Bartók was a good listener, especially when transcribing with scientifically accuracy thousands of field recordings made during his excursions into the lands where peasants lived. He owned a tekerő, the Hungarian peasants’ version of what is called a hurdy-gurdy.

He and Kodaly had learned of Debussy some time before the Frenchman arrived in 1910 to perform solos, accompany a singer, and hear his String Quartet being introduced in Budapest. It seems that Bartók missed the concert but soon began absorbing Debussy’s music. Soon after Bartók arrived in Paris he was asked by Isidor Philipp if he wanted to meet composers close to this French pianist. Bartók’s colleague André Gertler,

with whom he toured to give sonata recitals. In 1960, Gertler recalled:

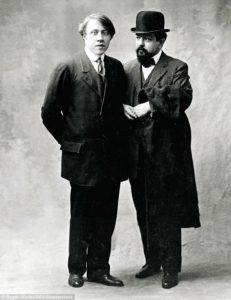

The meeting never came about. Perhaps it would have resembled Debussy seen with André Caplet?

We’re not sure if Etelka Freund, Bartók’s older friend who was a direct link to Brahms, had attended the Budapest evening. She was expecting a child but like Bartók, added Debussy’s music to her repertoire. With Dita Pasztory, a pupil who became Bartók’s second wife, he formed a piano duo with her. One work they performed was Colin McPhee’s Balinese Ceremonial Music for two pianos, an interest that he and Debussy shared for Asian music.

Always insightful to hear a composer perform another’s works, Bartók recorded Liszt’s Sursum Corda while staying in Paris in the mid 1930s:

This late work finds Liszt entering into dissonance, whole-tone scales and figuration that may have inspired Bartók at a deeper level.

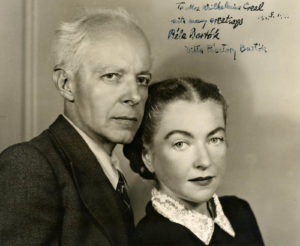

A devoted admirer of Bartók’s playing, the author Ilona Tanner was the wife of poet Mihaly Babits (seen together in this photo.)

While Babits is recognized, Tanner’s astonishing request that a local record shop make private recordings for her whenever Bartók played on the radio saved a rare musical legacy that amounted to a few hours of concerts. Lacking blank recording discs, the shop owner found that x-ray plates could be used for recording sound. At first he had one machine and had to miss music as the sides could only capture four minutes when changing discs: he soon acquired a second instrument. One of the treasures she saved was the duo’s performance of Debussy’s En Blanc et Noir in April, 1939. Images of chest bones and other body parts did not cause lacunas due to switching discs on the recording table nor create the weak sound that took quite awhile to clear up: new digitization is urgent as playback and restoration techniques have advanced, before the plates decay or managers ordering an engineer at French Radio to trash noisy discs, such as Bartók’s 1939 Paris recital:

Another temporary duo kept the work alive by playing it several times at prominent 1950s new music festivals such as Darmstadt: Yvonne Loriod (coached by her husband Olivier Messiaen) and Pierre Boulez, seen here after a 1956 performance.

Although we have published other posts on Debussy and a CD with the most insightful interpreters to date, more posts will follow so check back now and then!

Allan Evans ©2019

and more links to Debussy: