:

Mercenier played works by Messiaen and Boulez: she understood how Debussy’s last piano pieces paved the way into a new language.

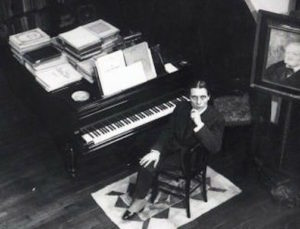

Alfred Cortot (1877-1962) was another highly regarded Debussy specialist. Among his multifold activities, Cortot managed to write a volume on the composer’s piano music, drawing on picturesque references and occasionally judging the worthiness of his works (photo of the artist at home near his beloved Renoir portrait of Wagner):

“In 1910 appeared a waltz, ‘La plus que lent,’ half a parody, half serious, and beyond question [italics mine] totally insignificant.”

Debussy’s piano roll in no way captured anything remotely resembling his touch and tone but is the Satiesque presence of a ‘ninth’ struck by his left hand’s thumb when the theme gets its final restatement, compositionally insignificant? An earlier experiment lies in Masques, an independent work from 1904. Cortot’s many students cherished the descriptions he offered as a key to each musical work played in his presence, as if he had formulated the most effective description of a work’s mood, background and expression and drew out of it like a catalog. While it could enhance a budding pianist’s grasp that something lurked behind the notes it probably inhibited them from seeking this remote sphere on their own, as his stereotypes were so seductive! (photo: joyous dining with Margarete (Mrs. Albert) Speer at the Hotel Ritz, Paris 1941)

According to Cortot’s meditation on Masques:

Without doubt there lives and moves in “Masques” all the comedy of ltaly, its color and movement: Scaramouche with his fine doings, Cassandra ridiculed, Zerbinette irritating, Pierrot dreaming to the moon and hidden by friendly night, Harlequin at the feet of Colombine. And “l’Isle Joyeuse” spreads the snare of its laughter and easy pleasures before the careless lovers whose light barks draw up on its fortunate shores, under the friendly looks of Watteau, of Verlaine and of Chabrier of whom one must think under the sensual bent of this music. Further, what we may call the pianistic orchestration of these compositions – in the absence of terms which might define more exactly the variety of combination of registers which animate them with their caressing fancy – is literally an enchantment and Debussy has never surpassed the ease and assrance with which he makes the rhythms play with them.

In spite of this, in spite of the flare and ingenuity of these two pieces, their musical attraction and the perfection of their construction, it may be we do not find in them, at least to the extent of our expectation, that rare pleasure whose secret Debussy has taught us, because the subjects he has proposed have sinned by too direct suggestion.

If one listens to the contrast between his Boulezian “mist”, whole-tone scales and Asian modes, one is convinced by the playing of Marius-François Gaillard (1900-1973) published by Arbiter in Debussy’s Traces:

that different masks are imposed by Debussy onto himself as he struggles over which direction to follow: abandoning 19th century music? whole tones? the deep influence of Javanese gamelan? Gaillard shows how the latter as having been a difficult but compelling choice.

Roger Nichols writes “Masques was published in the autumn of 1904, but has never enjoyed the popularity of its companion (L’Isle joyeuse.) True, it doesn’t have the advantage of a big tune, but the many subtleties in it should be enough to keep the most alert listener engaged. Matters may not be helped by the fact that Debussy never spoke about its meaning to anybody—all we have is a note found among his papers after his death by his widow: ‘It is not the comédie italienne, but the tragic expression of existence.’

Au revoir Walter! Au revoir Alfred & Renoir! Let Debussy rest.

©2019 Allan Evans