Until recently [1991, when this article was penned], few listeners in the prosperous and relatively safe West knew that an otherworldly singing was thriving over in Bulgaria. I first caught the Balkan blues six years ago [1985] in Berlin, close to the wall in the communist Eastern sector on a drab rainy day. Each Socialist Republic maintained a flagship store for hawking their worst nationalistic artifacts: kitsch, cutesy figurines and other alleged items of “culture”. Poland, Russia, Hungary and Bulgaria were in on this racket. A Bulgarian shop carried a few LP’s hard to find west of the wall. While you paid up with Monopoly money East Deutschmarks, a clerk hand-wrapped the record with straw paper. Tucked into my raincoat was a Balkanton LP of the Philip Koutev Ensemble’s arrangements. After a facelift, this same disc was packaged as Mysteries of the Bulgarian Voice, The Mystery on tour, well-known even to Madonna and George Harrison. Yet the lush and succulent singing was far from genuine. Where and what was the real music behind these adaptations?

In 1987 I arrived in Sofia, Bulgaria to play the blues and lecture on the minimalist music scene which swept away New York in the late 70’s, all very new to Bulgarians. Their government put me up in the swanky Grand Hotel, facing the parliament with the Ivan Nevsky cathedral just behind. Its doorman had a sailors cap and walrus mustache and at night some ladies would ask if I wanted “tak see”. Rising at six a.m. when all was still, the calm allowed notable buildings to shed their daily role as scenery and take on imposing airs:

On breaks between lectures at the National Conservatory it was tempting to venture beyond the center and dive into outlying neighborhoods. Heading downtown on the main street one passed by a prominent mosque:

and a side street led to a synagogue tacitly wedged in where its caretakers spoke the Ladino from their origins as Jewish citizens who left Spain after 1492. Its dome and façade are hinted at on the left:

Arriving at the farmers’ market I checked to see what was still available in late February:

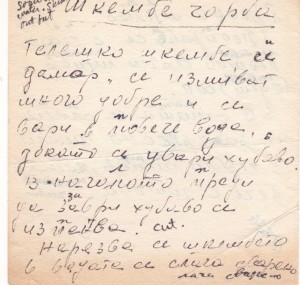

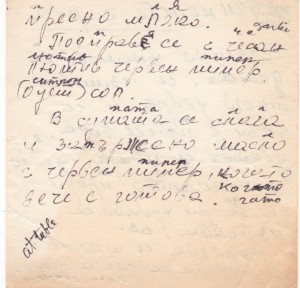

At the market’s edge sat a khancho-mekhana (tavern) serving the restorative shkembe chorba (tripe soup) that resolved debilitating hangovers.

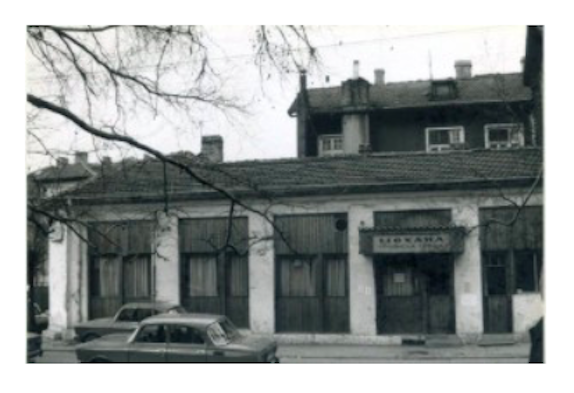

As everyone was heavily smoking, it was impossible to breathe so I wandered off to a sleepy Tsar Simeon street, closely watched by a feline operative:

It was a step into time travel, Ottoman splendor, and one solitary man returning from work looked aghast at a foreigner snapping pictures of many decrepit but intriguing homes.

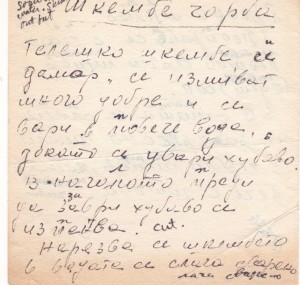

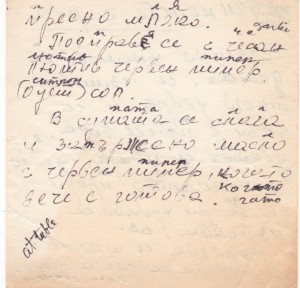

Once we found that German could get us through a conversation he advised caution as this suspicious activity might imply a later use for negative propaganda. My desire for tripe soup hadn’t abated after the khancho and we began discussing this new-found delicacy. Invited to his nearby home for a drink, he kindly wrote out his very own way of preparing the broth.

