” Musically, Debussy felt himself to be a kind of auditory ‘sensitive’. He not only heard sounds that no other ear was able to register, but he found a way of expressing things that are not customarily said. He had an almost fanatical conviction that a musical score does not begin with the composer, but that it emerges out of space, through centuries of time, passes before him, and goes on, fading into the distance (as it came) with no sense of finality.” – George Copeland

Like so many other composers who create new sounds and pieces that form themselves, entropy sets in to control their creations’ legacies. From the initial shock comes a scramble to idolize, protect, followed by deconstruction and then a generation or two on, wondering how it all began.

Debussy, a victim of such incomprehension even during his lifetime, has been dragged into an inoffensive respectability that he loathed. Once at the home of a distinguished, refined, cultural socialite, we learn from Percy Grainger how he “met there Grieg and [Richard] Strauss and Debussy at the Speyers, And Debussy was like a little spitting wild animal. Lady Speyer invited some friends to tea and he said “Tea! I won’t be in the same room with anybody. Bring me in my tea here, where I can drink it alone.”

Can this be the delicate composer referred to during a master class given by Artur Rubinstein? One that shouldn’t ever have loud sounds in his music, just smoothed-out plateaus?

What if someone four months younger than Debussy plays him with a forte? Moriz Rosenthal (1862-1946), taught by Chopin’s assistant Mikuli and Liszt, friend of Brahms and Charles Rosen’s teacher

recorded Reflets dans l’eau in 1929 on a Bechstein piano:

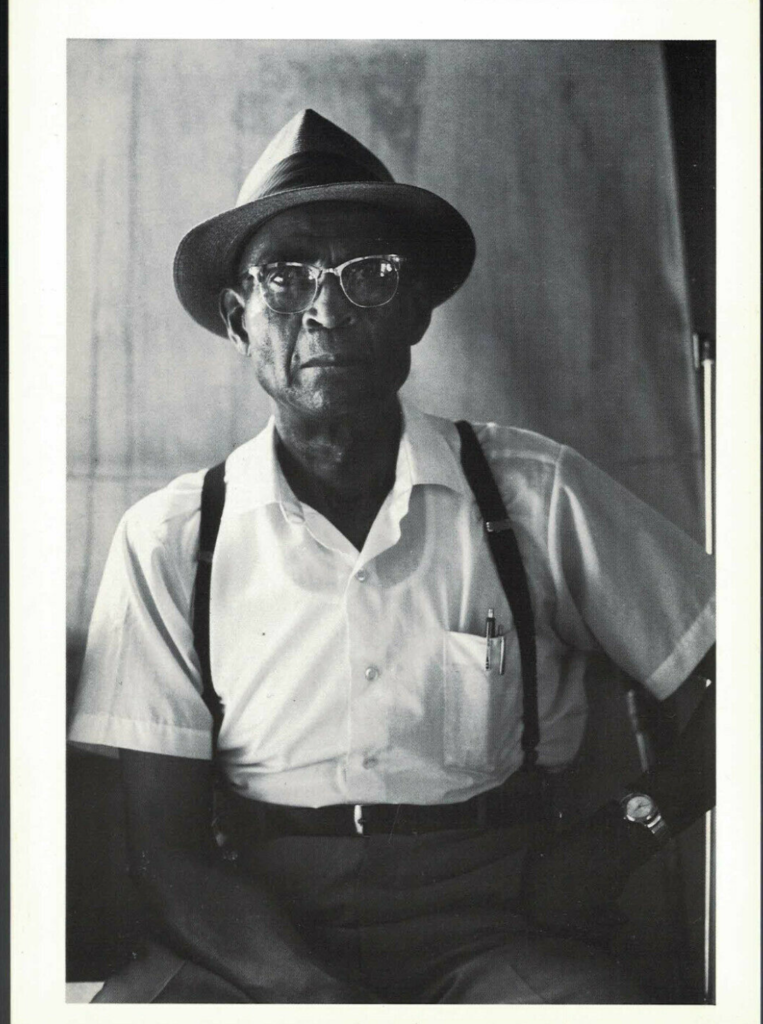

It operates as a cultural virus. Stops over. Infects imaginations and off it goes, either to Memphis Tennessee or Paris France. A tavern in the Mississippi Delta was such a fertile ground for developing and sharing new music. Robert Wilkins, before he became an ordained minister, sang about one such lost paradise (lower photo: Rev. Wilkins with Nehemiah “Skip” James):

