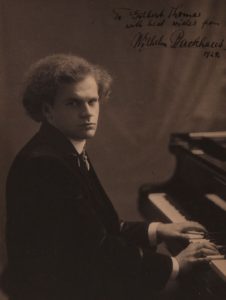

When one overlooks the norm of current performances to seek Bartók himself performing his own works, contact with his unique approach will alter your judgment of all other interpreters. Disappointed by being bested by the younger Wilhelm Backhaus

at a piano competition, the world was luckier for the lack of a stellar career of touring would have limited the time he spent in collecting folk music, a bold and unprecedented crossing of class lines that led him to create a musical language of his own.

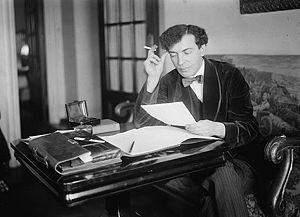

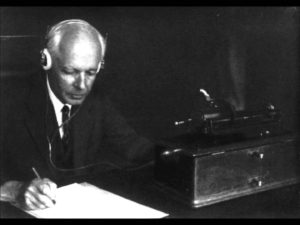

Bartók transcribing a field recording cylinder.

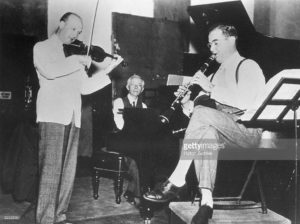

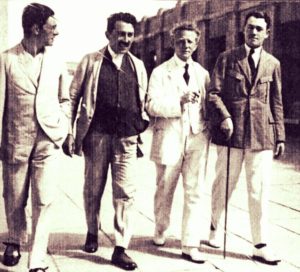

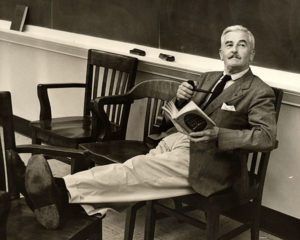

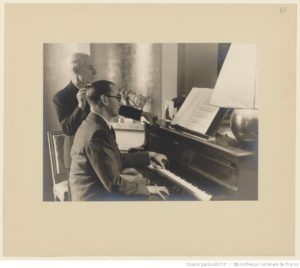

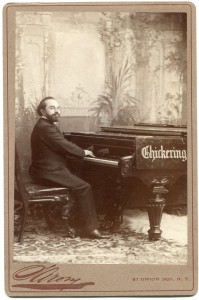

Bartók taught piano, not composition, but explained music from a creator’s perspective. Even live performances in works by other composers offer details, extremely crucial ones, that will open up a composition’s inner life. Most people will not associate Bartók with Beethoven, aside from a previous dimly-restored performance of the Kreutzer Sonata (Op. 47) with his sonata partner Joseph Szigeti (seen here with clarinetist Benny Goodman while recording Bartók’s Contrasts.)

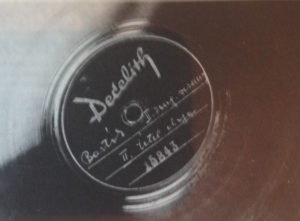

and a fragment preserved on an x-ray plate used to record his Budapest radio broadcasts on demand by poetess Sophie Török, an admirer whose personal intervention rescued several hours of his legacy.

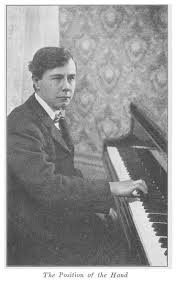

When I first heard Irén Marik playing Liszt on a discarded vinyl lacking any cover or info, a vision arose of a young lady seated with impeccably correct posture at the piano,

Bartók standing nearby, advising. After a rare discovery that led to tracing her in the California desert she verified that Bartók had been her teacher. “Did you study his music with him?” “I first played something of his and he said ‘I see you understand it so let’s go on to Beethoven and Mozart.'” Marik was the closest to the composer’s own playing but what did he convey in other composers?