The same kindness was returned by students and teachers at the Conservatory who reciprocated with a surprise for their first American, one lusting after their folk music. At days’ end a group of us set out for Bistritsa. a mountain village overlooking Sofia. Accompanying us was a folklorist mischievously smiling through his pointed oriental goatee, informing us that seven elderly women would receive us in their village’s community center where the dinner table had been set. Tiny bird-like Baba Menka, over eighty and resembling an ancient Roman matron depicted on frescoes. entered the rec-room with a home-made bread wider than her heaviest singing partner’s waist. At the table the Babas (grannies) still wore their blue day work smocks and demonstrated to their foreign visitor the right way to rub bread with chubritsa, a powdered blend of cayenne, fenugreek, wild thyme and summer savory which finds its way everywhere in Bulgarian cuisine. It later occurred to me that it resembled Georgian khmeli-tsuneli a spice blend, both possibly drawing on Central Asian traditions from where the Proto-Bulgars also originated.

With it came tangy feta cheese shredded over tomato and cucumber salad, washed down with Rakia, their own potent anisette liqueur packed with more than 60% alcohol. As our heads started spinning, the Babas excused themselves, reappearing minutes later in traditional village costumes, singing antiphonally and dancing in a circle.

It was soon clear why Orpheus was said to have come from Bulgaria. Their voices dovetailed each other above a droning tone. Such full-bodied and powerful harmonies were only hinted at by the Mysterious Voices, who now seemed too polished and sleek, their sparklingly clear tones caged within diluted rhythms. The Bistritsa Babas sang the way Aristotle described the Phrygian modal scale, which the Babas often used; “it makes men enthusiastic.”

Archaic polyphony

What was behind this, the authentic Bulgarian singing?

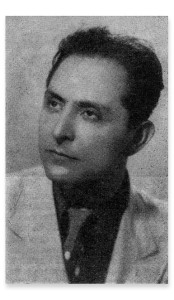

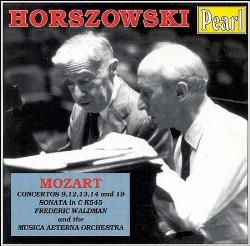

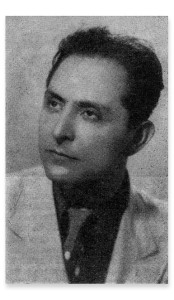

The mystery was probed the next day when I met Dr. Stoijan Djudjev, then 86 years old.

The Bartók of Bulgarian folk music, he had devoted his life to its singing, instruments and their dances. “I studied linguistics in Paris during the 20’s. If modern Bulgarian has traces of ancient Greek languages, then why shouldn’t our folk music have retained it as well? This was my method for studying our music.” With all the shortages. it was hard to find LPs in Sofia of the real folk music, but some four or five were rounded up, including one with the old ladies of Bistritsa. Soon the Mystere des voix Bulgares was released in Switzerland and the US.

Summer of 1991: While the Bulgarian TV Ensemble and Balkana are touring abroad, thousands of villages throughout Bulgaria selected their best singers, musicians and dancers for their descent on a little mountain village east of Sofia: Koprivshtitsa. Every five years, this Balkan Woodstock explodes for three days on the second weekend of August. Baba Menka died a few years ago: worried over the Babas becoming a vanishing species, I grabbed a flight which stopped in Vienna for the Sofia connection. At the departure gate sat a man busily engaged in looking inconspicuous. Small headed, rat-faced, he wore dark: sunglasses, headphones, a sharply cut polyester suit, while a walk man rested on his locked briefcase as a prop: Bulgarian diplomatic ingenuity personified. Nearby a dozen freshly scrubbed blonde boys and girls wore “Elder” and “Sister” nametags in Cyrillic: Mormons from Utah! “We’re going over for a two year mission.” One Elder boasted of their grueling language seminar: “It was rough going, but we had Bulgarian classes 14 hours a day, 6 days a week for two months.” Maybe they needed three months as most couldn’t even begin to pronounce Koprivshtitsa which sounded like something you’d follow with gesundheit, but such meetings are normal now when heading towards the East. On any given trip chances are that you’ll rub shoulders with Bible salesmen or missionaries itching to hawk God’s aspirin to soothe the hangover when Atheism was dropped as the obligatory religion.