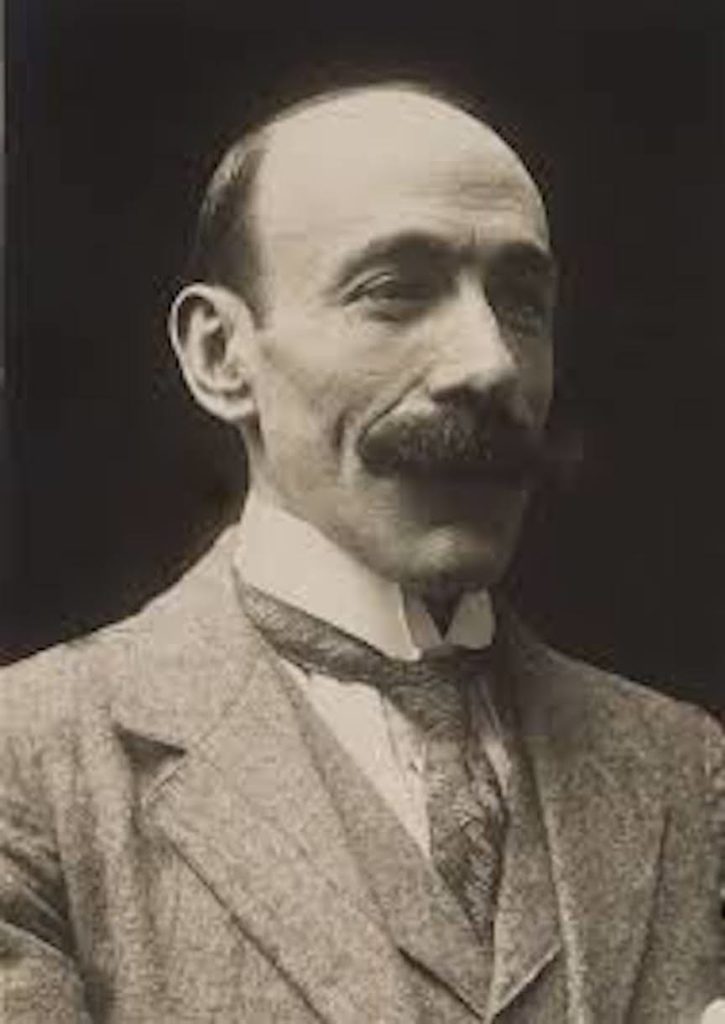

We find Ricardo Viñes (1875-1943)

a newcomer to Paris who was studying along with Ravel and premiered many of Debussy’s works, such as the Poissons d’Or that the composer dedicated to him. Luckily he recorded it and the Soirée dans Grenade in 1930:

Images, Bk. II: Poissons d’Or:

Estampes: Soirée dans Grenade:

Exploring music from a country that he never visited, Debussy wrote La sérénade interrompue in his Préludes Bk.I. The pianist Janine Weill was a shy too young (1903-1983) [sorry, no photo as of yet!] to have known Debussy but hosted a series on French Radio in the 1950s to offer his complete piano works with commentary. Around 1929 she recorded the sérénade:

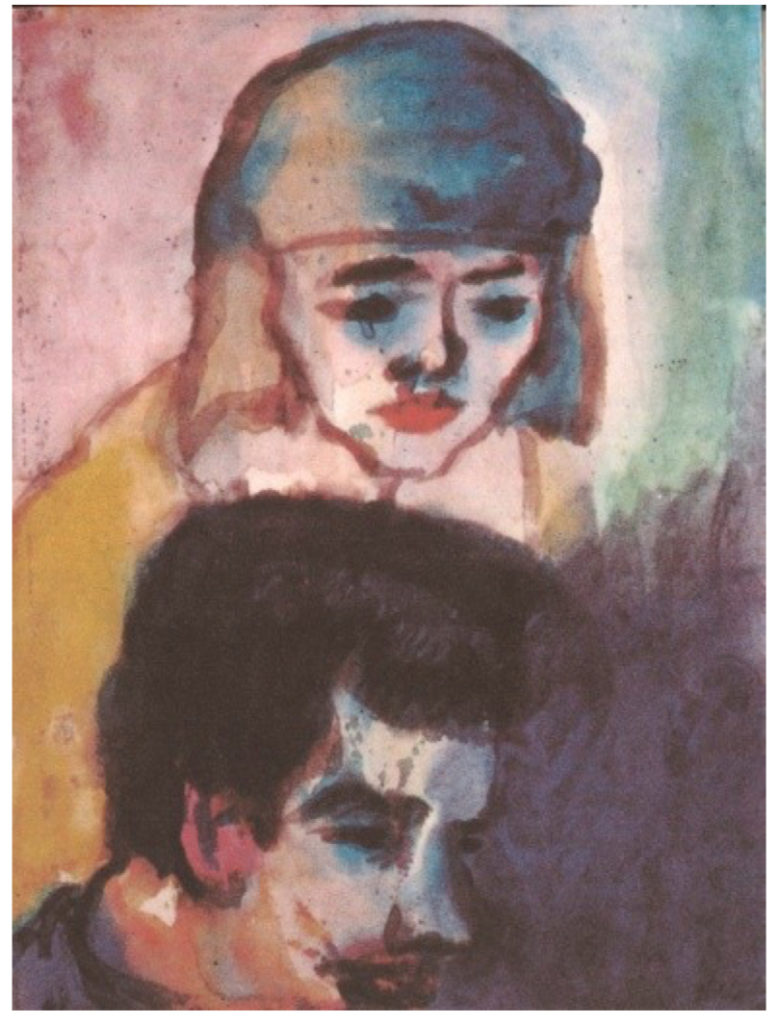

Debussy had a great admirer in Berlin. The pianist & composer Eduard Erdmann (1896-1958) acquired a rep for playing Bach’s Goldberg Variations (long before Glenn Gould), William Byrd, late Liszt, Schubert sonatas, Schoenberg and more. He married Irene Nolde, daughter of the painter Emil, who left portraits of his son-in-law, whose habit was to arrive for his concerts dressed in tuxedo on bicycle. Husband and wife:

Does #hetoo violate “community” standards by not using a steam-roller to repress loud sounds? Erdmann offered us Ondine, from Debussy’s Préludes Bk. II captured at a Berlin studio in 1928:

Another virus struck Paris when African-American dancers, acrobats and musicians arrived. Debussy often saw these cabaret artists and set them to his music.

![]()

![]()

The Russian Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

was not immune to their charm and in 1921, recorded Golliwog’s Cakewalk from Debussy’s Children’s Corner Suite into a horn (before microphones appeared):

Erdmann’s other Debussy solo lives on the other side of his shellac: Minstrels, the last in Préludes, Bk I:

Meanwhile, Galina Werschenska (1906-1994)

left Petersburg soon after the Revolution to settle in Denmark, where she enjoyed a full career, authored memoirs and translated Turgenev into Danish. One work by Debussy is to be found in her legacy: Snow Is Dancing, from the Children’s Corner Suite:

Her bringing us into an alternate dimension follows a tragectory that initiated in Debussy’s first masterpiece, his String Quartet from 1892-93. The music forms itself throughout, from this moment and up into his final works, despite the formal formalities that academics use to appraise composers’ cultural market value. The Loewenguth String Quartet

was founded by violinist Alfred Loewenguth (1911-1983) when he was 18 (1929) and lasted into the 1970s. We hear in the Third movement an ongoing conversation in which the viola solos with an alto sax timbre (mid 1950s recording). Once in New York they headed over to record Beethoven’s Late Quartets in Rudy van Gelder’s studio. I phoned the late legend and he drily informed that it had been his only classical session: regrettably the sound is distorted and one also wonders why Jimmy Garrison’s bass on van Gelder’s Coltrane sessions is usually inaudible.

These examples are a reminder of how music breathes as long as each work, that was always new music, is offered as an original, organic form, a creation that emerges alive and in need to be kept fit rather than reduced into the standardized faux politeness that reigns as living room status-quo standards.

©Allan Evans 2019

Our CD tribute to Claude Debussy:

Your blogs are reaching new heights of content and interest. More!