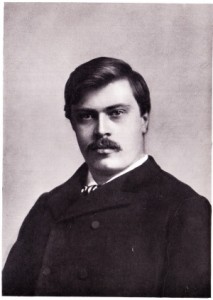

A clue was detected in the opening of Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata. The violin’s first phrase has arpeggiated chords that cover several strings. One can play then in a constricted manner within their allotted time or spread them out. An insignificant detail? Two recordings from the 1920s to examine: Isolde Menges with Liszt-pupil Arthur de Greef at the piano, followed by Jacques Thibaud with pianist Alfred Cortot:

Both violinists phrase a taut opening, matched by pianists that keep their hands together. Bartók and Szigeti are different:

Many scholars and the puritanic would dislike the way Bartók breaks the chords, written as solid sounds by Beethoven himself. Yet by subtly copying Szigeti’s arpeggiated attacks we are exposed to an irregularity within a pattern, the basis of chaos theory. Dr. Henry Burnett uncovered similar actions that involved opening gambits through chromatic notes that comprise a new theory of tonality spanning from the late Renaissance to early Schoenberg, a penetration that leaves Schenker in the shade. Beethoven will unfold a rhythmic interplay throughout his sonata that developed out of what is considered to be incorrect, a trivial gesture. That integral detail has a subliminal DNA role that comes to light elsewhere, especially in this later passage that otherwise sounds like a flippant rhythmic interlude unless one is aware of its origins. Beethoven augments and shortens the arpeggi into rhythmic gestures that evoke origins in the piece’s opening (again Szigeti and Bartók), a way to ensure identity and continuity:

What kind of Bach did Marik from Bartók? His performance of the Fifth Partita in G survives on x-ray plate decelith discs with some gaps occurring whenever a new three-minute side was mounted (the record store owner who provided this service eventually bought a second machine to overlap while changing discs.)

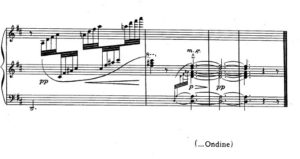

The opening Preambulum is complete, newly restored:

Bartók kept company with Robert and Etelka, familiars of Brahms. How could their connections with this recently deceased composer not have been taken up by Bartók? An x-ray contains has Bartók’s performance of the Capriccio in B minor, Op. 76, no. 2:

With his wife Ditta Pasztory, a piano duo started up, around the time he composed his Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion. They continued as long as his health endured, playing contemporary works such as Colin McPhee’s Balinese Ceremonial Music.

Those familiar with his Mikrokosmos will recall From the Isle of Bali. I asked Bartók’s son Peter, author of a splendid family memoir, if his father had Balinese recordings from 1928, the only pre-war session. “He had the Music of the Orient set [1930],” referred to by Percy Grainger as his introduction to gamelan. They played Debussy’s En blanc et noir which adds to our experience of Bartók and Debussy as he and Szigeti included the Violin Sonata in their recital. Part of the first movement is heard. One can pick up many traces of Javanese music in Debussy.

The entire first movement of the Beethoven Kreutzer sonata should be listened to, know that you have a better grasp of Bartók’s pianism and creator’s mindset.

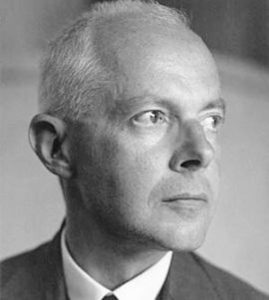

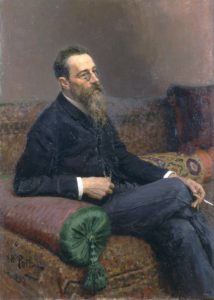

Second to Bartók’s pioneering exploration of folk music was Zoltan Kodaly.

Bartók’s first studio recordings comprised folk-song settings of Kodaly’s and his own. Two examples by Kodaly are sung by the contralto Maria Basilides accompanied by Bartók

A rossz feleség (The Heartless Wife) opens as a dirge with a child urging her mother to come home as the father is dying, only to be put off.

A children’s song Kitrákotty mese (Cockricoo) concludes with the tale of someone heading to a fair to buy animals with half a coin, imitating their unique sounds:

The unending charm and sparkle in Bartók’s playing resonates the love and insights gained from leaving society to seek music from the peasants, a period he considered to have been the happiest days of his life.

–Allan Evans ©2016

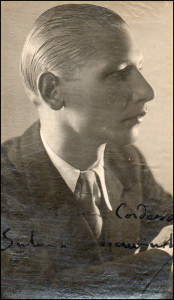

![Magaloff-Nikita-09[1986]](https://arbiterrecords.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Magaloff-Nikita-091986-300x229.jpg)