Four years earlier, the streets of Sofia were quiet. Those brave enough to speak openly looked over their shoulders while whispering about their run-ins with the secret police, schemes to marry foreigners or defect. The Communist Party building had been torched last winter. Like Lenin in Moscow, the embalmed corpse of their hero Dimitrov resided in a mausoleum across from the royal palace on a yellow brick road which runs along downtown Sofia. Now Dimitrov has joined contented worms underground while his old refrigerator is splattered with graffiti, the goosestepping honor guard gone. People seemed nervous but animated; makeshift stands of books, jewelry, stamps and objects were everywhere. One saw the Indian erotic manual, the Kama Sutra, being sold in a Bulgarian translation. Behind a roped-off area in a park, a group of homeless Bulgarians were on a hunger strike. “Break dance” was spray-painted onto a nearby wall. Many once-nerdy students now seemed to be trying their best to dress punk or hippie. New icons hung on the walls in a friend’s kid sister’s bedroom: Jim Morrison and Pink Floyd.

Koprivshtitsa was slowly coming to life as people began flocking to this village.

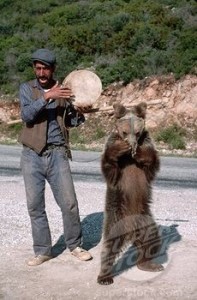

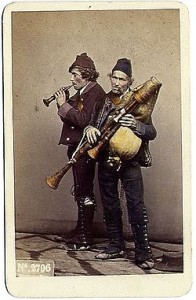

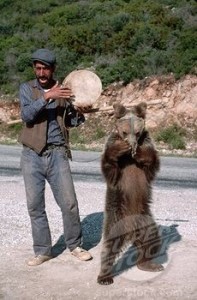

The first musician was sighted: a dark Gypsy led his chained muzzled bear across a stone bridge into the town’s square: the bear stood at full height on his hind legs whenever his mustachioed master played on the gadulka, a thin Balkan fiddle which hung on his waist. Any pleasure in watching the bear dance vanished when realizing the measures taken by the Gypsy to train his better half. The village houses were a few hundred years old, having massive barn doors leading to courtyards surrounded by high stone walls. These anti-Turk measures were once a necessity: the Ottomans held Bulgaria for 500 years and enjoyed collecting outrageously high taxes while arranging one-way trips to Istanbul for the town’s prettiest daughters to enter harem servitude. The festival is more like a fair, a gathering for Bulgarians with some foreigners straying about: above the town on the mountain-top eight stages go non-stop for twelve hours from Friday to Sunday. It all started in the 1940’s when two soldiers who began searching villages for old music and rituals wanted to assemble their finds. Many ancient Bulgarian traditions were being gradually destroyed when a heavy migration to the cities began in the 1950’s. While Bulgarian religion had always allowed pagan rites to continue for centuries by incorporating them, a tiny dose of sterile city life was enough to snuff them out since country living was less gloomy.

The government, always ready to manipulate nationalistic tendencies and distract the people from their oppression, gave the go-ahead for song festivals in the 1960’s, deeming them politically correct. Villagers once again took up their bagpipes and gadulkas while the Babas slipped on embroidered two-hundred year old costumes to sing out their village’s soul. Folklorists chose Koprivshtitsa in 196 5 for their first national happening, and since 1971 it has followed a five-year plan.

