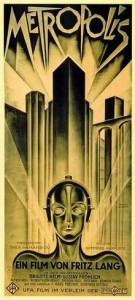

What on earth does the Frenchman Debussy have to do with Asian music? It sure effected his music and once you hear what lies there, it will change your own listening! The barrier begins when most pianists struggle to drag their familiar Debussy into his late works, where he reinvented himself in a Modernism leaning towards Mondrian rather than remaining shut into the sonic Monet he was made to represent. Debussy’s old clothes no longer fit and their efforts fall flat.

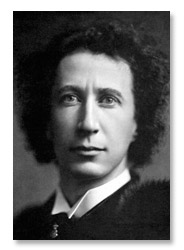

Let’s sample a bona-fide critically-acclaimed Debussy expert, Walter Gieseking,

playing an excerpt from Etude no.7. The studio mike is usually placed at a distance to reduce the snorting from his adenoids, giving the sound more Impressionism as his producers sought to shape and sell it while lessening his nose tones:

It’s played like an Etude, a gymnastic feat deftly tamed. But Debussy’s underground use of harmony and motivic narrative was left lying unsuspected and ignored. Yvonne Loriod, a couple of decades younger, married Messiaen

and knew damn well where the late Debussy led and could look back and demonstrate his innovations that the limited Gieseking didn’t grasp.

One outside culture that unexpectedly hit Debussy was his encounter with Indonesian music at a Paris Exposition. We can only guess which gamelan genre he heard but I offer this alluring private gamelan playing Babar Layar, owned by a Chinese merchant in Java who allowed them to be recorded around 1928 by visiting Germans. The European engineers left out its deep bass gongs so use your imagination to fill them in:

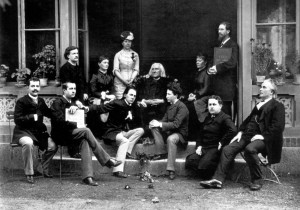

Debussy spent time with Stravinsky who came to Paris for his new works presented by the Ballets Russes with Nijinsky and Diaghilev. At Debussy’s they played through the Rite of Spring on two pianos and became well acquainted musically and socially. One striking detail in this shot of the emergent Stravinsky with a moribund Debussy is the artwork in Debussy’s apartment: Japanese prints.

Just as Debussy’s idea of Asian music is presented as if emanating from a Renoir parlor, we hear Pagodes given in the way a Parisian would browse postcards. Gieseking was born in Lyon, France and grew up bi-lingual. He loved collecting butterflies more than playing the piano but here in 1938 he is sensitive to its expressive shapes:

Unlike Gieseking, the German-trained Percy Grainger collected folk music, trekking to Nordic villages, covering the Celtic cultures of the British Isles.

He and Béla Bartók owned copies of Music of the Orient, a pioneering set of discs spanning from Japan to Persia.

Grainger gave an evening in Austin, Texas’s university, playing solo, with wind ensemble and addressing listeners. Obsessed with Pagodes, he once arranged the piece for multiple pianos and percussion. Here are some remarks by Grainger in a thick Australian accent:

Now hear Grainger keeping his word by pedaling heavily to keep the gong tones ringing. What you’ll experience is a boundary between Western and Asian music being shattered as a new form emerges. Grainger was twenty-two years younger than Debussy and thirteen years older than Gieseking:

Debussy Pagodes by Grainger, Texas 1948

While Debussy was dying from cancer and hardly able to compose, he received visits from an Indian guest:

Inayat Khan, a Sufi philosopher, brought a veena along for his European lecture tour. He met often with Debussy, playing the instrument and singing. Debussy asked to borrow the veena while Khan covered the continent. Khan may have given Debussy some lessons and perhaps he picked it up on occasion but died before Khan’s return and the instrument was lost. A greater loss was the style it could have influenced, but traces of Asia in Debussy still emerge, one as recently as 2011.

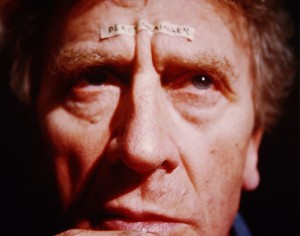

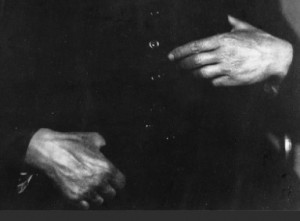

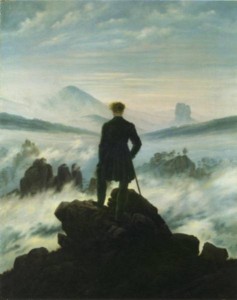

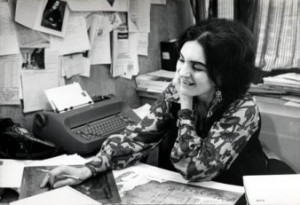

On a visit to violinist Roman Totenberg, who at age 101 still teaches and can recall plenty from ninety-four years of music-making, I played for him a recording of his early idol and mentor, Bronislaw Huberman. It was Brahms’s violin concerto and I snapped a photo of his enrapt listening, putting aside body and environs to enter deeply into the sounds, which amazed him now as they did then:

On an earlier visit, I searched through his archives at his request and found many hours of concert recordings he had gathered throughout some sixty years. One tape from 1960 had Debussy’s violin and piano sonata. It was a difficult piece even for most renowned players to capture as violinists high and mighty lapsed into scales and occasional maudlin phrasing but seemed incomplete. Totenberg’s had a grasp that eluded the others. I had to ask him what was behind it all:

“When I came to Paris in 1933 I studied with Enesco and was eager to learn the Debussy sonata. After a year there I noticed that no one had ever programmed it in concert.”

Was it too difficult musically, or ignored for being passé?

“So I found two pupils of Debussy, one was Marcel Ciampi, and they coached me in it. Ciampi mentioned its being influenced by Asian music.”

And so it was, and I published it shortly after its discovery.

Keeping Grainger and the gamelan in mind, hear Roman Totenberg in an excerpt. A deep listening occurs as he plays:

Debussy, from The Art of Roman Totenberg Arbiter CD 159

I apologize (not really) for this lengthy post but this is what flashes through my mind when these people are mentioned and thus wished to spell it out for you in real time. . .

–©Allan Evans