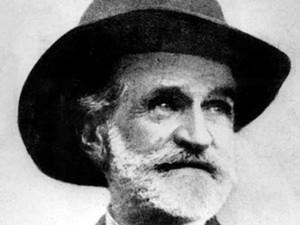

The great Italian opera traditions that exploded in the 19th century are primarily due to Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901). Not only were singers and their public smitten by his new approach and the association of his name with the Risorgimento’s nationalistic purposes but composers such as Franz Liszt were arranging complex and layered operatic scenes for virtuosic piano solos. One enigmatic master, Vladimir de Pachmann, recorded the Rigoletto paraphrase three times: here’s his second version, recorded in 1911 across the river from Philadelphia in Camden, New Jersey, playing into a horn that engraved his sounds into a wax master that later was plated to stamp out shellac 78rpms.

Pachmann’s dates (1848-1933) overlap a sizable part of Verdi’s maturity. His deft capturing of Liszt’s translation of the excerpt into a solo performance attests to an informed and and lyrical sense guided by a taste that understood his opera genre, possibly familiar through performances in the late 19th century.

1901 may seem like a distant time, unattainable to go directly to Verdi himself, but one of his great creators and champions, Francesco Tamagno (1850-1905) was recorded two years after the composer’s death. Born in Torino (Turin) to an innkeeper, a vivid description is in Mario Corsi’s biography of the singer:

“Once there were many trattorias around the lower class Porta Palazzo section, but one run by Carlo Tamagno, under the insignia proclaiming it as The Centaur along the edge of the Dora, enjoyed a certain fame: above all due to the culinary connoisseurs who appeared at any hour of the day for an excellent fish fry, which was caught at the moment, in a net, always available, just steps away on the river bank, for which the trattoria became commonly known as pesci vivi (“live fish”), and also because the host was a simpatico giant of a man, a bit coarse in his manners but reserved and good-hearted just like the wine in his barrels, a great gentleman.

“The clients knew his weak spot: they knew he was proud to possess a beautiful tenor voice – and therefore there was nothing lacking in his singing, not even lacking the passion of singing, so when in the mood and finding the right moment, he was able to offer a taste of his voice, which gave him the same pride as his fish and wine.”

Not long after the birth of his son Francesco:

Italy became embroiled in a movement to gain independence and unity, spearheaded by Garibaldi and Verdi on the musical front. Francesco Tamagno’s talent was noted at once in such an environment and his art and career developed rapidly, leading to North and South American tours. Verdi created his role Otello for Tamagno, and his interpretation became a startling emblem of Verdi’s new music.

Many recordings by Italian singers began to proliferate as soon as the Gramophone & Typewriter Co. set up their studio inside a Milanese hotel room in 1901, nabbing Enrico Caruso and other current stars. Tamagno was ill, in retirement, and could not venture to the studio, so two years after Verdi’s death, the G&T crew carted their gear to his holiday villa and in 1904 another session took place in Roma. These examples of his art reveal the depth of Verdian drama and style in a way that later singers rarely experience or approach: a few excerpts are from Otello – recorded within two years of the composer’s passing. Our newly created restoration technology makes his voice so present that the demands it inflicted on the fragile recording horn are palpable. Listeners are advised to pretend the background shellac noise is a rainfall outside the Villa.

An aria in Il Trovatore, Di quella pira, serves as an introduction to his voice’s body, control, projection, and drama:

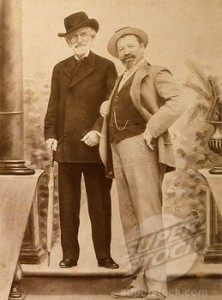

The surface of this aria’s message and style would deepen as Verdi worked with Tamagno and developed their Otello. Hear its creator sing the Death of Otello: Verdi is above Tamagno, who would otherwise tower over him.

A very expressive photo of the elderly composer with his dynamo interpreter reveals their affinity for one another’s art and character.

The demand for remarkable tenors grew and is still exemplified by Caruso, who hailed from Napoli which had existed for centuries as a Bourbon colony under the Spanish, ruled as their Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

His songful Neapolitan dialect is far from Northern Italy’s and a 1915 recording of the pop song O Sole Mio displays a Spanish holdover by moving to a habanera rhythm. Caruso’s tenor is caught in a new restoration:

Caruso was dragged through a commercialization process, one that neglected to fully document his roles or go beyond popular kitsch yet he remains as a cultural icon, as does the later and lesser Pavarotti but Tamagno’s art outlasts the limits of their style and musicianship, a singer who probably sang himself to death by stressing his body for Art, dying at age 55. Here we close by offering Otello’s entrance: Esultate (recorded one hundred ten years ago, in 1903), a direct opening into Verdi’s surroundings:

©Allan Evans 2013

Hello! This comment is on a separate topic. I am a huge fan of Rev. Gary Davis and I love “The Sun of Out Lives,” the entire thing is so well-written. But I am particularly interested in Elizabeth Harold’s typescript. I am searching for it, and seeing you have an excerpt- is there any way you have the whole thing? It would be a dream come true to read that text.

Sincerely,

JW

Ms. Harold’s daughter is preparing it for publication. It may take some time but the project has begun.

Once there is news it will be shared on our blog. Thanks for your interest in Rev. Davis! He also participated in “Black Roots”, a roundtable discussion filmed c. 1969 by Lionel Rogosin and was recently restored for DVD release in a few weeks as part of a set including his Come Back, Africa: http://milestonefilms.com/products/come-back-africa