It takes a good twenty minute uphill hike on the town’s stone streets to reach a paved road leading past grazing goats and horses into the fir and pine-ringed meadows with its scattered stages and narrow paths. Vendors set up tents or operated out of vans and East-block autos. Behind the tents are wooden sheds housing the famed Turkish toilets, where you plant yourself firmly on stone footprints and aim. The smell of grilling shish-kebab mixed with blaring cassettes of Yugoslavian pop, the Balkan version of Nashville which truck drivers feed on during their long hauls. In the roving crowd were Gypsies leading their begging bears, flocks of costumed Babas, folk-dance fanatics, Westerners – easily spotted in T -shirts with Cyrillic writing, Bulgarians -in Western T -shirts, mummers lugging their three-foot high animal masks with huge cowbells strapped onto their waists: 17,000 performers, 5,000 spectators.

There were problems this year. The government is now led by the opposition, yet the deposed dictator’s bureaucrats are still entrenched. No money was appropriated for the group of experts and folklorists who have planned the festival since its inception, and the little that was coughed up at the last minute couldn’t pay for the most famous groups. Villagers from the Yambol region didn’t seem to care, as they sent over a thousand musicians and occupied a stage throughout the event. The festival started up at nine a.m Friday. Each village was given a few minutes to sing two or three pieces. Eight ladies from the mountains near Dimitrovgrad wearing hortensia in the hair belted out their raw harmonies and whoops. They faced the crowd with hands on hips, a peasant’s stance, in two groups. I followed them as they left the stage to sit away from the blaring sun. Their costumes were bewilderingly ornate, hand embroidered in heavy wool: “This was my great grandmother’s- two hundred years old.” One Baba sized me up right away as a foreigner: ‘You’re from America?l” she smiled. “My husband left for America thirty-two years ago when I was pregnant. I tried to have the Red Cross search for him, but nothing ever came of it.” She sighed, but smilingly invited me to her village.

Koukeri: Mummers

A shamanic ritual with mummers known as Koukeri, said to have its origins in the Dionysiac rites, was revving up on the next stage. While a bagpiper bleated away, his drummer thundered out eleven beat rhythms on his waist-drum. The village’s men wore painted masks with protruding phallic noses, leading a wooden horse whose mouth gaped open and snapped shut. It was the Hunt of the Spirit, which represented the movement of the world. Circling and dancing around the beast, the sound of their cowbells nearly obliterated the music. The dance became more frenzied as they stomped in time to the drummer and began raining heavy blows with cut staffs on their neighbor’s padded backs.

Many villagers went barefoot in order to save their shoes for the performance. A group of mummers from Bourgas, by the Black Sea, readied themselves. Dressed in black vests, cowbells, wool legging on their shins, they mounted three foot high glittering headdresses and adjusted fake wool beards. Some of the masks were made from the heads of animals once slaughtered for village feasts, exaggerated in their grotesqueness by being mounted with fur and enormous horns. A goat mask symbolizing Satan: the Mummers encircled the Devil, rendering him powerless with their White

Soon after a helicopter descended and out onto the television’s stage stepped Zhelo Zhelev the Prime Minister. The crowd cheered wildly at his arrival as he is from the opposition party. Zhelev began by addressing them as “Brothers and sisters … “. Afterwards Dimo Dimov, the new Minister of Culture came up to the mike with a written-out speech which he drily delivered. Dimov, a top notch violinist himself, prefers to spend government money on classical music and is not very concerned with folk music. Many are worried about his attitude, as it threatens the survival of Koprivshtitsa and other festivals.

Noise came from the far-off Yambol stage where their mummers were off on a demon hunt, led by a rider on a wooden horse who was whipped constantly on its rump. A ‘bear’ came on the stage, symbolizing the forces of health, proved that the hunt succeeded by removing the demons away from a mother (a man dressed as a woman) holding her sick child. Afterwards, an unending stream of singers and instrumentalists took hold of most stages, with less mummery going on.

