After completing a decade long Balinese project to retrieve and publish the lost 1928 recordings, I headed over to Paris to spend time with the pianist Henri Barda

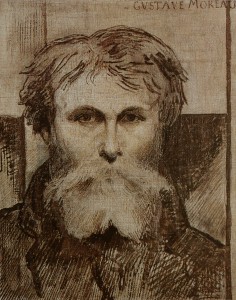

who had recently played Brahms’s Op. 118 with a Chopin group in Brussels. His musical pianism is exemplary and inspiring and no one has approached his Ravel! A new path opened after seeing a painting at the Musée Orsay that led to my stumbling into Gustave Moreau’s home and studio across the river near Trinité, where Messiaen deputized as organist:

Back home with my head spinning from Barda, Moreau, Restaurant Lao-Viet, choucroute garni, and Le Maison du Mièl, a New York piano festival offered a Scriabin lecture with brilliant playing and comments by Dmitry Rachmanov.

His music often remains a lesser priority for the multitude of Rachmaninoff lovers and we chatted about the way he receives adulation from nearly every pianist raised in Russia and the Ukraine: all seem to revere his music as a primal spiritual experience.

It provoked a desire to chart an expedition into Scriabin’s legacy and find possible directions that developed and emerged from him, Rachmaninoff, and the other fall-outs after the Soviet Union developed a new culture. Poetic playing characterized the best of Russia’s pianistic art before the Revolution, one that gave way to a harsh, athletic goal of industrial strength that dominates the background in Soviet playing and pedagogy. Let’s bypass them all to how hear earlier Russian masters convey a once-thriving elegance, poetry, and sung narrative that pervaded their 19th century’s aesthetic, one that cloyingly dissipated during their Silver Age, a parallel of Huysmans’s reaction to Moreau’s art. I urge you to skim the facts and attempts to place the players in any sort of constellation or order, rather to listen and hear it through their ears.

Scriabin left Russia to explore Theosophy in Switzerland. We haven’t a trace of his own playing, aside from inaccurate mechanical approximations of the player piano rolls he left. A South African business man residing in Russia could have lured Scriabin to record on his cylinder machine but didn’t. There are other Russians from Scriabin’s time (1872-1915) who knew him and his playing. A schoolmate of his in Zverev’s boarding stable was Konstantin Igumnov (1873-1948),

a pianist who knew Tchaikovsky, one who furtively arranged the visiting Henry Cowell to meet with colleagues and students in private and challenged the officials by arranging a concert for the young composer. Igumnov emanates fresh air amidst the stale Stalin regime by playing Scriabin’s Poème, Op. 32, No.1 ( recorded in 1935.) Its flirtatious vagueness slyly eludes the obligatory confinement assigned to a basic melody expected by the reigning Socialist Realism:

Slightly younger, Elena Bekman-Shcherbina premiered works by Scriabin and received his approval. Her artistry was on a higher level than the heralded male colleagues who were regularly summoned into recording studios. On the cosmic scale, her too few examples place her art above the others. Her poetic, colorful touch remained up to the end of her life. Bekman-Shcherbina (1882-1951) played this same Poème one year before her life was over:

Another young man found acceptance from Scriabin and left us four sonatas. Samuil Feinberg (1890-1962)

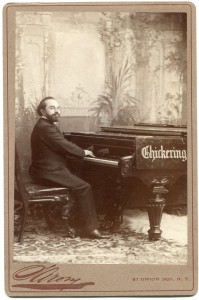

had been taught by Alexander Goldenweiser (1875-1961),

who had spent considerable time in Tolstoy’s company (photo: Goldenweiser on the far right) and left a book of their discussions that was abridged in Virginia Woolf’s collaborative English translation. Feinberg composed concertos, piano solos, and songs, imbuing his playing of Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 2 from a composer’s vantage:

A decade younger, Alexander Kamensky (1900-1952)

was a contemporary of Shostakovich and Sofronitsky. Again we hear someone playing too poetically to have been idolized in the Soviet culture, remaining an important teacher and dying young. Two Scriabin preludes (Op. 16, No. 4 and Op. 27, No.2) give an idea of his individuality and its roots:

If we reach further back in time, the first sounds of a master pianist come from the Odessan Vladimir de Pachmann (1848-1933).

A great deal of information on him and an interview with his son Leonid are in our Music Resource Library. Pachmann knew Liszt and had lessons from Vera Kologrivoff Rubio, Chopin’s last assistant. His playing represents a mixture of mid 19th century styles, heavily influenced by the bel canto style that Chopin incorporated into his works in an improvisatory way. Pachmann had allowed only the second half of his 1912 recording of Chopin’s Ballade in A-flat, Op. 47 to be published. With earlier playback of ancient shellacs, critics and listeners downgraded Pachmann’s artistry by basing their opinions on inadequate restoration. New technology allows us to experience the shading, tone color, and projection not believed to have existed on acoustic pre-mic recordings:

Some twenty years younger than Pachmann, we are drawn to Vassily Sapellnikoff (1867-1941),

who performed under Tchaikovsky’s baton. He fled the Bolsheviks by swimming across a river to safety in Poland and spent his final years in San Remo, Italy. Instructed by Liszt’s pupil Sophie Menter, who once brought him to meet her teacher, Sapellnikoff portrays the melodic emphasis that was exploited by Liszt’s transcription of the Schumann Frühlingsnacht for piano solo, played by Sapellnikoff for an acoustic horn around 1922 in London:

Maria Safonoff,

daughter of an influential teacher and conductor Vasily Safonoff, escaped to Italy after the Russian revolution and lived in New York until c. 1990-1. She once described how once while her father was napping, Scriabin eased over to the piano and played his soft his Prelude in D-flat from Op. 11 and how her father commented that he was being transported from his dream to a waking one. An idea of her art is heard in Chopin’s Etude in A-flat, Op. 25, No.1:

Back to Rachmaninoff (1873-1943): was his playing shaped by such influences? Today his melodies are made prominent, whereas we hear him skirting their obviousness to have them challenged by the surrounding figuration, an early footstep towards Modernism and Deconstruction.

The composer was a startling interpreter of his works and evoked transformations through his playing of other composers. Felix Salzer, a music theorist, was a Viennese pupil Schenker and member of the Wittgenstein family. Once I asked this severe scholar which pianist had impressed him the most and he shouted out Rachmaninoff!!

“He walked out onto the stage, so stern, his severe haircut and expression, and quietly sat down and out came such sound!” Few have experienced his own playing since most restorations of his recordings are compromised to resemble the quiet playback of vinyl, destroying nuances and balance in the process. With new technology we can experience his vivid sound in his Humoresque, and hear how it influenced the younger Vladimir Horowitz:

If you wish to hear how piano-rolls capture a performance like the one above, try this:

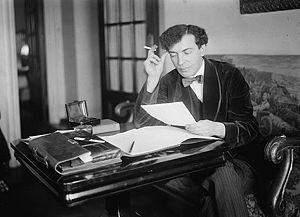

Prokofiev (1892-1953) arrived shortly after Rachmaninoff’s launch. His musical training came from Esipova, a Leschetizky pupil.

A video finds him playing at his cosy dacha, using a body language common to Paderewski and Moiseiwitsch, his musical colleagues. Prokofiev’s works tend to be harsh but his older way of shaping tone underlines the Suggestions Diaboliques:

As Igor Stravinsky became the dominant Russian figure, his son Soulima Stravinsky (1910-1994) arose as an early champion of his father’s music which he played as his native tongue.

He was instructed by Isidor Philipp, a central teacher and protagonist in the Parisian scene. This combination of Russian roots with French training left a precedence that shaped a model that many would later follow. Two of his father’s early Etudes, the pianist’s first solo recordings made in the Paris of 1939 capture the brooding moods and Silver Age forms.

Another Russian expat was Nikita Magaloff (1912-1992),

who resided primarily in Switzerland, above Lac Leman in Clarens where Stravinsky composed his Rite of Spring. Also a student of Philipp’s, Magaloff inherited several traditions from partnering his father-in-law Joseph Szigeti who had worked with Bartók and from contact with Stravinsky and the practiced aesthetic of his time for Russians to align themselves to emerge by expanding their Francophilia. One evening he gave an impressive Chopin recital in New York, playing the Ballades and Scherzi, of which we hear the Fourth Scherzo in E, Op. 54:

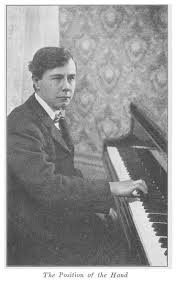

Perhaps the catalyst behind the piano being played more mechanically came from a Polish pianist who generated hysteria on Russian musical stages in part due to his eschewing of the 19th century’s focus on lyricism by favoring a more compartmentalized approach. Josef Hofmann (1876-1957)

had given years of recitals in pre-Soviet Russia and was advised in Dresden by Anton Rubinstein, the pioneering founder of Russia’s absorption of the piano. A disc made in 1916 of a tarantella in Liszt’s Venezia e Napoli exhibits a tendency that led to the dominance by the Moscow Conservatory’s mannerisms of profiling high and low notes with the middle material a mush:

Rachmaninoff admired how Benno Moiseiwitsch (1890-1963)

played his music. A striking contrast separates Rachmaninoff’s avoiding overt themes from Moiseiwitch’s drawing them into a more emphatically melodic and streamlined strand. Through him and others, a 19th century background has been remade into an objective linearity. One hears it happening in Ravel’s Toccata‘ from the Tombeau de Couperin as frenetic repetitions and jagged figuration are smoothed into a tightened one-dimensional foray. This phase comes as a turning point that would either compel pianists to choose looking backward or attempt a redefining of the piano into a percussive or ever-more conceptual instrument: the 19th century’s feasting was over and done with.

Allan Evans ©2015

![Magaloff-Nikita-09[1986]](https://arbiterrecords.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Magaloff-Nikita-091986-300x229.jpg)

What a treasure. Thank you for your tireless, invaluable work.