It came as a shock to hear such Debussy. About Marius-François Gaillard all one could instantly find was that he recorded works by Debussy in Paris around 1928-1930. No idea of his age but the pianism went beyond those who confine their entire Debussy into their own prefabricated styles. With Gaillard each piece was a world unto itself, showing how Debussy reinvented the piano and himself in each composition. It came as a relief to hear the music emerge that had been missing when brand-names like Gieseking and Cortot rushed through or neglected to expose Debussy’s ingenuity and subtlety. As a composer, Gaillard understood why each note exists and projects the micro within the larger scale. Later on Gaillard would draw on his travels and contact with traditional world music in his own works.

Gaillard (1900-1973) emerged on the Paris scene when he made a debut at age 16 after winning a prize thanks to refinements by Louis Diémer (1843-1919), an Alsatian master who helped revive the harpsichord already in the late 19th century.

Early Gaillard programs included new French music and Mozart concertos. A review appeared in 1922 by the writer Henry Malherbe (1886-1958) who knew Debussy and elicited these comments from the composer, something that informed his impression of the man who was still playing on occasion:

After the premiere of Debussy’s Saint Sebastian:

I believe indeed in a renaissance of liturgical music. Sacred art flourishes nobly only under persecution. And since wrong is being done to the Church, as it seems [sic], I think that the atmosphere is propitious for religious scores.

For me, sacred music stops at the 16th century. The charming and spring-like souls of those days were the only ones who could express their vehement and disinterested fervor in songs free from all worldly taint. Since then pious musical improvisations have been made more or less for parade. Even the genius of that naif and worthy man, Johann Sebastian Bach, did not save him. He builds edifices of harmony, like a great and devout architect, not like an apostle.

Parsifal is pretty. It is theatrical, which is poison to simplicity. Wagner himself calls his works spectacles. He was too well fortified against humility to celebrate religion. His attitudes are too dramatic for prayer. His proud and factitious theories never leave him.

Who will feel again the grandiose passion of a Palestrina? Who will begin again the poor and fragrant sacrifice of the little jongleur, whose story has come down to us?

Music is a sum of scattered forces, (he said to a personage of his own invention, M. Croche in Entretiens avec M. Croche, in the Revue blanche, 1901) . . .

People make theoretical songs of them! I prefer the few notes from the flute of an Egyptian shepherd: he collaborates with the landscape and hears harmonies unknown to our treatises. Musicians hear only the music written with clever fingers, never that which is written in nature. To see the sunrise is more useful than to hear the Pastoral Symphony. What good is your almost incomprehensible art? Ought you not to suppress these parasitic complications which make music in ingeniousness like the lock of a safe? . . . You boast because you know music only, and you obey barbarian, unknown laws! You are hailed by fine fine epithets and you are only rascals-something between a monkey and a valet!

I was dreaming. Formulate oneself? Finish works? So many question-marks placed by a childish vanity, the need of getting rid at any cost of an idea with which one has lived too long; all this poorly concealing the silly mania of fancying oneself superior to both.

Before a moving sky, (he said to M. Henry Malherbe) contemplating for hours together the magnificent constantly shifting beauty, I feel an incomparable emotion. Vast nature is reflected in my literal, halting soul. Here are trees with branches spreading toward the sky, here are perfumed flowers smiling on the plain, here is the gentle earth carpeted with wild grasses. And, insensibly, the hands take the position of adoration . . . To feel the mighty and disturbing spectacles to which nature invites ephemeral, temporary passers-by . . . . that is what I call prayer.

Who will ever know the secret of musical composition? The sound of the sea, the curve of the horizon, the wind in the leaves, the cry of a bird deposit in us multiple impressions and suddenly without our con- senting the least in the world, one of these memories speaks out of us and is expressed in musical language. It carries its harmony in itself. Try as we will, we cannot find a harmony more just or more sincere. Only in this way, does a heart destined to music make the most beautiful discoveries.

That is why I wish to write my musical dream with the most complete detachment from myself. I wish to sing of the inner landscape with the naive candor of childhood.

This innocent speech will not make its way with stumbling. It will always shock the partisans of artifice and falsehood. I foresee that and rejoice in it. I will do nothing to create adversaries. But I will do nothing to change adversaries into friends. One must force oneself to be a great artist for oneself and not for others. I dare to be myself and to suffer for my truth. Those who feel as I do will love me only the more for it. The others will avoid me, will hate me. I shall do nothing to conciliate them.

In truth, on the distant day– I must hope that it may come later– when I inspire no more quarrels, I shall bitterly reproach myself. In those last works, there will necessarily dominate the detestable hypocrisy which will have permitted me to satisfy everybody.

–Debussy to Malherbe (Excelsior, 11 Feb. 1911)

In May 1910 Claude Debussy said to Prudhomme: “Every artist has his temperament: art is always progressive; it cannot then return to the past, which is definitely dead. Only imbeciles and cowards look backwards. . . In conclusion: Let us work!”

Gaillard was the first to offer Debussy’s then-complete piano works in three evenings.

Malherbe was there each evening and write of his experience:

Debussy interpreted by Marius-François Gaillard

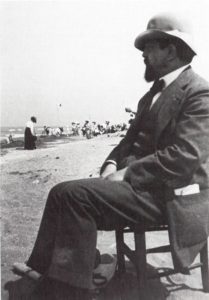

Nothing seemed to me more strange. And, however, nothing was simpler. Under the alternating fires of two spotlights, a very young man, with troubled eyes and flaming hair, was seated before the black mass of a piano. And, alone, confronting a considerable public, delirious or collected, and who filled the vast ship of the room of the Opera of the Champs-Elysees.

This spectacle still besets my memory.

For three nights, Mr. Marius-François Gaillard renewed a feat that remains unique in modern music. He played by heart – never was the expression more circumstantial – the complete piano works of Claude Debussy.

The young and prodigious executioner had, in truth, recourse to his memory. He seemed possessed of some mysterious fervor. His fast hands, endowed with a supernatural frenzy, restored to us, with an infallible accuracy, the Arabesques, Ballade, Reverie, Nocturne. Valse Romantique, the Preludes, Estampes, Images, Etudes, and all the works for piano by the great musician of Pelleas.

For his swarthy complexion, his hair and beard curly and too brown, for his sparkling eyes, black and sunken under the gilded and sovereign forehead, we called Claude Debussy The Prince of Darkness.

Did we live the other night in a hallucination? The Prince of Darkness was there, alongside his masterly performer. Did Gaillard so miraculously play only because he received from him that ineffable presence? Of this hard percussion instrument, which seems to be made, especially, for dry compositions, geometric, colored by points, juxtaposed spots (something like, in another field, the paintings of Cross or Signac) M. Marius-François Gaillard offered a melted, voluptuous music, a dripping poetry, deep shades, muted, airy subtlety, vibrant freshness, melancholic graces and admirable enveloping orchestral effects.

I seek to characterize, with some certainty, a kind of genius that burns in this young and great artist, when he plays the works of his favorite master. Today I’m desperate to reproduce my thought. The words come like crowds into my mind, in the tumult of feelings that agitate me. I can not choose. In these hastily sketched lines I no longer propose to present to you the study which I wish to publish on Gaillard, Debussy’s interpreter. To make these impressions lasting and to judge them with strength demands a long effort.

So I express, at least, the convictions that leave us these three unforgettable evenings where Marins-François Gaillard played, by heart, all the piano works by Claude Debussy:

l.) Debussy, as in the theater and the symphony, has brought into pianistic music an absolutely new style.

2.) Debussy has pulled from the piano a fabulous and unsuspected wealth and the work he leaves. for this instrument, is perhaps the most important of all pianistic literature.

3.) Among the illustrious interpreters of this incomparable musician, Marius-Francois Gaillard has proved to be the most truthful, the most inspired, the one whose action is most striking to an audience.

In a future article, I will try to develop these findings carefully.

Henry Malherbe

Choses de théâtre, cahiers mensuels de notes, d’études v.1, 1921:Oct.-1922:July –1923.

The original, for our French readers:

Debussy interprété par Marius-François Gaillard.

Rien ne me parut plus étrange. Et, cependant, rien n’était plus simple. Sous les feux alternés de deux projecteurs, un tout jeune homme, le regard trouble, la chevelure en flammes, était assis devant la masse noire d’un piano. Et, seul, affrontant un public considérable, délirant ou recueilli et qui remplissait le vaste vaisseau de la salle de l’Opéra des Champs-Elysées.

Ce spectacle assiège encore mon souvenir.

Pendant trois soirs, M. Marius-François Gaillard a renouvelé un exploit qui demeure unique dans la musique moderne. ll a joué par cœur, — jamais l’expression ne fut plus circonstancielle, —- tout l’œuvre pianistique de Claude Debussy.

Le jeune et prodigieux exécutant avait-il, en vérité, recours à sa mémoire. Il semblait possédé de je ne sais quelle ferveur mystérieuse. Ses mains rapides, douées d’une frénésie surnaturelle, nous restituaient, avec une justesse infaillible, les Arabcsques, la Ballade, la Rêverie, le Nocturne. la Valse romantique, les Préludes, les Estampes, les Images, les Études, et tous les ouvrages pour piano du génial musicien de Pellëas.

Pour son teint basané, ses cheveux et sa barbe frisés et trop bruns, pour ses yeux étincelants, noirs et enfoncés sous le front doré et souverain, nous appelions Claude Debussy Le Prince des Ténèbres.

Vivions-nous, l’autre soir, dans l’hallucination? Le Prince des Ténèbres était là, aux côtés de son magistral interprète. Gaillard n’a-t-il si miraculeusement joué que parce qu’il entait, auprès de lui, cçtte présence inelfable? De ce dur instrument à percussion qui parait fait, surtout, pour des compositions sèches, géométriques, colorées par des points, des taches juxtaposées (quelque chose comme, dans un autre domaine, les tableaux de Cross ou Signac) M. Marius-François Gaillard obtient un fondu, des êtirances voluptueuses, une poésie ruisselante, des teintes profondes, amorties, une subtilité aérienne, des fraîcheur rieuses, des grâces mélancoliques et l’admirables effets enveloppants d’orchestre.

Je cherche à caractériser, avec quelque certitude, une sorte de génie qui brûle en ce jeune et grand artiste, lorsqu’il joue les œuvres de son maître préféré. Je désespère de reproduire, aujourd’hui. ma pensée. Les mots viennent en foule à mon esprit, dans le tumulte des sentiments qui m’agitent. Je ne saurais choisir. En ces lignes, hâtivement tracées, je ne me propose plus de vous présenter l’étude que je voudrais publier sur Gaillard, interprète de Debussy. Pour rendre ces impressions durables et les juger avec force, il faut un long effort.

Que j’exprime, pour le moins, les convictions que nous laissent ces trois soirées inoubliables où Marins-François Gaillard joue, par cœur, tout l’œuvre pour piano de Claude Debussy:

l.) Debussy, comme au théâtre et à la symphonie, a apporté dans la musique pianistique, un style absolument nouveau.

2.) Debussy a tiré du piano des richesses fabuleuses et insoupçonnées et l’oeuvre qu’il laisse. pour cet instrument, est peut-être la plus importante de toute la littérature pianistique.

3.) Parmi les illustres interprètes de ce musicien incomparable, Marius- François Gaillard s’est révélé le plus véridique, le plus inspiré, celui dont l’action frappe le plus vivement un public.

Dans un prochain article, j’essaierai de développer soigneusement ces constatations.

Henry Malherbe

Choses de théâtre, cahiers mensuels de notes, d’études v.1, 1921:Oct.-1922:July –1923.

Unlike Cortot, Gaillard was not in favor of the Nazis and their French puppets. One academic claimed that Gaillard’s post-War career was dampened by possible associations with the regime. An account by a hero of the Underground dispels this speculative fallacy to show how Gaillard was active in the opposition:

Paul Steiner

Here is living testimony from Paul Steiner, national president of the “Resistance” Movement, member of the Friends of the Resistance.

I was born in Paris in April 1922 and I quit studying at the Condorcet at the end of the second class in July 1938 in order to exclusively dedicate myself to my violin studies that began at age seven.

I was a student of Marcel Darrieu, solo violinist at the Colonne Orchestra’s concerts.

Eager to move into a string quartet at the end of 1938 I became a pupil of Gabriel Bouillon, professor at the Paris Conservatory who led a noted string quartet. His brother Jo Bouillon married Josephine Baker after the war. In the summer of 1939 I received a First Prize and was engaged as first violin with the Colonne Orchestra.

When the war broke out the Germans demanded that the concerts would be called the Gabriel Pierné Concerts because Édouard Colonne was Jewish.

At the end of 1940 I was also engaged as first violinist by Marius-François Gaillard and his orchestra of forty musicians. Gaillard, born in 1900, was Claude Debussy’s favorite pupil of whose almost complete works comprised a 1922 world tour to New York, Tokyo, etc. [This is not entirely accurate.] He was a perfectionist and his [orchestral] concerts were primarily comprised of works by Mozart and Schubert were notable. German soliders and officals came in great numbers and the orchestra often played on Radio Paris. Already by September 1942 I knew Jacques Destrée, who had just become one of the founders of Resistance, a secret newspaper. He had great confidence in me and I was hired as a secretary and part-time assistant.

I had in hand a hundred or so copies the 21 October 1942 issue, just released, of Resistance, number 1. Marius-François Gaillard was electrified when I gave him several copies to bring over to musical, literary, and artistic circles. The amount rapidly grew from 100 to 200 copies.

Meanwhile I took a course in chamber music given by Henri Benoit at the Ecole Normale de Musique, who, between the wars was a violinist in the famous Capet Quartet before joining Gabriel Bouillon’s quartet (my violin teacher.)

I noticed that in this course an elderly lady came for her own pleasure She lived in Dreux, had been a nurse in 1914-1918 and was highly decorated. Her anti-German sentiments were not in doubt and already in October of 1942 she distributed copies of Resistance. By the end of December 1942, I gave her, I believe, al least 50 newspapers and asked if she would consider the idea of creating a group in Dreux. Soon after, there came to me in Paris a M. Maranges, owner of the Peugeot garage in Dreux. This notable man had founded the very large group that organized sabotage in the region without a single arrest, and spoke at length of his efficacy at the moment of Liberation.

At the end of 1942 I was also engaged as violinist with Fernand Oubradous’ wind orchestra that permitted me in the beginning of 1943 to go with the Vichy Orchestra. The concert was organized at the Vichy Theater, I don’t know when, but it was in the presence of Marshall Petain and other high dignitaries from the French regime. With my luggage I brought along 100 copies of Resistance and during the first rehearsal for an hour or two I went to put my newspapers being very careful to place them in the loges, balcony seats and on the floor. I must say that I don’t recall all the seats. Fernand Oubradous had a problem because the police, in fact, that had to have been one of the 35 or 40 members of the orchestra that had “brought over these papers from Paris.” But as it was in the minds of the collaborators I had much to do with this opportunity. When I got back to Paris I was telling Jacques Destrée about my personal initiative, at first he laughed but right after he dug into me but also with affection for having undertaken such a risk, given my position with him.

When in the beginning of 1943 there was the problem of STO (Service for Obligatory Work, deporation by the Nazis to work as forced laborers in Germany) for the class of ’42 I had easily registered under a false name with the Colonna (Gabriel Pierné) Orchestra. With Marius-François Gaillard it was normal to hide me under a fake name because we were very good friends. I gave fake documents to other musicians in his orchestra.

Published in http://lesamitiesdelaresistance.fr/journaux.php

and for our dear French readers:

Voici un témoignage vécu de Paul Steiner, président national du Mouvement “Résistance”, membre des

Amitiés de la Résistance.

Je suis né à Paris en avril 1922, et j’ai arrêté mes études à Condorcet à la fin de la classe de seconde en juillet

1938 pour me consacrer exclusivement à mes études de violoniste commencées à l’âge de sept ans. J’étais élève de Marcel Darrieux, violon solo de l’orchestre des concerts Colonne.

Désirant m’orienter vers le quatuor à cordes, je devins, fin 1938, élève de Gabriel Bouillon, professeur au conservatoire de Paris que dirigeait un remarquable quatuor à cordes. Son frère, Jo Bouillon devint après la guerre le mari de Joséphine Baker.

À l’été 1939, je fus reçu premier au concours d’entrée à l’orchestre Colonne et enregistré comme premier violon.

La guerre éclata et les allemands exigèrent que les concerts Colonne s’appellent concerts Gabriel Pierné, car Édouard Colonne était juif.

À la fin de 1940 je fus également engagé comme premier violon par Marius François Gaillard dans son orchestre de chambre de quarante musiciens. Marius François Gaillard, né en 1900, avait été l’élève préféré de Claude Debussy, dont il interpréta vers 1922 la presque intégralité des œuvres pour piano dans une tournée mondiale à New York, Tokyo, etc. C’était un perfectionniste et ses concerts consacrés surtout à Mozart et à Schubert étaient remarquables. Les officiers et soldats allemands y venaient en très grand nombre. L’orchestre jouait souvent à Radio Paris.

Dès septembre 1942 je fis la connaissance de Jacques Destrée qui venait d’être l’un des fondateurs du journal clandestin Résistance. Il eut immédiatement une très grande confiance en moi et me prit comme secrétaire et adjoint à temps partiel.

J’eus aussi en mains dès sa sortie le 21 octobre 1942 une centaine d’exemplaires du n°1 de Résistance. Marius François Gaillard fut enthousiasmé lorsque je lui eu remis plusieurs exemplaires pour toucher les milieux musicaux, littéraires et artistiques. La quantité passa très vite à 100 puis 200 exemplaires.

Entre temps, je suivais les cours de musique de chambre de Henri Benoit à l’École normale de musique, place Malesherbes, qui entre les deux guerres avait été l’altiste du très célèbre quatuor Capet avant de devenir celui du quatuor Gabriel Bouillon (mon professeur de violon).

J’avais remarqué à ce cours une relativement vieille demoiselle qui y venait pour son plaisir. Elle habitait Dreux. Elle avait été infirmière en 14/18 et était très décorée. Ses sentiments anti-allemands ne faisaient aucun doute, et dès octobre 42 je luis remis des exemplaires de Résistance. À fin décembre 1942, je lui remettais, je crois, au moins 50 journaux et lui demandai si elle pouvait envisager de créer un groupe à Dreux. Peu après elle me présenta à Paris, à M. Maranges, propriétaire du garage Peugeot à Dreux. Cet homme remarquable créa un groupe très important qui organisa dans la région des sabotages, sans aucune arrestation, et fit beaucoup parler de son efficacité au moment de la Libération.

Fin 1942, je fus également engagé comme violoniste dans l’orchestre d’instruments à vent, très connu également, de Fernand Oubradous. Cela me permit début 1943 d’aller avec l’orchestre jouer à Vichy. Le concert était organisé au Théâtre de Vichy, je ne sais plus à quelle occasion, mais c’était en présence du maréchal Pétain et de certains hauts dignitaires du régime à la francisque. J’avais emporté dans mes bagages un paquet de 100 Résistance et, pendant la répétition générale précédant le concert d’une heure ou deux, je suis allé poser mes journaux en faisant très attention dans toutes les loges et sur les places du balcon ou du fond de la salle. Je dois dire que je ne me souviens plus très bien de tous les endroits. Fernand Oubradous eut quelques problèmes, car la police avait bien réalisé que ce devait être un des 35 ou 40 musiciens de l’orchestre qui avait “au moins apporté ces journaux depuis Paris”. Mais comme il était très à idées collaborationnistes, j’en avais bien profité. C’était de la folie de ma part, mais tellement tentant d’utiliser cette opportunité. Le concert avait eu beaucoup de succès, mais je pense que Résistance aussi avait dû en avoir pas mal.

Lorsque de retour à Paris je racontais à Jacques Destrée mon initiative personnelle, il éclata d’abord de rire, puis aussitôt après il m’attrapa sérieusement mais aussi affectueusement pour avoir pris un tel risque, compte tenu des fonctions que j’occupais auprès de lui.

Lorsque début 1943 il y eut le problème du STO pour la classe 42, j’ai obtenu très facilement d’être enregistré sous un faux nom à l’orchestre des concerts Colonne (Gabriel Pierné). Avec Marius François Gaillard, ce fut pour lui normal de me cacher sous un faux nom, car nous étions très liés d’amitié. J’ai procuré des faux papiers à deux autres musiciens de son orchestre.

Je pus ainsi tout en m’occupant énormément auprès de Jacques Destrée gagner ma vie en jouant dans les orchestres jusqu’en mars/avril 1943. Jacques Destrée avait besoin de moi à plein temps, car entre temps il m’avait confié la distribution du journal Résistance dès la sortie de l’imprimerie, puis très vite aussi la réalisation technique de l’impression. Au printemps 43 nous tirions toutes les trois ou quatre semaines Résistance sur quatre pages imprimées à 90 000 ou 100 000 exemplaires, soit environ 1 500 kilos en paquets de 100 ou 200 journaux. Ce n’était pas de tout repos de les sortir de l’imprimerie puis en organiser la répartition. C’est ainsi que prit fin ma carrière de violoniste pour me consacrer nuits et jours à l’action clandestine. Au début je dois dire que ce fut très difficile d’abandonner la musique, mais j’étais tellement occupé avec Jacques Destrée que je n’avais pas le temps d’y penser.

Paul Steiner

in http://lesamitiesdelaresistance.fr/lien16-musiciens.php

Meaningless speculation over a diminished career do not stand up to Gaillard’s great passion for the new media of cinema, becoming early on a composer for music to be coordinated with silent film. Gaillard wrote on the necessity to develop a new art form combining both and while it did not materialize in the way Man Ray and Hans Richter’s creations, he had a busy career composing film soundtracks and occasionally conducting his own music, symphonies, and chamber music.

Gaillard’s concertizing as a pianist gave way to his passion for conducting new orchestral music, introducing Varese’s revised Offrandes in 1929. A decade after recording Debussy’s piano works he recorded a Schubert Symphony and Mozart’s #36 with his eponymous orchestra. Here is the Mozart conducted by Gaillard in 1941:

After it’s publication in June, 2018 we discovered a portion of Gaillard playing part of the Hommage à Rameau played in the late 1950s and wish to offer it as Gaillard again reveals insight into this masterpiece:

Debussy (1862-1918) kindly invites you to explore his music and our previous blogs that involve violists who knew him and what went inside his ear:

Allan Evans ©2018

Bravo pour ce travail capital. J’ai le souvenir d’avoir rencontré son petit-fils chez une productrice d’Erato au milieu des années 1980.

Extraordinary essay! Thanks for this brief but quite exceptional investigation and finished article

Bonjour Mr Allan Evans,

Même si je ne suis pas sûr d’avoir éprouvé le choc dont vous parlez à l’écoute du Debussy de Marius-François Gaillard, votre essai reste intéressant.

Une erreur cependant : la 3ème photo utilisée pour illustrer le nom d’Henry Malherbe, écrivain complètement oublié aujourd’hui, est celle du colonel de La Rocque, président des Croix-de-Feu, le principal mouvement “fasciste” français de l’entre-deux-guerres (je mets fasciste entre guillemets car les historiens se disputent encore sur la nature du mouvement, c’était en tout cas une ligue d’extrême-droite).

Une erreur compréhensible car Henry Malherbe en était le vice-président et on lui doit en 1934 un panégyrique de La Rocque sous le titre Un chef Des actes Des idées. Comme son nom ne l’indique pas, cet Henry Malherbe était né en 1887 à Bucarest et était juif. Prix Goncourt en 1917 pour un livre qui exaltait probablement l’armée et le patriotisme (Léon Daudet, ignorant qu’il était juif, avait voté pour lui), puis critique littéraire au Temps, on le retrouve en 1943 en zone sud membre du CNE (mouvement résistant des écrivains) et participant au bulletin résistant Les Etoiles avec des écrivains communistes. Son parcours un peu tortueux est évoqué rapidement dans le livre de Simon Epstein “Un paradoxe français : antiracistes dans la collaboration, antisémites dans la résistance” dont il illustre un peu la thèse. De La Rocque lui-même évoluera de la collaboration à la résistance. Malherbe a signé quelques biographies de musicien bien oubliées. Il semble avoir soutenu que Bizet, confronté à l’insuccès initial de Carmen, se serait suicidé.

L’occupation allemande était un dilemme pour beaucoup et la trajectoire de Gaillard pendant ces années-là ne se résume peut-être pas au seul ‘événement raconté par Paul Steiner. Ce qui est certain, c’est que Gaillard s’était disqualifié comme spécialiste de Debussy bien avant, en 1927-1928, quand, protégé d’Emma la veuve de Debussy, il s’était mis en tête d’orchestrer 3 oeuvres du maître : Salut, Printemps ; Invocation ; Triomphe de Bacchus. Problème : Debussy avait déjà orchestré les deux premières. Cette bévue? à laquelle il faut ajouter la réception plutôt froide de l’Ode à la France terminée par Gaillard et une querelle au sujet d’un monument qui sera portée en justice lui alièneront la sympathie des proches du compositeur, le délégitimeront auprès du public et peuvent expliquer l’oubli dans lequel il est tombé. Le beau livre de Marianne Wheeldon sur la postérité de Debussy donne le détail de ce que j’évoque ici très rapidement.

Je suis quand même surpris de lire que Cortot et Gieseking seraient passé à côté de la subtilité debussyste et aussi décu de ne pas voir évoquer le nom de Ricardo Viñes.

Thanks for your comments. Viñes will appear in a future post. If only he had been contracted to have recorded more works by Debussy and even Ravel. Instead the market was dominated by Cortot and Gieseking. As their recordings outnumber Gailliard’s and Viñes’s, their dominance of an alleged Debussy style have distorted the public’s comprehension of his music for over half a century.

Great site, dude!