The sun sank behind a far-off mountain and we headed down for another ritual: pleading with the town hotel’s headwaiter for a table and a meal. He was very sorry, but no tables were available. After keeping us in suspense for awhile, he did us a great favor by finding one. While we ate, several neighboring tables remianed empty. The bill seemed reasonable but shocked our Bulgarian friends; as there is no menu nor prices posted, you take what you get and pay what they demand. While chewing on kebab, a folklorist came by with the news that tonight the Yambol groups were going to dance and play all over the streets. Down the river’s road away from the center of town, the performers were put up in tents cordoned off in a muddy field segregated by their regions. “They don’t mix much, because one district wouldn’t know the dances or songs from another.” We searched in vain for the Yambolers. Sounds mysteriously emanated: ahead in a large tent packed with Babas who, lying side by side on their backs, sang one piece after another in the dark. Back on the road, we hit a crowd drinking beer, dancing wildly and singing all night long. If any doubt lingered as to the festival being a staged spectacle by people mechanically aping their ancestors way of life, their joyously frantic dancing and the Babas soaring above their tent in song hit me with the importance and meaning it has for them. They rarely have the chance to leave their villages, and this trip to show their most cherished possession – their music – to everyone is a great event in their lives. All throughout the festival, most of the listeners at each stage were the performers themselves.

On Saturday as the crowd swelled even further. an unimaginable apparition materialized: Turkish Women were openly strolling in harem pants with kerchiefed heads. Until the opposition took over, it was illegal to dress, speak or live as Turks. The secret police kept tabs on the few Mosques which were allowed to function. In the 1980’s the government sent goon squads to villages having Turkish minorities. The Turks were lined up before tables in the main squares where officials doled out new Bulgarian names: those refusing to abandon their Turkish names were shot dead on the spot. Nowt hey have their own newspaper. At this festival of Bulgarian-only music, a few dozen Turks were sprawled out on a slope behind a kebab tent, dancing away to their hypnotic rhythms while thrusting their hips and bellies at one another holding their outstretched arms high in the air, the women wriggling their huge breasts at their Elvises.

It was a big comedown to cross paths with hairy-legged vegetarians from the US who perfectly copy the choral singing. Many of them are fluent in Bulgarian, as were the japanese members of Koga, a Tokyo-based Bulgarian dance association, who content themselves with knowing and reveling in the many dances. These Bostonian wanna-be babas sing faithful renditions, but as pseudo-Bulgarians their tone is nowhere as full or convincing as the Babas. Chalk it up to their city-bred ideologies or never having needed to kill chickens for dinner, it showed the cult-like following which any great art inevitably draws.

One of the main events came on Sunday morning. Minus Baba Menka, the Bistritsa singers stepped out and proved themselves to be one of the festival’s high points. They sang for only fifteen minutes yet left everyone Koprivshtitsa began winding down as the performers headed back home on a caravan of government buses. The train to Sofia was crowded: an adjacent row of seats had a big card game going. One of the players left his bottle of moonshine on the floor and it overturned, filling the car with a pungent herbal fragrance. Ladies were dragging bags filled with preserves and vegetables back to Sofia from the garden plots at their country bungalows and dachas. The city seemed hectic after Koprivshtitsa but a bit soulless. I longed for the three day immersion which ended too soon, the ceremonies in which roasted goat meat was offered by ravishing young women who sat sewing, the mummers, and above all, the Babas, who seemed to have the best sense of what really mattered in life and could size up whatever happened before their shrewd eyes. Their honest work and living with their customs allowed them to see the West as but a source of both good and bad, unlike many Bulgarians who delude themselves into believing that all their problems will be solved by Western money and technology but not from within.

I grabbed a taxi and reached Bistritsa in twenty minutes. Little private hotels now dot the hills along the Vitusha mountains. In the community center, just as it was four years ago, the Babas come in every night after a hard day of working to rehearse. Foreign guests are no longer a novelty: this night several English singers came to videotape their practice session and sing for them. Unlike four years ago, the old ladies were now joined by young women from the village who were foxy as hell and eager for some disco, yet loving their music as much as any other. Standing side by side with the old ladies they are slowly absorbing the Babas’ timeless art and a humanity which the last forty years of oppression failed to degrade.

While some of Koprivshtitsa is pure but good theater, it is comforting to see that there are still some Babas to go around and new ones in the making.

And the mystery? Composers unable to write freely due to the regime’s prohibition of unofficial musical styles still had to produce in order to get paid: they arranged folksongs that the Koutev Ensemble and others introduced and the rest is history. But at the last moment of the 1991 festival, an ethnomusicologist explained that the National Academy of Sciences housed thousands of pre-war field recordings and most were deteriorating. It still needs to be addressed before Bulgaria loses even more of its remarkable heritage.

–©Allan Evans 1991, revised 2014